It would be foolish to think that we can control when our time is up. But neither should we face that moment unprepared. Not only for our sake, but for the people we leave behind.

By Vivien Shiao

[T]HE only certainty in life is death. But this is not something we like to think about – not when we are at our prime, our careers powering ahead, and the future bright. In fact, as you flip through the papers, about to tuck into a nice brunch with loved ones, you may even question why we want to mention it at all, potentially casting a pall on a perfectly good weekend. The reality is, there are just as many ways to die as there are ways to live. It can come like a thief in the night, sudden and without warning. For others, death comes as an impending train – relentless and closing in. Or sometimes, long after the body and mind have withered, death still does not come. As the ultimate human experience we all cannot run away from, it matters how we approach death. How we live the rest of our days depends on it.

What a good death means

A good death is hard to define. In many instances, the process of dying is described as a battle to be won, a fight between life and death. Rage, rage against the dying of the light, wrote poet Dylan Thomas.

But doctors intimate with death tell The Business Times that this struggle to extend life without thought to its quality is not necessarily what people want.

Dr Ng Wai Chong, chief of clinical affairs, Tsao Foundation, is a physician who is well acquainted with death. To him, a good death is the ultimate challenge. “It is one with a good mind, one that is peaceful, one that has closure. All the big questions in life have been answered… To prepare for a good death, you need to live a life that is responsible and with a clear conscience.”

Those who are prepared are typically contented, accepting and also grateful, says Dr Ng. For Dr Neo Han Yee, a palliative care consultant at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, a good death means a life of little regret or guilt, and being at peace knowing that loved ones will be taken care of. “It is difficult to achieve zero suffering, but on a spiritual aspect, these people feel that their lives have been worthwhile and they are ready to move on.”

A good death also has a social dimension, he explains: People with the “foresight” to invest their time and effort in relationships, in turn, receive support in their last days from family and loved ones. They are the ones with the wisdom to prepare early and help family members cope with their impending passing, he says.

Planning for the end

A good death doesn’t come by accident. It takes planning and preparation in many aspects – financial, legal, psychological, social, medical, and even spiritual – to make it happen. This is not just to ease one’s passage, but also to ease the burden on loved ones.

If the end-of-life process is a long drawn out one, the stakes are even higher. For example, if you become mentally incapacitated due to your illness and your children have no idea what your last wishes are, they could end up spending tens of thousands trying to treat you, in the hopes of extending life.

Not only could this increase your distress in your last days (though with no ill intention), the lack of clarity is likely to result in conflict among family members, and financial issues. Such a scenario may seem like the stuff of TV dramas, but it is a lot more common than you think, according to experts that BT spoke to. So, rather than wait for a crisis to strike, it may be prudent to plan ahead when things are hunky dory and you still have sound presence of mind. This could prevent unnecessary expenditure, heartache and headache for others further down the road.

Alfred Chia, CEO of financial advisory firm SingCapital, says that procrastination is one of the biggest mistakes that people tend to make regarding their finances. He is also the co-author of Last Wishes: Financial Planning, Will Planning and Funeral Planning in Singapore. “Planning for death should not be viewed as taboo or negative. In fact, it is a celebration of our life in this world,” Mr Chia says. He advises people to plan for retirement early to avoid “huge financial stress” later. Work out the amount needed each month for the ideal lifestyle post-retirement and the number of years you expect to provide for, he says. The right insurance policy can also help achieve your goals in a more cost-effective way, he adds.

Other mistakes he has observed others make is to fall prey to financial scams, and to invest in instruments that don’t suit their risk profile. He says: “There is a saying that when I pass on, I have not spent all my money. While that is a regret, it will be even more regretful if I have spent all my money, and yet am still alive with no capacity to earn an income.”

On the flipside of the coin, those who are extremely wealthy have even more compelling reasons to plan. To manage their wealth, they often turn to family offices – private wealth management advisory firms.

