—So I Wear Her Perfume Instead

By Matt Ortile

I woke up terrified last Friday. Or was it last Thursday? Maybe yesterday. Today?

Each day bleeds into the next when in social isolation to hinder the spread of the novel coronavirus. This pandemic brings with it an acrid kind of despair, infiltrating every hour of our lives, every call we make and text we send. It’s this nauseating smog in my home, where I’ve had the privilege of working remotely, shut away from the world.

One morning, the miasma began to suffocate me. Reports said that nearly 4.4 million people were newly jobless in the U.S., some of my friends among them. Dreadful images of overcrowded hospitals appeared all over the news, while the number of those who tested positive for the virus only continued to rise. It was hitting me that people are dying because a president too concerned about his re-election chances did not acknowledge or prepare for the oncoming global health crisis.

I couldn’t breathe. I opened my windows and watched my quiet Brooklyn street. I went to my dresser. Deeply stressed, I did what I’d always done: I put on some perfume.

It’s my mother’s old favorite, a scent called “Thé Vert,” French for green tea. I bought the bottle during my first summer in New York. Overwhelmed by my magazine internship and yearning for a whiff of home, I went to a L’Occitane near Lincoln Center and sprayed the fragrance on my wrist. It’s a clean scent, floral yet piercing—Camellia sinensis with talons. My pulse steadied. My mind went from cloudy to clear. A single spritz was a vivifying hit.

A salesperson came over, eager to assure me Thé Vert was unisex. I didn’t care either way. I marched to the register with 750 milliliters of the stuff and emptied my wallet onto the counter. That evening, I ate dinner street-side (a five-dollar lamb and rice plate), as the oily halal cart aromas mingled with my new perfume.

It’s been a good investment. That was eight years ago and I still have that same bottle to this day. Some of my fragrances have turned bad over time, but Thé Vert, I think, hasn’t changed much. The green tea is still there, though now it smells peppery when it tickles my nose. Ultimately, its effect is the same: Wearing it, I inhale botanical grit, my mother’s eternal fortitude. And then, whatever anxiety I can release, I get to exhale.

L’Occitane launched Thé Vert in 1999. Bitter orange is the primary top note; the middle notes are green tea and jasmine; nutmeg, cedar, and thyme make up the base. Some reviews on the perfume site Fragrantica associate it with “a happy summer day” or “a picnic at the park.” But when I smell it, I conjure other images entirely.

To me, Thé Vert is five o’clock in the smoggy Manila morning. It’s my mother in her blazer and pencil skirt, applying a full face of makeup in the two-hour traffic jam, dropping me off at school en route to work. Thé Vert is me sobbing into my mother’s collarbone, hurt and confused by men in my family who told me to “man up.” It’s her consoling embrace, her reminders that this storm will pass once we beach upon more welcoming shores.

Thé Vert is my mother in her bedroom in Las Vegas, crying on the phone to my stepfather in the Philippines, separated from her beloved. It’s me hugging her, reminding her that we have each other as we restart our lives in this strange new country. It’s us finding solace in beautiful, simple things—in shared meals, in French perfumes, in our mutual trust and friendship.

As time wore on, my mother wore her perfume less and less, until she finally stopped. L’Occitane discontinued Thé Vert in 2013, a year after I first bought it. They replaced it with the remixed Thé Vert & Bigarade. On Fragrantica, a reviewer called the new formula “bitter and sickly,” and preferred the original Thé Vert because it was “penetrating” and “sharp.”

My mother was similar, someone who cut her own path—for herself in the Philippines; for us both in the United States. That’s the woman I try to channel whenever I put on Thé Vert. I imagine walking through a cloud of atomized courage, borrowing my mother’s conviction, her grace. The bloom of it on my skin tells me that, against all odds, all will be well.

“I’m wearing your perfume today,” I told my mother recently. (This Sunday? Last Tuesday morning?)

Daytime in Brooklyn meant nighttime in Manila, where she and my stepfather now live together. Their self-isolation began around the same time as mine. I could hear the television in their townhouse. They were watching a press briefing live on CNN.

She doesn’t wear fragrances anymore, she said, “so it’s your perfume now, anak.”

I said that it still reminds me of her. It comforts me, makes bearable the fact that I can’t be by her side in the middle of what, on the worst days, feels like the end of the world. I wish I could see you, I told her. She smiled; I could sense it over the phone.

“It’s safer that you’re not here,” she said. “But I miss you too.”

I was supposed to visit my family this spring. But between my work schedule and preparing for the publication of my book this summer, I never got around to buying a plane ticket. This procrastination did me a favor, sort of. When New York governor Andrew Cuomo declared a state of emergency on March 7, my mother told me—jokingly, I think—that God had willed my indolence.

Just as well, we agreed. Flying from the U.S. to the Philippines would have meant going through multiple international gateways, potentially contracting the coronavirus along the way, and possibly passing it on to my mother and stepfather. They’re getting on a bit—she’s in her 60s; he’s in his 70s—and the Center for Disease Control states that older adults are at higher risk for severe illnesses from COVID-19. Also, my mother is immunocompromised. This is because she has cancer.

Again, I should say. My mother was initially diagnosed with breast cancer in 2015. Treatment put her into remission by the summer of 2016; by the fall, we were visiting Rome and Paris together for the first time. Then in 2019, last summer, she phoned me with the news.

Through tears, she said, “It’s back.”

