As with birth, dying is a process. How does it unfold? Can you prepare for it? And why should you keep talking to a dying person even if they don’t talk back?

We’re born, we live, we die. Few things are so concrete. And yet, while we swap countless stories about the start of life, the end is a subject we’re less inclined to talk about.

Conversations about death – what it is, what it looks like – are scarce until we suddenly face it head on, often for the first time with the loss of a loved one.

“We hold a lot of anxiety about what death means and I think that’s just part of the human experience,” says Associate Professor Mark Boughey, director of palliative medicine at Melbourne’s St Vincent’s Hospital. “Some people just really push it away and don’t think about it until it’s immediately in front of them.”

But it doesn’t need to be this way, he says.

“The more people engage and understand death and know where it’s heading … the better prepared the person is to be able to let go to the process, and the better prepared the family is to reconcile with it, for a more peaceful death.”

Of course, not everyone ends up in palliative care or even in a hospital. For some people, death can be shockingly sudden, as in an accident or from a cardiac arrest or massive stroke. Death can follow a brief decline, as with some cancers; or a prolonged one, as with frailty; or it can come after a series of serious episodes, such as heart failure. And different illnesses, such as dementia and cancer, can also cause particular symptoms prior to death.

But there are key physical processes that are commonly experienced by many people as they die – whether from “old age”, or indeed from cancer, or even following a major physical trauma.

What is the process of dying? How can you prepare for it? And how should you be with someone who is nearing the end of their life?

What are the earliest signs a person is going to die?

The point of no return, when a person begins deteriorating towards their final breath, can start weeks or months before someone dies.

Professor Boughey says refractory symptoms – stubborn and irreversible despite medical treatment – offer the earliest signs that the dying process is beginning: breathlessness, severe appetite and weight loss, fluid retention, fatigue, drowsiness, delirium, jaundice and nausea, and an overall drop in physical function.

Simple actions, such as going from a bed to a chair, can become exhausting. A dying person often starts to withdraw from the news, some activities and other people, to talk less or have trouble with conversation, and to sleep more.

This all ties in with a drop in energy levels caused by a deterioration in the body’s brain function and metabolic processes.

Predicting exactly when a person will die is, of course, nearly impossible and depends on factors ranging from the health issues they have to whether they are choosing to accept more medical interventions.

“The journey for everyone towards dying is so variable,” Professor Boughey says.

What happens in someone’s final days?

As the body continues to wind down, various other reflexes and functions will also slow. A dying person will become progressively more fatigued, their sleep-wake patterns more random, their coughing and swallowing reflexes slower. They will start to respond less to verbal commands and gentle touch.

Reduced blood flow to the brain or chemical imbalances can also cause a dying person to become disoriented, confused or detached from reality and time. Visions or hallucinations often come into play.

“A lot of people have hallucinations or dreams where they see loved ones,” Professor Boughey says. “It’s a real signal that, even if we can’t see they’re dying, they might be.”

But Professor Boughey says the hallucinations often help a person die more peacefully so it’s best not to “correct” them. “Visions, especially of long-gone loved ones, can be comforting.”

Instead of simply sleeping more, the person’s consciousness may begin to fluctuate, making them nearly impossible to wake at times, even when there is a lot of stimulation around them.

With the slowing in blood circulation, body temperature can begin to seesaw, so a person can be cool to the touch at one point and then hot later on.

Their senses of taste and smell diminish. “People become no longer interested in eating … they physically don’t want to,” Professor Boughey says.

This means urine and bowel movements become less frequent, and urine will be much darker than usual due to lower fluid intake. Some people might start to experience incontinence as muscles deteriorate but absorbent pads and sheets help minimise discomfort.

What happens when death is just hours or minutes away?

As death nears, it’s very common for a person’s breathing to change, sometimes slowing, other times speeding up or becoming noisy and shallow. The changes are triggered by reduction in blood flow, and they’re not painful.

Some people will experience a gurgle-like “death rattle”. “It’s really some secretions sitting in the back of the throat, and the body can no longer shift them,” Professor Boughey says.

An irregular breathing pattern known as Cheyne-Stokes is also often seen in people approaching death: taking one or several breaths followed by a long pause with no breathing at all, then another breath.

“It doesn’t happen to everybody, but it happens in the last hours of life and indicates dying is really front and centre. It usually happens when someone is profoundly unconscious,” Professor Boughey says.

Restlessness affects nearly half of all people who are dying. “The confusion [experienced earlier] can cause restlessness right at the end of life,” Professor Boughey says. “It’s just the natural physiology, the brain is trying to keep functioning.”

