— Preparing for the Psychological Impact of Virtual Selves and Memories

“Life after death is real in this digital era.”

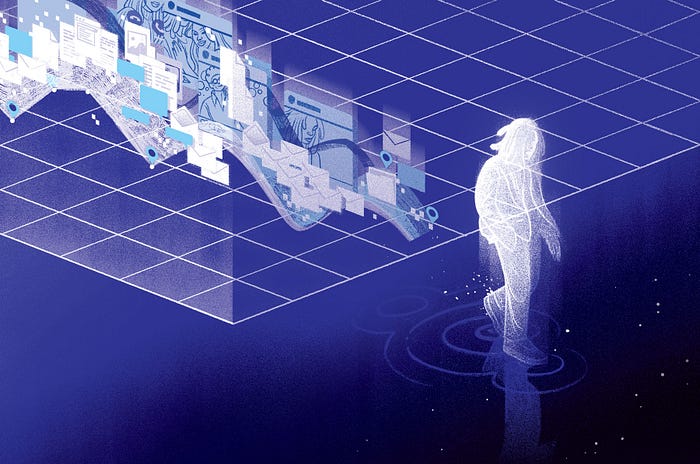

Welcome to the age of the digital afterlife, when the lines between the real and virtual worlds blur, giving rise to the notion of virtual identities and memories. As technology advances, the concept of digital immortality becomes more apparent, compelling us to investigate the psychological consequences of existing beyond our physical life. This article delves into our emotional commitment to our virtual selves, how we cope with grief and loss in the digital domain, and the ethical concerns surrounding digital immortality.

Virtual Immortality: A New Existential Paradigm

Consider a world in which our mind exceeds the confines of our physical body. We can attain virtual immortality in the domain of the digital afterlife, allowing our ideas, memories, and personalities to live on after death. This virtual life is made possible by breakthrough artificial intelligence and virtual reality technologies that digitally replicate our essence. However, the idea of immortality brings with it significant ethical quandaries that call into question our notion of life, death, and what it is to be human.

The Psychological Consequences of Digital Afterlife

The concept of surviving in a digital form raises concerns about the emotional commitment we establish to our virtual identities and memories. We form profound emotional connections with these representations as we devote time and attention to creating our digital identities. When faced with digital loss, such as the deactivation of a virtual self or the erasure of digital memories, we feel a distinct sort of grieving that necessitates the development of new coping strategies.

The Role of Technology in Memory Preservation

Artificial intelligence and virtual reality advancements have enabled the creation of lifelike virtual representations of ourselves as well as the digital preservation of cherished memories. These technologies not only allow us to review our prior experiences, but they also allow future generations to engage with their predecessors’ digital legacies. However, the advantages of digitally storing memories are accompanied by possible downsides, such as the change or manipulation of these memories.

Embracing Digital Estate Planning

The notion of estate planning has expanded beyond physical assets to embrace digital assets in the age of the digital afterlife. Proper digital estate planning entails organizing and managing one’s virtual identities, social media profiles, and digital memories in order to ensure their smooth transfer to trusted others after our death. By taking control of our digital legacy, we can make a significant difference in the lives of those we care about.

Security and Privacy Concerns

As we spend more of ourselves in the digital environment, the need to protect our virtual selves and memories becomes increasingly important. Concerns about privacy and security develop as a result of the possibility of unauthorized access to sensitive data and the danger of identity theft. To prevent exploitation and misuse of our virtual existence, we must strike a balance between sharing our digital lives and preserving our digital identities.

Support Groups and Virtual Therapies

Virtual worlds are becoming significant instruments in therapeutic and emotional support, not merely as a form of entertainment. Virtual treatments give a secure area for people to examine their emotions and tackle unsolved concerns. Furthermore, virtual support groups provide consolation and solace to people who have experienced digital loss by allowing them to connect with others who understand their specific challenges.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

As the notion of a digital afterlife gets traction, it becomes critical to build updated legal frameworks to address concerns such as digital estate planning, virtual self-inheritance, and digital memory ownership. Furthermore, ethical issues necessitate a more in-depth examination of how we handle the digital afterlife responsibly while honoring individuals’ preferences and liberty in both life and death.

Cultural Views on Digital Afterlife

The digital afterlife also calls into question our traditional assumptions about life after death. Various civilizations have different ideas about what happens to the soul once the physical body dies. We are witnessing a development of spiritual practices that integrate traditions with the digital era as technology and spirituality meet. Accepting these cultural ideas offers up new doors for spiritual development and understanding.

The Effect on Social Dynamics and Relationships

As our virtual personas grow more and more ingrained in our lives, they unavoidably have an impact on our relationships and social interactions. Nurturing relationships with our virtual selves, participating in virtual groups, and establishing connections in the digital domain all influence how we interact and relate with people. It also calls into question the sincerity and depth of these connections when contrasted to face-to-face conversations.

Grief and Healing in the Digital Age

“The people you shared those times with, the times you lived through; nothing brings it all back to life like an old mix tape.” It is more effective than genuine brain tissue at storing memories. Every mix tape has a tale to tell. When you put them all together, they may tell the tale of a life.”

Grieving takes on a new level in the domain of the digital afterlife. When faced with the loss of a virtual self or a loved one’s digital memories, individuals suffer a distinct sort of sorrow that necessitates creative ways of healing and closure. Virtual monuments and digital places for memory provide comfort to people looking for ways to respect and love their virtual relationships.

Mindfulness and Digital Detoxification

Living in an era where the digital afterlife is a reality necessitates balancing our physical and virtual selves. Mindfulness and digital cleansing assist us to be present and avoid getting excessively tied to our digital selves. We may maintain a healthy relationship with technology and focus on developing significant real-life experiences by withdrawing from the virtual world on a regular basis.

Identity and Self-Concept Development

The emergence of virtual selves calls into question established ideas about identity and self-concept. Individuals have the option to explore different facets of themselves in the digital afterlife, adopting a more fluid and dynamic sense of who they are. This identity growth opens the door to deeper self-acceptance and an appreciation of human complexity.

Preservation of Educational and Historical Values

The digital afterlife expands educational and historical preservation opportunities. Virtual selves may be used as dynamic and engaging instructional tools, allowing students to connect in a profoundly immersive way with historical personalities and events. Furthermore, digitally archiving historical personalities and their memories guarantees that their contributions to society are never forgotten, establishing a stronger feeling of connection with the past.

Future Planning: Embracing Change

As technology advances, so will the notion of a digital afterlife. In order to prepare for the future, we must welcome change with an open mind, cultivate continual debate, and explore the potential of the digital environment. We can design a future where virtual selves and memories improve our lives without overshadowing the beauty of the actual world if we approach the digital afterlife properly and ethically.

Final Thoughts

The digital afterlife represents a fascinating and difficult frontier of human existence, testing our understanding of identity, relationships, and the essence of life and death. As technology advances, the psychological influence of virtual selves and memories will only become more prominent. However, with mindfulness, empathy, and intentional preparation, we can traverse the digital domain with wisdom and compassion, ensuring that the virtual world supports rather than overpowers the depth of our real-life experiences.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!