The words my brain managed to pick up were stage IV, metastasized, the bones. She would have called sooner, she explained, but she didn’t want to interrupt my work. I was at an arts residency in New Hampshire for the month, finishing my manuscript. So, under sudden pressure and running out of time, I completed the first draft of my book the next day, unsure how to celebrate, unsure if I should.

The rest of my time at the residency, I wore Thé Vert. I wore it when I went to Manila to see my mother that fall—and again over the winter holidays, when it still felt safe to fly overseas. This year, I wore it at my pre-launch book party, when we could still gather in large groups. I wore it on a big date, when it still felt safe to date—to hug hello, to sip each other’s cocktails, to kiss.

I wore Thé Vert when I woke up terrified. Have worn it throughout the pandemic thus far. Even now, as I write this essay, I wear my mother’s perfume.

I’m not sure when I’ll get to see her again. She’s doing fine, all things considered. Regarding her cancer, I can say that there’s no ticking clock—not for now at least. But there’s also no assured end to the coronavirus crisis. According to experts, it could take anywhere from two months to a year and a half before we can reclaim even a few routines of the pre-COVID-19 world.

At the rate I’m going, I’ll run out of Thé Vert by then. I’ve been putting it on every morning in self-isolation. It keeps me calm, for the most part—as have the facts that I live alone; that I can do my job online; that I take a soapy shower after every trip to the grocery and liquor store; that I have books and video games and group chats to keep me entertained.

But that miasma, it lingers. Thé Vert cuts through it on most days, but when friends ask how I’m doing, I mention my ambient unease. My longing for a world we previously took for granted, a world to which we might never return. This fear, one I’ve felt since last summer, of looming death. The Harvard Business Review named my anxiety when it published an article about the coronavirus that said, right in the headline, “That discomfort you’re feeling is grief.”

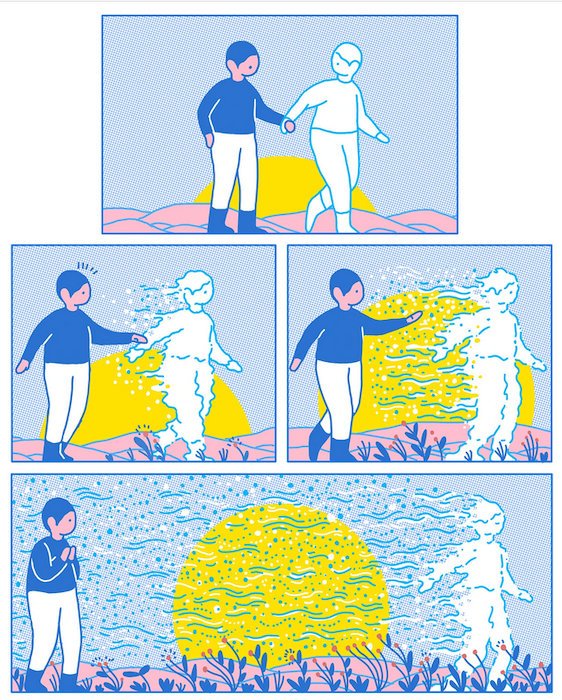

More specifically, anticipatory grief—the kind we experience when facing an unknowable future. In the case of the coronavirus, there’s an invisible enemy still mysterious to us, shattering our sense of readiness or safety. Everything is going to change, we think, but how? That’s exactly what I’ve been feeling since my mother said, “It’s back.” Her death is around the corner. We don’t know how long we have on this road, or when we’ll make that turn.

To grapple with anticipatory grief, the HBR article says, we must first acknowledge it—the terrifying days to come. Before making meaning out of loss, before mourning too fast, we must first manage the current grief with counteractive thinking. We must focus on the present. Like so: At this moment, I’m fine. I have food and a home, a job and a warm bed. I am not sick.

But my mother is sick. Already I feel the future pangs of loss; time-traveling micro doses of unbelievable hurt. We are already so far apart physically. Yet there will be a day, who knows how soon, when that gulf widens further, when she will no longer be just a 17-hour flight away. I will not be able to reach her by phone. My memories will fade and I will run out of Thé Vert—the ways I summon my mother.

I wore Thé Vert on a date so that this boy I liked could meet her, in a way. I wore it at my pre-launch book party in order to feel her presence too. I wore it in New Hampshire to celebrate with her a milestone in my writing career. All while we still can. These days, I’ve realized, I don’t wear the perfume to borrow her bravery, to emulate her. I wear it to feel her near me, to alleviate the present distance between us, the future loss I dread.

Like many others living in self-isolation, my mother and I find consolation in the little things: phone calls, video chats, the time we do have on earth. I’m getting antsy though. I told her I’ve been looking at tickets to Manila for my birthday in September, to celebrate with her and my stepfather once the pandemic is over.

“One day at a time, anak,” my mother said. “Take care of yourself first. That’s how we’ll make it through.”

She’s right. Though time differences remain and continents still drift, at least the world keeps turning. If we play our cards right as individuals and as communities in this time of certain uncertainty, there’s a future to hope for, to work towards.

I look forward to the day when I see her again in the flesh, when we embrace and hold each other. She will get a whiff of Thé Vert, still sharp and insistent after all these years, and rest easy. She’ll know that, wherever I go—or, one day, she goes—I will carry her with me always, even long after our perfume has faded into the night.

But for now, I must relish the present. At this moment, she’s fine. She has food and a home, my stepfather and a warm bed. My mother is alive.

It’s like another spritz, another vivifying hit.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!