Circulation changes also mean a person’s heartbeat becomes fainter while their skin can become mottled or pale grey-blue, particularly on the knees, feet and hands.

Professor Boughey says more perspiration or clamminess may be present, and a person’s eyes can begin to tear or appear glazed over.

Gradually, the person drifts in and out or slips into complete unconsciousness.

How long does dying take? Is it painful?

UNSW Professor of Intensive Care Ken Hillman says when he is treating someone who is going to die, one of the first questions he is inevitably asked is how long the person has to live.

“That is such a difficult question to answer with accuracy. I always put a rider at the end saying it’s unpredictable,” he says.

“Even when we stop treatment, the body can draw on reserves we didn’t know it had. They might live another day, or two days, or two weeks. All we know is, in long-term speaking, they certainly are going to die very soon.”

But he stresses that most expected deaths are not painful. “You gradually become confused, you lose your level of consciousness, and you fade away.”

Should there be any pain, it is relieved with medications such as morphine, which do not interfere with natural dying processes.

“If there is any sign of pain or discomfort, we would always reassure relatives and carers that they will die with dignity, that we don’t stop caring, that we know how to treat it and we continue treatment.”

Professor Boughey agrees, saying the pain instead tends to sit with the loved ones.

“For a dying person there can be a real sense of readiness, like they’re in this safe cocoon, in the last day or two of life.”

Professor Boughey believes there is an element of “letting go” to death.

“We see situations where people seem to hang on for certain things to occur, or to see somebody significant, which then allows them to let go,” he says.

“I’ve seen someone talk to a sibling overseas and then they put the phone down and die.”

How can you ‘prepare’ for death?

Firstly, there is your frame of mind. In thinking about death, it helps to compare it to birth, Professor Boughey says.

“The time of dying is like birth, it can happen over a day or two, but it’s actually the time leading up to it that is the most critical part of the equation,” he says.

With birth, what happens in the nine months leading to the day a baby is born – from the doctor’s appointments to the birth classes – can make a huge difference. And Professor Boughey says it’s “absolutely similar” when someone is facing the end of life.

To Professor Hillman, better understanding the dying process can help us stop treating death as a medical problem to be fixed, and instead as an inevitability that should be as comfortable and peaceful as possible.

Then there are some practicalities to discuss. Seventy per cent of Australians would prefer to die at home but, according to a 2018 Productivity Commission report, less than 10 per cent do. Instead, about half die in hospitals, ending up there because of an illness triggered by disease or age-related frailty (a small percentage die in accident and emergency departments). Another third die in residential aged care, according to data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Professor Hillman believes death is over-medicalised, particularly in old age, and he urges families to acknowledge when a loved one is dying and to discuss their wishes: where they want to die, whether they want medical interventions, what they don’t want to happen.

“[Discussing this] can empower people to make their own decisions about how they die,” says Professor Hillman.

Palliative Care Nurses Australia president Jane Phillips says someone’s end-of-life preferences should be understood early but also revisited throughout the dying process as things can change. With the right support systems in place, dying at home can be an option.

“People are not being asked enough where they want to be cared for and where they want to die,” Professor Phillips says. “One of the most important things for families and patients is to have conversations about what their care preferences are.”

How can you help a loved one in their final hours?

Studies show that hearing is the last sense to fade, so people are urged to keep talking calmly and reassuringly to a dying person as it can bring great comfort even if they do not appear to be responding.

“Many people will be unconscious, not able to be roused – but be mindful they can still hear,” Professor Phillips says.

“As a nurse caring for the person, I let them know when I’m there, when I’m about to touch them, I keep talking to them. And I would advise the same to the family as well.”

On his ICU ward, Professor Hillman encourages relatives to “not be afraid of the person on all these machines”.

“Sit next to them, hold their hands, stroke their forehead, talk to them about their garden and pets and assume they are listening,” he says.

Remember that while the physical or mental changes can be distressing to observe, they’re not generally troubling for the person dying. Once families accept this, they can focus on being with their dying loved one.

Professor Boughey says people should think about how the person would habitually like them to act.

“What would you normally do when you’re caring for your loved one? If you like to hold and touch and communicate, do what you would normally do,” he says.

Other things that can comfort a dying person are playing their favourite music, sharing memories, moistening their mouth if it becomes dry, covering them with light blankets if they get cold or damp cloths if they feel hot, keeping the room air fresh, repositioning pillows if they get uncomfortable and gently massaging them. These gestures are simple but their significance should not be underestimated.