Mr Chia says that planning ahead for the wealthy can help keep family unity and prevent squabbles over inheritance. Family offices can also spread the distribution of wealth over an extended period so that the children won’t be “spoilt” with the sudden wealth, he adds.

Working with the law

When life ends, a host of issues crop up for loved ones, that can only be properly resolved within the confines of the law.

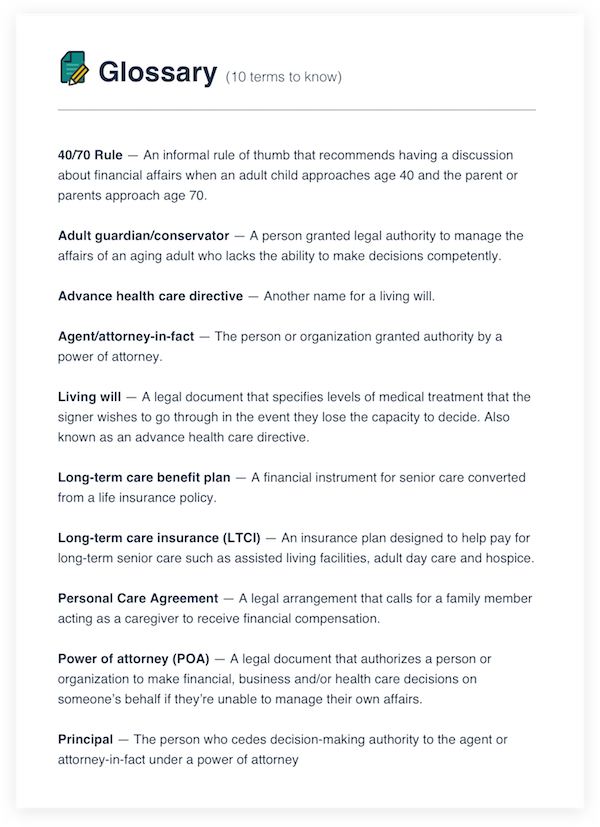

Most people know the significance of wills, but there are other considerations such as trusts and Lasting Power of Attorney, or the LPA.

A will is for the distribution of assets after one’s death, while an LPA is for the appointment of a person or persons (known as the donee) to make decisions for you on “health and wealth” before your death.

Doris Chia, litigation partner of David Lim & Partners, saysthat most people with elderly parents would want to do an LPA, so that they are able to access their parents’ bank accounts or assets to pay for their parents’ medical bills when their parents are unable to do so.

One thing to bear in mind is that the LPA only kicks in in the event of loss of mental capacity. So although you may do an LPA now, it may only be valid decades later, says Ms Chia. Or, it may never come into effect at all if the person who appointed the LPA remains mentally healthy.

Ms Chia also warns that the LPA comes under the Mental Capacity Act, which means it can only be made by a person of sound mind. Once there is an onset of a mental issue such as Alzheimer’s or senile dementia, it will be too late to make one.

The consequences can be serious. She cites an example where the mother of one client became mentally incapacitated and then fell ill, and the client was unable to sell a private property that she owned jointly with her mother.

Without an LPA, she had to apply to the court for deputyship to sell the property, to fund her mother’s medical needs. This process cost “tens of thousands of dollars”, according to Ms Chia.

“A person applying to be a deputy has to file several affidavits in court. This also costs money. You can save all this heartache now by doing an LPA. What’s the harm?”

According to the Office of the Public Guardian, the fee for LPA certificate issuers ranges from S$25 for a general practitioner to S$500 for a psychiatrist – still much more affordable than applying for deputyship.

Another group of people that Ms Chia urged to apply for LPAs are singles, and people who identify as LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender).

“For LGBT people, it is essential to do an LPA as it allows the partner – and not family members, if that is your choice – to make decisions on your personal welfare and property and affairs. Otherwise, legally, your partner has no say over such matters in such circumstances.”

