By James Michael Dorsey

Not all cultures believe in burying the dead in the ground. Here are 10 unique ceremonies from around the world.

THE MODERN DICTIONARY defines the word ‘burial’ as placing a body in the ground.

But burying the deceased was not always the case.

Just as primitive man has long worshiped the four elements of Earth, Sky, Water, and Fire, so too have these elements taken their place in burial practices as diverse as the different tribes of the earth.

The way mankind deals with its dead says a great deal about those left to carry on. Burial practices are windows to a culture that speak volumes about how it lives.

As we are told in Genesis, man comes from dust, and returns to it. We have found many different ways to return. Here are 10 that I found particularly fascinating:

Air Sacrifice – Mongolia

Lamas direct the entire ceremony, with their number determined by the social standing of the deceased. They decide the direction the entourage will travel with the body, to the specific day and time the ceremony can happen.

Mongolians believe in the return of the soul. Therefore the lamas pray and offer food to keep evil spirits away and to protect the remaining family. They also place blue stones in the dead persons bed to prevent evil spirits from entering it.

No one but a lama is allowed to touch the corpse, and a white silk veil is placed over the face. The naked body is flanked by men on the right side of the yurt while women are placed on the left. Both have their respective right or left hand placed under their heads, and are situated in the fetal position.

The family burns incense and leaves food out to feed all visiting spirits. When time comes to remove the body, it must be passed through a window or a hole cut in the wall to prevent evil from slipping in while the door is open.

The body is taken away from the village and laid on the open ground. A stone outline is placed around it, and then the village dogs that have been penned up and not fed for days are released to consume the remains. What is left goes to the local predators.

The stone outline remains as a reminder of the person. If any step of the ceremony is left out, no matter how trivial, bad karma is believed to ensue.

Sky Burial – Tibet

This is similar to the Mongolian ceremony. The deceased is dismembered by a rogyapa, or body breaker, and left outside away from any occupied dwellings to be consumed by nature.

To the western mind, this may seem barbaric, as it did to the Chinese who outlawed the practice after taking control of the country in the 1950s. But in Buddhist Tibet, it makes perfect sense. The ceremony represents the perfect Buddhist act, known as Jhator. The worthless body provides sustenance to the birds of prey that are the primary consumers of its flesh.

To a Buddhist, the body is but an empty shell, worthless after the spirit has departed. Most of the country is surrounded by snowy peaks, and the ground is too solid for traditional earth internment. Likewise, being mostly above the tree line, there is not enough fuel for cremation.

Pit Burial – Pacific Northwest Haida

Before white contact, the indigenous people of the American northwest coast, particularly the Haida, simply cast their dead into a large open pit behind the village.

Their flesh was left to the animals. But if one was a chief, shaman, or warrior, things were quite different.

The body was crushed with clubs until it fit into a small wooden box about the size of a piece of modern luggage. It was then fitted atop a totem pole in front of the longhouse of the man’s tribe where the various icons of the totem acted as guardians for the spirits’ journey to the next world.

Written history left to us by the first missionaries to the area all speak of an unbelievable stench at most of these villages. Today, this practice is outlawed.

Viking Burial – Scandinavia

We have all seen images of a Viking funeral with the body laid out on the deck of a dragon ship, floating into the sunset while warriors fire flaming arrows to ignite the pyre.

While very dramatic, burning a ship is quite expensive, and not very practical.

What we do know is most Vikings, being a sea faring people, were interred in large graves dug in the shape of a ship and lined with rocks. The person’s belongings and food were placed beside them. Men took their weapons to the next world, while women were laid to rest wearing their finest jewelry and accessories.

If the deceased was a nobleman or great warrior, his woman was passed from man to man in his tribe, who all made love to her (some would say raped) before strangling her, and placing her next to the body of her man. Thankfully this practice is now, for the most part, extinct.

Fire Burial – Bali

On the mostly Hindu Isle of Bali, fire is the vehicle to the next life. The body or Mayat is bathed and laid out on a table where food offerings are laid beside it for the journey.

Lanterns line the path to the persons hut to let people know he or she has passed, and act as a reminder of their life so they are not forgotten.

It is then interred in a mass grave with others from the same village who have passed on until it is deemed there are a sufficient number of bodies to hold a cremation.

