As a culture, Americans—more often than not—have a tendency to avoid thinking and talking about death and dying. Yet pondering our mortality can have a profound impact on our lives.

Our health care system is set up with a single, default pathway for all medical care: aggressive, invasive treatment, no matter how old or how sick you are. For some people, this makes perfect sense and can save lives. For others, a different approach to care is required. But it starts with having a relationship with our own mortality and reflecting on what matters most in our own lives. I have seen far too many people suffer by receiving treatment that is not in line with their goals and values.

In our modern era of fast-paced life, constant digital connectedness, and a culture striving to be “doing” all the time, it’s easy to get caught up in things that don’t matter. If we can reflect on the bigger picture in life, the preciousness of each moment, we can more easily let go of things that aren’t important. I believe there are three key benefits to thinking about our mortality at least once a day:

1. You’ll be motivated to leave a legacy.

Ask yourself, what do you want to leave behind? The idea of legacy awareness is a way to connect with our own mortality as it relates to our work, loved ones, and creative endeavors. If we think about legacy as a means to transcend death, we may be more likely to invest in our health and personal development throughout life.

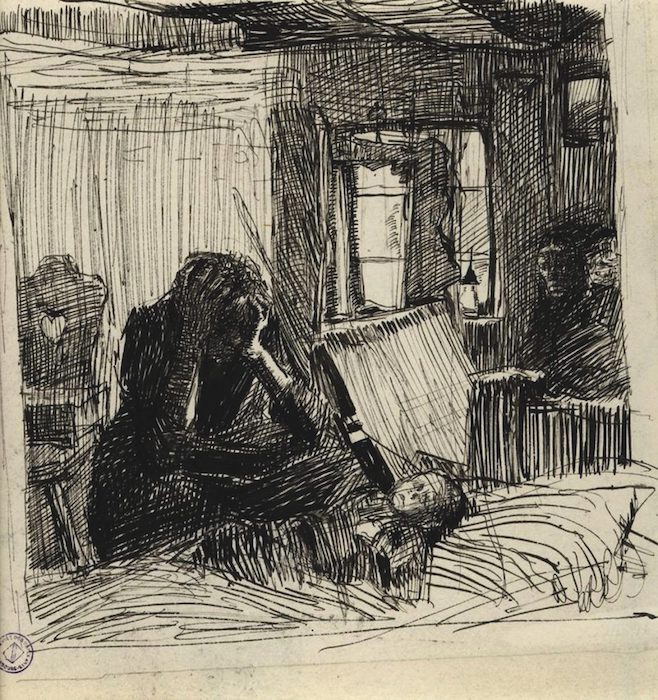

Artists, for example, live on long after they’re gone thanks to their creative legacy. That’s just one way of forming a legacy. Whether you are creating art, giving back to your community, raising a family, or making a positive impact on the lives of others, these are all powerful ways to leave a legacy for generations to come.

2. Life will instantly feel more precious.

Too much of a good thing decreases its value. Life is precious. It’s also temporary. Even when you’re young and healthy, your life could end unexpectedly at any time. Recognizing that life is fleeting helps us find joy and meaning in the small things—sunset and sunrise, a smile on your child’s face, a tree in the park—that sometimes get lost in the day-to-day. The people in your life can take on a new value because we realize that their lives are also temporary.

3. You’ll learn not to sweat the small stuff.

Thinking about our mortality can serve as inspiration to think more holistically about what it means to live our best life. In other words, it can move us to exercise and eat well because we only get one body. And at the same time, it’s an invaluable reminder that we only get one life, and we better enjoy it. So many of us are on a quest to find balance in our lives and define our own priorities. Remembering that we have this one life to live can help when weighing where we want to put our energy and attention.

Countless psychological studies have shown that a recognition of our own eventual ending can allow us to live a richer life—one filled with gratitude, presence of mind, and happiness. As you go through the checklist of factors contributing to your overall well-being—getting quality sleep, eating healthy food, exercising regularly, and sustaining meaningful relationships—make sure that forming a relationship with your own mortality is high on the list.

No one knew how important this practice was better than Apple’s Steve Jobs who, during his 2005 commencement speech at Stanford University, said, “Almost everything—all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure—these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important.”

If contemplating your mortality triggers fear, consider this.

Does thinking about our own death trigger fear? According to the 2017 Survey of American Fears conducted by Chapman University, 20.3% of Americans are “afraid” or “very afraid” of dying. While for some, fear of death is healthy as it makes us more cautious (such as wearing seat belts and minimizing high-risk behaviors), some people may also have an unhealthy fear of dying, which interferes with their daily life.

Psychologist and spirituality expert Stephen Taylor looked at those who lost loved ones, and many tend to have a more accepting attitude toward death. This may result from “post-traumatic growth,” or personal growth from trauma. Others suggest that much of our fear of death stems from not wanting to lose the things we’ve built up (i.e., relationships, possessions, or status). By letting go (even a little) of fierce attachments, it can allow for valuable shifts in perspective and benefits to our well-being.

My friend and colleague, B.J. Miller, M.D., puts this in a different light. “Death is not at odds with living. You can’t get one without the other.” Whether we like it or not, death is always present. Connecting to the fact that life is defined by the fact that it will end one day will allow you to live more fully, experience deeper relationships, and provide new meaning to your days.

Next time you have the opportunity to reflect on your mortality, think about how it might enrich your life today.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!