Where there’s a will

Aside from the LPA, the will is another matter to be considered seriously. For non-Muslims who die without making a will, distribution of assets will be according to the Intestate Succession Act. For example, the surviving spouse will get 50 per cent of assets, with the rest divided among their children. For singles, the assets will go to their living parents. Otherwise, it will go to their siblings.

Muslims follow the Muslim intestacy law, the faraid. Only one-third of their assets can be willed away, with the rest distributed according to the faraid.

For those who don’t want to follow the standard distribution rules, making a will is vital. Some people, Ms Chia has observed, don’t trust their spouses too much and prefer to give everything to their children.

The existence of a will gives much quicker access to assets. For people who die with a will in place, a Grant of Probate allows the process to move much faster compared to the Letter of Administration for those who die without a will, says Ms Chia.

Even so, the existence of a will is no guarantee that it will be carried out. It may be hidden, or lost, or challenged. It’s important that the executors of the will – those who will administer and distribute your estate upon death – know where the will is, together with proper instructions on bank accounts, assets and insurance policies.

Details make all the difference. “I always say to my clients, do a will that can last many years,” says Ms Chia. “Don’t say Property A goes to one son, and Property B goes to another son. If you sell Property B and you forget to amend your will, one son will end up with nothing.”

Instead, she recommends that the executor be instructed to sell all assets and for the proceeds to be distributed according to percentages.

State of mind and health also matter. It’s better to make a will when you are healthy and of sound mind so that there will be no dispute later, Ms Chia advises. She observes that most people do not think about end-of-life decisions until they are forced upon them. But wills are sometimes contested if the person had made it when they were very old or very sick.

Giving the assets in a trust, as opposed to in a will, prevents challenges by family members, says Ms Chia. Often used for succession planning, a trust protects family assets for the good of beneficiaries who are either too young, financially immature or vulnerable until they either come of age or reach a certain maturity.

The assets put into a trust are a gift made in a person’s lifetime, and not upon his death. Once the assets vest in the trust, they no longer belong to him. The assets will not form part of his assets at the point of his death and hence, a trust cannot be contested, explains Ms Chia.

Having a trust could also mitigate the heavy taxes applicable to estate duty in certain overseas jurisdictions, or safeguard assets from the possibility of lawsuits by creditors.

One particular group that can benefit are family members with special needs, she adds. Setting up a trust with that particular person as the beneficiary is a way to plan for a day when one can no longer care for him or her in person, says Ms Chia.

A conversation about care

Perhaps, due to cultural mores, or perhaps the need to “protect” their parents, some children refuse to even talk about death with their elderly parents, even as it is looming.

Sometimes, the severity of their condition – or even the amount of time they have left – is deliberately kept from them by well-meaning family members, thinking that mentioning it will result in emotional instability.

TTSH’s Dr Neo observes: “Quite often, when a person is so sick, family members are pushed into a corner. They don’t know how to broach the topic.”

But doctors and healthcare professionals are actively trying to change this mindset with the introduction of the Advanced Care Plan (ACP). It is a voluntary discussion on future care preferences between an individual, his or her family and healthcare providers.

While not legally binding, it describes the type of care the person would prefer, if he or she is to become very sick and unable to make healthcare decisions in the future. Compared to the Advanced Medical Directive (AMD) which has a very narrow scope of criteria, the beauty of the ACP is in the conversation, says Dr Ng from the Tsao Foundation.

“The goal is to respect a person’s rights to self-determination. It encourages people to think about existential issues and helps the people conducting it to get into the value system of the person. Scenarios might change, but the general drift is there, so it will bring some clarity.”

Otherwise, caregivers who don’t know what patients want will end up going on the “path of least resistance”, which often means over-investigation of treatment, says Dr Ng.

An AMD allows you to register in advance your wishes not to have any extraordinary life-sustaining treatment to prolong life in the event that you become terminally ill and unconscious and where death is imminent. However, the definition of a “terminal illness” is extremely specific.