The bodies are unearthed, cleaned, and stacked on an elaborate float, gloriously decorated by the entire village and adorned with flowers. The float is paraded through the village to the central square where it is consumed by flames, and marks the beginning of a massive feast to honor and remember the dead.

Spirit Offerings – Southeast Asia

Throughout most of Southeast Asia, people have been buried in the fields where they lived and worked. It is common to see large stone monuments in the middle of a pasture of cows or water buffalo.

The Vietnamese leave thick wads of counterfeit money under rocks on these monuments so the deceased can buy whatever they need on their way to the next life

In Cambodia and Thailand, wooden “spirit houses” sit in front of almost every hut from the poorest to the most elaborate estate. These are places where food and drink are left periodically for the souls of departed relatives to refuel when necessary. The offerings of both countries also ask the spirits of the relatives to watch over the lands and the families left behind.

Predator Burial – Maasai Tribe

The Maasai of East Africa are hereditary nomads who believe in a deity known as Enkai, but this is not a single being or entity.

It is a term that encompasses the earth, sky, and all that dwells below. It is a difficult concept for western minds that are more used to traditional religious beliefs than those of so-called primitive cultures.

Actual burial is reserved for chiefs as a sign of respect, while the common people are simply left outdoors for predators to dispose of, since Maasai believe dead bodies are harmful to the earth. To them when you are dead, you are simply gone. There is no after life.

Skull Burial – Kiribati

On the tiny island of Kiribati the deceased is laid out in their house for no less than three days and as long as twelve, depending on their status in the community. Friends and relatives make a pudding from the root of a local plant as an offering.

Several months after internment the body is exhumed and the skull removed, oiled, polished, and offered tobacco and food. After the remainder of the body is re-interred, traditional islanders keep the skull on a shelf in their home and believe the native god Nakaa welcomes the dead person’s spirit in the northern end of the islands.

Cave Burial – Hawaii

In the Hawaiian Islands, a traditional burial takes place in a cave where the body is bent into a fetal position with hands and feet tied to keep it that way, then covered with a tapa cloth made from the bark of a mulberry bush.

Sometimes the internal organs are removed and the cavity filled with salt to preserve it. The bones are considered sacred and believed to have diving power.

Many caves in Hawaii still contain these skeletons, particularly along the coast of Maui.

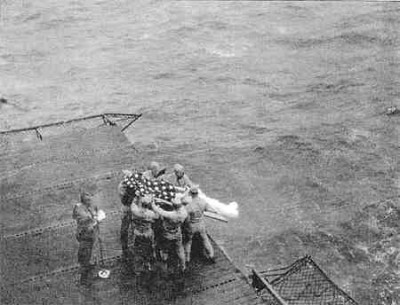

Ocean Burial

The open sea

Since most of our planet is covered with water, burial at sea has long been the accepted norm for mariners the world over.

By international law, the captain of any ship, regardless of size or nationality has the authority to conduct an official burial service at sea.

The traditional burial shroud is a burlap bag, being cheap and plentiful, and long in use to carry cargo. The deceased is sewn inside and is weighted with rocks or other heavy debris to keep it from floating.

If available, the flag of their nation covers the bag while a service is conducted on deck. The body is then slid from under the flag, and deposited in Davy Jones locker.

In olden days, the British navy mandated that the final stitch in the bag had to go through the deceased person’s lip, just to make sure they really were dead. (If they were still alive, having a needle passed through their skin would revive them).

It is quite possible that sea burial has been the main form of burial across the earth since before recorded history.

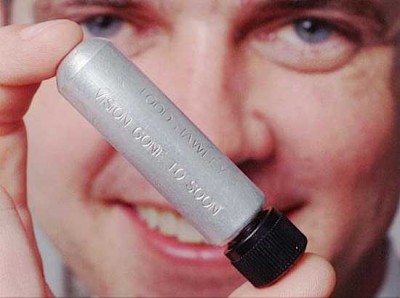

The Final Frontier

Today, if one has enough money, you can be launched into space aboard a private commercial satellite and a capsule containing your ashes will be in permanent orbit around the earth.

Perhaps this is the ultimate burial ceremony, or maybe the beginning of a whole new era in which man continues to find new and innovative ways to invoke spirits and provide a safe passage to whatever awaits us at the end of this life.

Any other death ceremonies you’ve encountered? Share your thoughts in the comments!

Complete Article HERE!