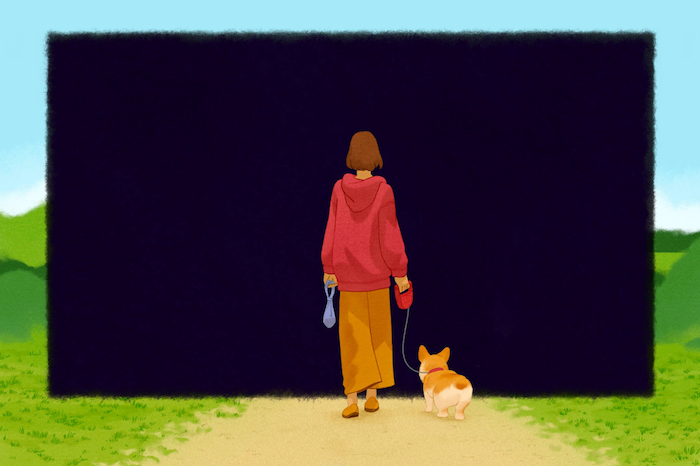

Sarah Weaver has combined tragedy and comedy in her webcomics as a way to cope with the death of her older sister

By Ashley Nerbovig

Monotony was kindling for Sarah Weaver’s burning grief.

After the June 2010 death of her older sister, Melissa Weaver, in a plane crash in Northwest Montana, Sarah would fumble over familiar questions such as, “How many siblings do you have?”

The tragedy shook Sarah’s entire worldview. For years she plodded along. She moved to Washington D.C. and took a job creating retirement policy at the U.S. Department of Treasury. Her boss would tell her the work she did made a meaningful difference. But Sarah didn’t see it. In 2016, she wondered whether she’d chosen where she was, or if she’d just ended up there.

In two years, Sarah traveled to 45 countries on six continents. When her travels ended, she returned to Polson, settling near where Melissa lived before she died. And now, 10 years after the plane crash, Sarah is using her webcomic, “Adventures with Vrah” to write about death, depression and diarrhea.

The combination of tragedy and comedy was appealing.

“It’s what has helped me cope and move through my own grief,” Sarah, 32, said. “I think it might help other people, or hope that it will help other people.”

Sarah was living in London at the time and staying with her aunt and uncle. She was about a week into an internship when she opened a Facebook message that read “Sarah, I’m so sorry to hear about your sister. Let me know if I can do anything.”

The cryptic message left her scared and confused. The surreal feeling stayed with her as she got ahold of her parents. They were already in Polson with Sarah’s other two siblings, Emily and Joe, trying to get more information about the whereabouts of Melissa’s plane.

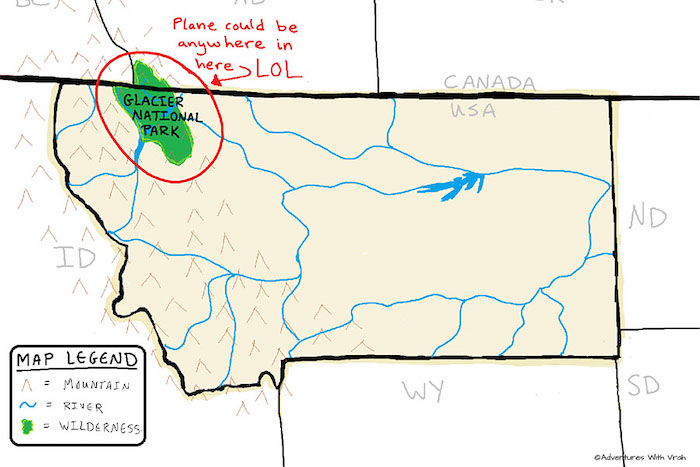

On June 27, 2010, Brian Williams and newly licensed pilot, Sonny Kless, picked up Melissa and her friend Erika Hoefer for a sightseeing trip over Glacier National Park. A woman reported seeing the plane, but no one reported seeing it crash. Officials believe the plane lost lift over a box canyon near the National Bison Range, roughly 100 miles south of the West Glacier entrance to the park, and dropped out of the sky.

A flight plan wasn’t filed before the four left, which made it difficult for rescue teams to know where to look. Sarah remembers hoping Melissa would be found alive. But their mother, Kathy Weaver, said she knew the moment she heard the plane went missing that Melissa was dead, even if a very small part of her thought that if Melissa did survive the crash, she would do anything to come home. She’d walk on two broken legs, Kathy said.

After three days of searching, the crash site was found. The plane had caught fire. Melissa, Hoefer, Williams and Kless all died in the crash.

“For years I’d hope that they were wrong,” Sarah said. “I’d think, ‘Everything was burned, so how do they even know it was the right plane?’”

