By Christine Colb

[E]vi Numen, 33, of Philadelphia, could be considered a little death-obsessed. She’s the curator and founder of Thanatography.com, a site that showcases the work of visual artists exploring the themes of death, grief, and loss. Previously, she worked at the Mütter Museum, known for its collection of medical oddities and pathological specimens, such as presidential tumours, murderers’ brains, and books bound in human flesh. She has also recently added a line to her résumé — she’s a “death doula” in training — one of the first in the United States.

Numen can be excused for being a little morbid. When she was 20, she survived a car accident that killed her partner on impact. Earlier that night, he had told her he was going to propose. While in the hospital recovering from her injuries and raw with grief, she kept asking if she could see his body in the morgue. “I needed to confront his death to truly believe it,” Numen says. “My doctors thought I couldn’t take the sight of him, dead and broken, but to this day I believe it would have helped. Seeing him in his coffin during the funeral a week later felt staged and artificial.”

Last April, when her late partner’s father was in rapid decline with cancer, Numen rushed to his side. “I held his hand, listened, and talked to him when he could, and also allowed his loved ones to take a break from the bedside. What I couldn’t do for my partner, I tried to do for his father.”

A large part of the assistance Numen provided was for his family. “I had to remind them it was okay to take care of their own needs. I couldn’t “fix” anything, but I could bring food so it was there when people needed it, or stay by the bedside and encourage family members to go for a brief walk to get some fresh air.”

Caregivers [of the dying] often need to be ‘given permission’ to care for themselves properly.

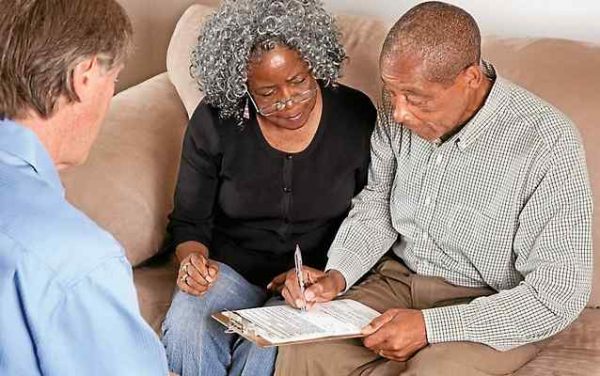

After her partner’s father died, Numen knew she had found her new calling. She did some research and found the International End of Life Doula Association (INELDA). “Immediately, I knew this was the right next step,” says Numen. Cofounded by former hospital social worker Henry Fersko-Weiss in February 2015, INELDA trains people to provide emotional support for the dying — and their family members. Ferko-Weiss was inspired by the concept of doulas who support a mother and her partner during pregnancy and childbirth. “I kept seeing people die in ways that I thought were unfortunate or even tragic. I was trying to figure out how to change that. To me, the principles and spirit and techniques of birth doulas could be interpreted and adapted for the end of life,” says Ferko-Weiss.

A certified death doula can help not only the dying person, but will assist their loved ones throughout the entire death process, from coming to terms with mortality weeks or even months before the death to remembering and memorialising their loved one after passing.

Numen took a 22-hour training with INELDA and has logged more than 20 hours of volunteer training at two different area hospices. She’s been coached to become familiar with the physical changes the body goes through directly preceding death — and in helping comfort and counsel the dying person and their family from the point of a terminal-illness diagnosis all the way through even a year after a death. “I think many of us have the tendency to be problem-solvers and try to offer solutions to someone who is hurting, but there is no solution to dying,” Numen says. “It is easy to develop the habit of offering platitudes to such a situation, such as, ‘This too shall pass.” But that’s not actually comforting to a grief-stricken person. I know this from my own experience. Instead, I serve as an active listener, letting the other person really talk about all their conflicting emotions.”

Numen says that one of the most fascinating parts of her training was learning how to recognise when the person is “actively dying.” “Most of us know what the birthing process is like — foetal development, labor, contractions, water breaking, and such are fairly common knowledge in the Western world. Yet very few of us know anything about what it looks like to die: Your appetite decreases, your skin changes colour, breathing sounds different. There is a huge discrepancy in how we view the two ends of human life. It is easy to see how such ignorance about death can lead to avoidance and fear.”

Numan had asked the nurses at a hospice where she was volunteering to call her if they needed someone to keep vigil for an imminently dying patient, especially if their family couldn’t be there. “My objective was to be with the person who needed me the most,” she says. She was called to the bedside of an elderly man in end-stage pulmonary disease. He had no family present and was unable to communicate. She was his sole companion in his final moments. She knew from her training that he only had a few hours of life remaining.

Over the course of seven hours, Numen played Clint Mansell, Erik Satie, Rachmaninoff, and Chopin on her iPad as she sat by the man’s bedside and watched him breathe. “His breath cycles grew further and further apart, but only by seconds, which to me felt like minutes as I found myself holding my breath with him,” says Numeb. “I knew he was very near. Within an hour, his breath got steady but oddly mechanical, more like a reflex than an action, and then the next inhale never came. I called the nurse and she confirmed the death. It was easier and more peaceful than I thought it would be, and yet it affected me more than I expected. I had, after all, trained for this, read about it, and kept vigil to other dying patients, but his passing was the first I had witnessed.”

Despite all her preparation, Numen was so deeply affected by the experience that she had to skip her next scheduled shift. “Being there for that man, when no one from his family was able to, affected me more than I thought it would,” she says. “I didn’t cry — I felt it wasn’t my place to, like I was just a stand-in for his family. There is a weird sense of intruding, especially when keeping vigil for complete strangers, that I have not been able to reconcile yet.” It also had a personal resonance for her. “Witnessing a death brought up the other losses in my life, and I had to honour these emotions before I could return to keeping vigil for someone else,” Numen explains.

Witnessing a death brought up the other losses in my life, and I had to honor these emotions before I could return to keeping vigil for someone else.

Despite her unanticipated reaction, she is even more committed to her calling of caring for the dying than she was before. “It wasn’t gross or scary, but it was certainly difficult. Every death will be different, and maybe it will get easier or less nerve-wracking, but it will not get any less worthwhile. Even if I never get to talk with the patients I attend to, knowing that I brought some small amount of comfort is enough.”

She’d also like to see more people become comfortable with ageing and the dying process. In a culture where ageism is rampant, Numen has found that learning about the end of life has actually made her less apprehensive of getting older — and the inevitable end. “Most of the patients I’ve seen close to death were peaceful and tranquil. They seemed comfortable and had this beautiful glow about them, this serenity that I didn’t expect to see. I’m still fearful of sudden death and the suffering of prolonged illness, but not of the dying itself.”

Numen also hopes that more family members will recognise that a death doula can be an option that can bring enormous comfort in someone’s final moments. “It’s about regaining control over an uncontrollable process,” she says.

Complete Article HERE!