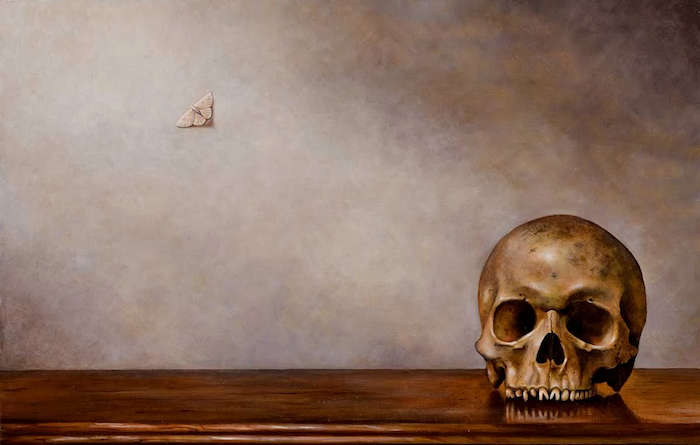

What is the moment of death?

In Australia, the moment of death is defined as when either blood circulation or brain function irreversibly cease in a person. Both will eventually happen when someone dies, it’s just a matter of what happens first.

Brain death is less common, and occurs after the brain has been so badly damaged that it swells, cutting off blood flow, and permanently stops, for example following a head injury or a stroke.

The more widespread type of death is circulatory death, where the heart comes to a standstill.

After circulation ceases, the brain then becomes deprived of oxygenated blood and stops functioning.

The precise time it takes for this to happen depends on an individual’s prior condition, says intensive care specialist Dr Matthew Anstey, a clinical senior lecturer at University of Western Australia.

“Let’s say you start slowly getting worse and worse, where your blood pressure is gradually falling before it stops, in that situation your brain is vulnerable already [from reduced blood flow], so it won’t take much to stop the brain,” Dr Anstey says.

“But if it’s a sudden cardiac arrest, the brain could go on a bit longer. It can take a minute or two minutes for brain cells to die when they have no blood flow.”

This means, on some level, the brain remains momentarily active after a circulatory death. And while research in this space is ongoing, Dr Anstey does not believe people would be conscious at this point.

“There is a difference between consciousness and some degree of cellular function,” he says. “I think consciousness is a very complicated higher-order function.”

Cells in other organs – such as the liver and kidneys – are comparatively more resilient and can survive longer without oxygen, Dr Anstey says. This is essential for organ donation, as the organs can remain viable hours after death.

In a palliative care setting, Professor Boughey says the brain usually becomes inactive around the same time as the heart.

But he says that, ultimately, it is the brain’s gradual switching off of various processes – including breathing and circulation – that leads to most deaths.

“Your whole metabolic system is run out of the brain… [It is] directing everything.”

He says it’s why sometimes, just before death, a person can snap into a moment of clarity where they say something to their family. “It can be very profound … it’s like the brain trying one more time.”

What does a dead person look like?

“There is a perceptible change between the living and dying,” Professor Boughey says.

“Often people are watching the breathing and don’t see it. But there is this change where the body no longer is in the presence of the living. It’s still, its colour changes. Things just stop. And it’s usually very, very gentle. It’s not dramatic. I reassure families of that beforehand.”

A typical sign that death has just happened, apart from an absence of breathing and heartbeat, is fixed pupils, which indicate no brain activity. A person’s eyelids may also be half-open, their skin may be pale and waxy-looking, and their mouth may fall open as the jaw relaxes.

Professor Boughey says that only very occasionally will there be an unpleasant occurrence, such as a person vomiting or releasing their bowels but, in most cases, death is peaceful.

And while most loved ones want to be present when death occurs, Professor Boughey says it’s important not to feel guilty if you’re not because it can sometimes happen very suddenly. What’s more important is being present during the lead-up.

What happens next?

Once a person dies, a medical professional must verify the death and sign a certificate confirming it.

“It’s absolutely critical for the family to see … because it signals very clearly the person has died,” says Professor Boughey. “The family may not have started grieving until that point.”

In some cases, organ and tissue donation occurs, but only if the person is eligible and wished to do so. The complexity of the process means it usually only happens out of an intensive care ward.

Professor Boughey stresses that an expected death is not an emergency – police and paramedics don’t need to be called.

After the doctor’s certificate is issued, a funeral company takes the dead person into their care and collects the information needed to register the death. They can also help with newspaper notices or flowers.

But all of this does not need to happen right away, Professor Boughey says. Do what feels right. The moments after death can be tranquil, and you may just want to sit with the person. Or you might want to call others to come, or fulfil cultural wishes.

“There is no reason to take the body away suddenly,” Professor Boughey says.

You might feel despair, you might feel numb, you might feel relief. There is no right or wrong way to feel. As loved ones move through the grieving process, they are reminded support is available – be it from friends, family or health professionals.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!