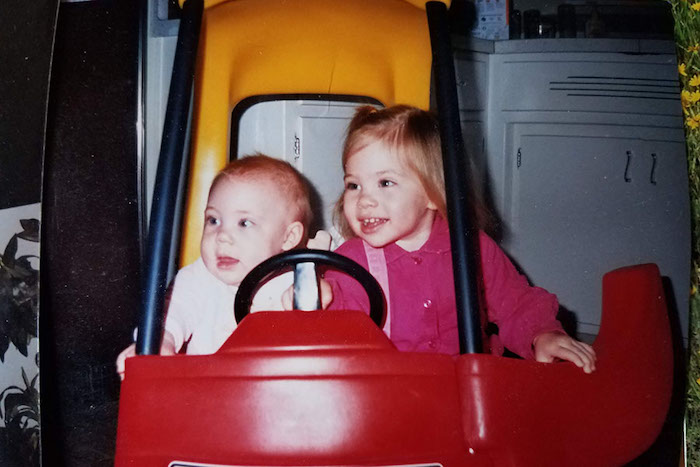

Melissa, who was the oldest of the four Weaver siblings, was 23 when she died. Sarah, 21 at the time and 18 months younger than Melissa, was thrust unprepared into the oldest sibling leadership role. Emily Weaver, who was 19, had finished her first year of college. Joe, 17, was still in high school and living in Billings with their parents, Kathy and Dan Weaver.

For Sarah, a large part of working through the Melissa’s death was scribbling down her thoughts and doodling. It started as a way to keep memories of Melissa fresh, a way to help her siblings remember Melissa, who was four years older than Emily and six years older than Joe. Sarah wasn’t an artist. She’d studied finance at UM. But, after she showed one of the comics she’d made to a friend, he encouraged her to share it online. She launched her comic site in 2016, and since then her style has continued to evolve. One of the inspirations for her series was Allie Brosh, the creator of “Hyperbole and Half” and a fellow University of Montana graduate.

Years before Melissa died, Sarah watched a movie about a wife who called her husband’s cellphone and listened to his voicemail while crying in bed. It was one of the saddest things she’d ever seen, she said.

“So when Melissa died, I remember thinking back to that scene and being like, ‘I’m in the sad movie,’” Sarah said.

Sarah would still call Melissa and send her Facebook messages until one day when she called, a man answered. Melissa’s cellphone number had been reassigned to a stranger. It was devastating, but Sarah didn’t want to stop calling her sister, so she kept calling Jeff. She pretended they were lifelong friends. Jeff usually hung up on her.

One day, she got a text from Jeff’s son, telling her she was freaking out his dad and to please stop calling. She did, but she still hopes that Jeff will realize one day why she called so often and they’ll become friends. She never explained why she had “his” number. She never told him about Melissa. The comic she made about the experience with Jeff is one of her family’s favorites.

“It was just easier to play a character, a game — it was too sad,” Sarah said. “What if he did care why I was calling him?”

As Sarah’s perspective on Melissa’s death evolved, so did the webcomic. It stopped being about who Sarah was without Melissa and became about Sarah.

After spending two years abroad, Sarah returned to live in Polson. She set up a Patreon for her webcomic and thinks about turning it into a book one day. In moments of uncertainty, she wonders if it’s wrong to link her career path to her sister’s death, but ultimately she hopes her art could help people.

Emily understands Sarah’s doubts but believes in her mission.

“The fact of the matter is, it happened, and we have to make as much good of it as we can,” Emily said.

Melissa’s death set off a chain of events, including unexpectedly positive developments. For one, Emily transferred from Carroll College to the University of Montana to live with Sarah after Melissa’s death and met her husband there. But the family members were isolated from one another in their grief, Emily said, and it took awhile for them to repair themselves. Every year that passes, it gets better.

The family got together this year on the 10th anniversary of the plane crash. For the first time, it felt like it wasn’t just about being sad about Melissa’s death, Emily said.

“It feels like everyone’s gotten through some of their grief,” Emily said, “and that let us come back together as a family.”

The siblings’ father, Dan, said his grief over Melissa’s death is like a heavy coat he has to wear year round. It unnerved him at first that Sarah was going to write about it. Over time, though, he’s gotten more enjoyment from Sarah’s comic. He learns things about the kids that he’d never known.

The public nature of the comic has been beneficial to Sarah. Beyond people writing to say how her comic helped them, having it as her full-time job forces her to be frank with people about her life. The process of writing and explaining it to people, sometimes in different languages, made it easier to answer the questions that stumped her after Melissa died.

Before she and her husband took their two-year trip all over the globe, they’d gone on a shorter trip to Indonesia. There, a woman asked Sarah what she did for work. When Sarah showed the woman a translation of her comic’s themes, the woman pointed to the word “depression” and said, “Yes, I know this.”

“It helps me,” Sarah said. “It’s powerful when someone can say, ‘I know, maybe, a piece of your pain.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!