When animals lose a member of their species, they often show behaviors that look like human grief. Does this mean they are mourning the dead?

By Leslie Nemo

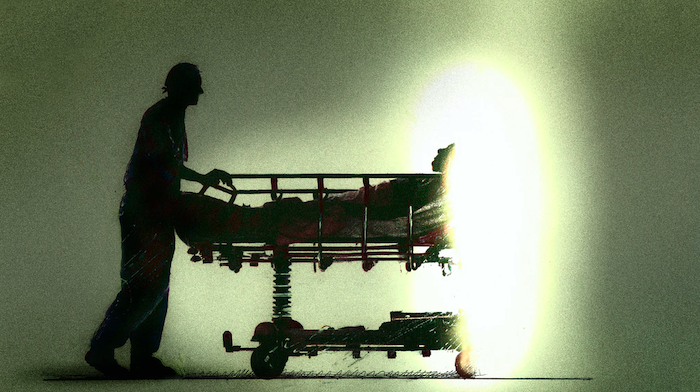

In August of 2018, millions of people watched a video of an Orca in the Pacific Northwest and felt their hearts break. The new mother named Tahlequah had lost her calf, but persisted in pushing the corpse around for 17 days. It was almost impossible not to feel, deep down, that the mom was grieving.

Scientists are tempted to draw those conclusions, too. But even if researchers feel that an animal’s behaviors mean it is mourning, that’s not how their job works. “We need documented evidence that this is indeed an analogue to grief,” says Elizabeth Lonsdorf, a primatologist at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, that proof is hard to get. “In terms of emotion, animal cognition is tricky,” she says. “It would be a lot nicer if you could ask them what they’re feeling.”

Since that option is off the table, scientists resort to observations, analysis and testing hypotheses to figure out why animals interact with their dead, and whether those interactions count as grief. And it’s going to take a lot more than just observations in the wild to get an answer. “The short answer is this is one of these great scientific problems that will take people working from all areas to sort out,” Lonsdorf says.

Rare Sightings

To begin with, it’s important to understand how rarely researchers see animals interact with the dead. Even if observations make headlines, those are single incidents. Scientists need a large dataset of interactions to reach any conclusions about why animals do what they do.

For many animals with documented behaviors toward deceased individuals, the field notebooks don’t have many entries. When Lonsdorf and her colleagues analyzed incidents of chimpanzee mothers carrying infant corpses for a study published in July, there were 33 total cases to work with — and that was after 60 years of research in the same chimp communities in Tanzania. Data is scarce for cetaceans, too. Between 1970 and 2016, there were only 78 recorded incidents of different dolphins and whales showing interest in a dead individual.

Observing these interactions in the wild is somewhat serendipitous. Unlike other animal behaviors, it’s not possible for researchers to head out into the field intent on observing interactions with the dead. “You can’t go out and wait for animals to die,” Lonsdorf says.

There’s also a chance that the incidents that do end up in studies are only the ones that intrigue us humans the most. As behavioral ecologist Shifra Goldenberg and her colleagues point out in their 2019 analysis of elephant behaviors, “There is probably a bias within this body of anecdotes that favors the recording of interesting or more obvious behaviors.” Even when compiling all recorded instances, finding a pattern of behavior can be hard if not all research groups know or document the exact same details every time. These details might include how long the interactions were, who showed up, or the exact nature of the relationships between the living and deceased.

Using Context Clues

Researchers can still take a close look at the ways in which different animals interact with the dead to try and suss out their motivations. For example, some scientists have proposed that maybe a given species nudges, touches or carries a corpse because they don’t yet know their child or friend is, well, dead. When it comes to cetaceans, like dolphins and whales, many biologists think that within a few days of interaction, the living individual would have figured it out. After all, their motionless companion starts to reek of decay. But there’s still no concrete evidence that the aquatic mammals are aware that the individual won’t be revived. “Though research into this realm started over fifty years ago,” wrote zoologist Giovanni Bearzi and his colleagues in their 2018 analysis of these cases, “there has been little direct research on this topic and the matter is still open to investigation and debate.”

With chimpanzees, it’s a different story. In their study, Lonsdorf and her team analyzed the same possibility — that mothers didn’t realize their child had died — but found evidence to suggest otherwise. The moms sometimes dragged the infants, something they’d never do while their child was alive. In some cases, they cannibalized their young, a pretty clear indicator that they knew something had changed. Other theories about why these mothers interacted with their deceased kids didn’t fit the evidence, either. One idea was that mothers are so overwhelmed with the postpartum hormones influencing their maternal instincts that they can’t bring themselves to let go of their child. If that was the case, then the research team would have seen mothers who lost older kids let go faster, as they’d be well past the wave of hormonal attachment. But there wasn’t any relationship between infant age and how long the mother carried the body around.

When their analysis was done, Lonsdorf and her colleagues were left with the impression that chimp mothers know their child has died, but still can’t let go — even grooming their baby as if it were still alive. But that doesn’t mean the team concluded that these primates were feeling grief. “Our conclusion was, ‘Okay, at least for chimps, the simple solutions don’t work.’ We need to think more creatively.”

Understanding Grief

To better understand why chimps — or elephants or cetaceans or any number of animals — interact with their dead, more nuanced research needs to happen. When it comes to chimpanzees, maybe experiments with captive individuals could show how they react to, say, photos of deceased friends. After a death, primatologists could look for changes that mirror some common human grief behaviors, like withdrawing from others or losing interest in food, Lonsdorf says. For cetaceans, Bearzi and his colleagues think that it might be worth trying to record the sounds the marine mammals make after a death, as many species are famous for intricate echolocations.

A better understanding of animal behavior could use some introspection, too. Grief is a vague, variant concept and process for humans, and even death itself comes with a learning curve. Lonsdorf, for example, remembers watching Star Wars as a kid and believing the actor who played Obi-Wan Kenobi actually died on screen. “I was shocked when he showed up in another movie,” she says. Death and grief can still seem strange and unfamiliar to us. Naturally, a more nuanced understanding of those concepts in people might help us recognize them in other creatures, too.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!