Among the wealthier and more educated patients or caregivers, Dr Ng has also observed a sub-group of people who approach medical conditions with a consumer attitude. Instead, he advocates having a doctor as a lohealth partner that you can trust, with a relationship built over a long time.

“I see people over-treat, over-investigate, but a primary care doctor is a better way of managing health. The person can help you clarify your purpose, your goals and the best strategy to proceed. Along the way, he can even do your ACP with you and be a facilitator when it comes to complex family dynamics.”

Beginning with the end

It is not just the medical aspect of health that people should take into account in their last days. There’s also the need to think about the social, emotional and psychological state of the person.

TTSH’s Dr Neo explains that the intensity of pain is often heavily coloured by one’s emotions. To cope with the end of life, people must build up psychological preparedness and fortitude, he says.

To him, thinking about death is constructive for thinking of life.

He observes: “Life is impermanent. You treasure people around you a lot more, you don’t waste time on things not worth it. You invest your time and effort in things worthwhile. You know how to value relationships much more, so when the time comes, you will be wiser as you have thought about it for a longer period of time.”

To build psychological maturity, he advises people to find a higher meaning in life, or a certain “calling”. Singaporeans tend to forget this, he notes, as we trudge along in our work and family life. Happiness is always projected in the future, instead of finding meaning in one’s current existence.

At the crux of it, people are too busy trying to beat each other or accrue financial gain to think about their own vulnerability, says Dr Neo.

“We live in a very illusory world. Only when a crisis hits then will the person be shaken and realise that life is fragile. If we don’t make mental, emotional and financial preparations before, you will find it hard to cope with the situation. We often underestimate how much we can prepare for death.”

No one can predict how much time we have left on this Earth. But if we put in as much thought about how we want to die as much as we think about how we want to live, surely our days here – limited though they may be – will be all the more precious and meaningful.

What you need to know

Will

- Make sure your executors can find it. Ms Chia from David Lim & Partners cites an incident when a client made a will and was so secretive about it that his family couldn’t find it after his death. Be aware also that:

- The will is sometimes contested if it was made at a time when the person was very old or ill.

- CPF nominations and insurance policies with a named beneficiary are not part of the will.

- Property – private or HDB – held in joint tenancy will automatically go to the survivor and hence cannot be part of the will for distribution.

Lasting Power of Attorney

- Can only be used when the person who makes it (the donor) loses mental capacity and is only valid when the donor signs it when he is of sound mind.

- One fear that people have about LPAs is that their children or donees can “help themselves” to the donor’s money when he or she is mentally incapacitated. Ms Chia debunks this: The money can only be used for the person’s welfare and medical expenses, and they will need to submit accounts to the Office of the Public Guardian, which serves to safeguard the interests of individuals who lack mental capacity and are vulnerable. In addition, more than one donee can be appointed to guard against dishonesty.

Trust

- Anyone can set up a trust, says Ms Chia, but the costs are higher compared to arranging a will, or even setting up a private interest foundation, an entity which has the characteristics of both a company and a trust. “If the trust requires professional trust managers to make investment decisions or payments over several generations, this will cost money to administer. One needs to weigh the asset value against the cost of administering the trust,” she says.

Advance Medical Directive

- Legally binding, but very narrow definition of “terminal illness”.

- The AMD registry is only accessible during office hours. A doctor facing an emergency situation in the night will be unable to retrieve and verify an AMD. In fact, the AMD Act Section 15 has also been frequently interpreted as an offence for a doctor to query his patient about his AMD, according to Dr Neo of TTSH.

Advance Care Plan

- Puts everyone on the same page, as it describes the type of care you would prefer, if you become unable to make healthcare decisions in the future. U For people with an ACP, the palliative care is much smoother for everyone involved as they don’t feel burdened with tough decisions, says Dr Ng of Tsao Foundation.

- Not legally binding, and can be changed and reviewed, preferably with your primary care doctor or the main doctor tending to your advanced illness.

Complete Article HERE!