Jennie Dear has an evocative piece for us examining the scant evidence that scientists have so far about the mysterious threshold between life and death—what the body goes through and how a person subjectively feels it, both in terms of pain and hallucinations:

“A lot of cardiac-arrest survivors describe that during their unconscious period, they have this amazing experience in their brain,” [neuroscientist Jimo Borjigin] says. “They see lights and then they describe the experience as ‘realer than real.’” She realized the sudden release of neurochemicals might help to explain this feeling. … Most of the patients interviewed [for a study at a hospice center], 88 percent, had at least one dream or vision.

One reader says of Dear’s ostensibly morbid piece (“What It Feels Like to Die”): “The article is comforting in a way I did not anticipate.” Another reader agrees:

I kissed my dad goodbye on the forehead right before he died. He smiled briefly. So, this article was some comfort in maybe explaining that smile of his.

This next reader also lost her father:

I remember when my dad was dying, and my mom forbade any of us from telling him that he was dying. I thought that that was terribly selfish on her part, and I told my husband that if I were dying I would want to know.

When my mom passed away, she was “treated” to the experience of my sisters bitterly arguing as to who was the favorite. (I knew I wasn’t and just held her hand.) My husband got my sisters to stop. Finally, the doctors came in and actually said she had permission to die … Mom was like that; you had to have permission in her mind for everything.

My dear husband is gone now, and I just hope that when I go, I’ll be thinking of him.

That reader’s line—“if I were dying I would want to know”—prompted a question in my mind I’ve long answered in the affirmative: “Do you want to be awake for your death and know it’s coming?” The conventional wisdom says most people prefer to die in their sleep, but, as long as there’s no intense pain involved, sleeping seems like a disappointing way to experience one of the most profound parts of life—it’s ending. And whenever I think of that question, I’m reminded of these lyrics from Björk’s “Hyperballad”:

I imagine what my body would sound like

Slamming against those rocksAnd when it lands

Will my eyes be closed or open?

Would you rather be sleep or awake? How exactly would you prefer to die? What’s the ideal situation? Email hello@theatlantic.com if you’d like to share.

Back to a few more stories from readers regarding the death of a loved one. This memory is particularly poignant:

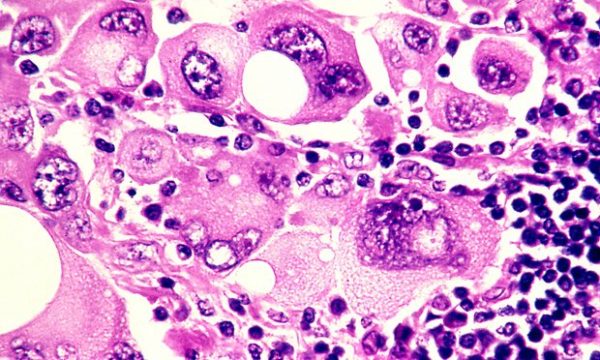

Twelve months ago, my 33-year-old daughter Phoebe began to die from metastatic melanoma. Over the next 10 weeks at a hospital in Melbourne, she went through each of the experiences outlined in Jennie Dear’s article. During this time, Phoebe asked her nurse how would she know when she was about to actually die. Donna told her that something would happen and she would know—both vague and oddly specific, but Phoebe was satisfied.

A week before her death, having gotten her pain under control, Phoebe was at home to say goodbye to her animals, clean out her cupboards, and give away her possessions. She was standing in the yard throwing a ball for the dog when she suddenly sat down, as I watched from the kitchen. I’m sure she realized as she collapsed to the bench that her time had come. I doubt that there could be a lonelier moment in a person’s life.

She didn’t speak again. Her hearing and hand gestures reduced over a few days to squeezing, then nothing but breathing quietly. Her brother-in-law, who was with her at the end, said she simply stopped breathing.

Each person’s death is different, so I found Dear’s article comforting in a way I did not anticipate.

One more reader for now:

My father was put into hospice, and all his meds were stopped. He “recovered” and lived another six months. After they “kicked him out” of hospice, he and I spent a lot of quality time together. When the end came, he was ready even though he could no longer speak. The hospice nurse came and looked at all the meds and found that while we still had the liquid morphine, we no longer had the Ativan, so we ordered a stat delivery from the pharmacist.

Giving morphine to a dying person can feel a lot like murder, and listening to the death rattle is more distressing than listening to a crying infant, but I think that the death experience is far worse for the person attending the death than for the one who is dying.

The Ativan was given to my father late in this process, but that was the drug which provided him with joy and relief. Shortly after he received the drug, I believe I witnessed him greeting his mother who had died 40 years ago.

My father then developed what is called a Cheyne-Stokes respiration; he would breath rapidly for a few minutes and then stop breathing. He resumed breathing like clockwork at 65 seconds from his previous breath. This lasted for hours. His last breath sounded much like a laugh, and I thought it was his way of saying good-bye.

I thought the event would be gruesome, but it was a special bonding experience which has helped me to reduce my fear of dying.

Complete Article HERE!