By Ellen Shehadeh

Dr. Steve Hadland began his medical career as an emergency room physician, fixing people and saving lives at all costs. These days he treasures his work as a hospice physician associated with Hospice of Petaluma, tending to the terminally ill and allowing them to die in comfort. Two extremes, one might say, but understandable given the intervening events in his life.

Steve’s practice melds a deep belief in social justice, reverence for life in all forms and enduring, self-described conservative views about end-of-life practices. His youthful face and genial manner, combined with an easy laugh and a soothing voice, belie the depth of his thinking, intellect and perceptions. He is informed not only by medical writings but also by psychology, literature, philosophy and classical music. One feels both calm and welcome in his presence.

Steve was the youngest in a conservative family growing up in Chicago. He attended university in Iowa City, studying astrophysics as a stepping stone to an astronaut program, and later majored in neuroscience. “University was a political and social awakening, as well as an intellectual one,” he says. He participated in marches and protests against the Vietnam War and for civil rights.

He longed to break out even further from his roots, however, and what better place than California, where “legend loomed for surfing and blondes.” He never quite managed the surfing thing, but wasted no time marrying his first wife, a blonde, during the summer of love, which coincided with his first year at Stanford Medical School. Their marriage of seven years included major involvements in the civil rights, anti-war and human potential movements.

All along, he had thoughts and profound feelings about end-of-life experiences, in part influenced by a Tolstoy novella, “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” which he read in a death and dying course at Stanford. “It inspired me then, and continues to inspire me, year after year,” he says of the book, which he recommends “to anyone who really wants to know about what it’s like to die.”

Steve’s first job out of medical school, in 1972, was in a Kaiser emergency room. The nurses recognized his empathic nature and would steer the most difficult patients his way. Yet he recoiled at the Herculean efforts by staff to revive a dying patient, “all the excitement, the IVs,” and how quickly and “disrespectfully” staff abandoned a corpse when resuscitation efforts failed. At the time, there was no such thing as “do not resuscitate” or hospice.

Steve sought a different kind of medical experience and, in the fall of 1974, he arranged an interview with Dr. Michael Whitt in Point Reyes Station. He remembered the area from a drive many years before; “It cast a spell on me,” he says. Dr. Whitt’s liberal medical practice included home births, which at the time were popular in alternative communities, but Steve was stunned that he would deliver babies without liability insurance.

Steve’s conservative orientation and lack of maturity led him to decline a job offer by Dr. Whitt but, many years later, he would run a small integrative medical practice and pain management clinic out of his Point Reyes Station home. Ironically, he never secured liability insurance. “The influence of West Marin,” he quips.

Newly divorced in 1978, Steve encountered a single mother of three from Holland who was working as a Kaiser receptionist to pay her way through nursing school. They married two years later and, after 38 years, “it looks like it’s going the distance,” he says, laughing. Anneke van der Veen became an emergency room nurse, but they never worked together professionally, realizing the potential pitfalls of mixing business with pleasure.

Steve had traveled to England in 1978 to visit the first modern hospice. Although he was impressed with the approach, “I could tell I wasn’t ready for it,” he says. It was 12 years later that he helped start a hospice in Santa Clara, which he ran for five years along with an oncologist friend. He explains: “The world said, ‘You seem to be ready.’”

As society’s views about death and dying dramatically changed over the years, so clearly have Steve’s. Fifty years ago, death was a taboo subject and doctors rarely broached it with their terminal patients or even gave them an honest diagnosis. Now people take advantage of many choices, like refusing to eat and drink or using lethal medications now sanctioned by law. In California, the End of Life Option Act allows a patient to self-administer a lethal cocktail, but only after being judged by two physicians to be of sound mind and six months from death.

Some people object to the strictness of this law, which does not allow someone to assist in a patient’s suicide if the patient is physically or mentally unable to self-administer, even if it had been the patient’s expressed wish. In some states such assistance could be considered euthanasia or even murder.

Steve agrees with this self-described conservative view. “I don’t think it’s a bad thing; we don’t know what’s going on [inside their head]” or what kind of life these patients, some with Alzheimer’s and dementia, might have that we cannot fathom, he says. Surprisingly for a hospice worker, he was still opposed to the law when it was passed in July 2017, because “it’s a slippery slope.” How slippery? He cites a law in the Netherlands that now allows not only terminally ill patients but also depressed people to legally receive the fatal cocktail.

Steve explained that under California law, doctors may not legally list the cause of death as suicide when a patient has taken his or her own life. But the law “does allow a reference to the use of aid-in-dying meds as a contributing factor in the death, including the underlying fatal illness.” Steve, as a personal practice, does not include aid-in-dying medicines on the death certificate “to protect the patient from any backlash involving the choice of an induced death.”

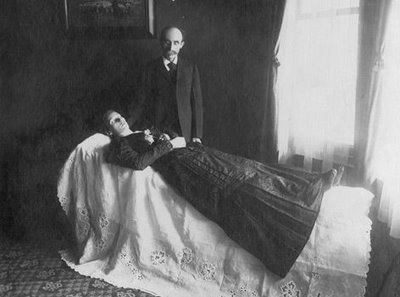

Today Steve appreciates what he calls the “majesty and mystery” of death. Along with survivors, he participates in ancient rituals—“beautiful ceremonies” like washing and dressing the body—and finds it deeply humbling.

Steve is a spiritual man. He is influenced by the teachings of Jean Klein, a European who had an awakening in India. Although it is difficult to summarize Klein’s ideas, one important teaching is, “I am not identical with my thought process.” Steve believes that most of what one knows can be understood through other means, “coming from the heart and a sense of pure being.” This understanding has given him confidence to communicate with a dying person without words. “There is something in me that I know will make a difference. I am not anxious or worried, and am not in my head,” he explains.

About society’s recent openness to discussing death and dying, Steve cannot be more positive. It used to be, “If I don’t talk about it, it won’t happen.” The effect of the hospice movement has been to “lift the lid about frank, open discussions about death and dying. It helps people plan and frees them from living in a false reality, or a web of lies,” he says.

Naturally, one so intimate with death has opinions and thoughts about what awaits us all in the end. And what is the best death, to go quickly or to linger for a while? Not surprisingly, Steve believes that for himself, the ideal death would be when you know it is coming. “You get to finish your life, and say your goodbyes,” he says.

Steve also believes in a “continuity of consciousness.” This idea came to him intuitively years ago, after the death of his beloved dog, Misha, whose picture is prominently displayed on his office wall among other family photos. He tells this story, choking back tears.

“As I stood over the grave, I called out loud, ‘Where have you gone?’

A small voice inside asked, ‘Did you love me?’

‘Yes.’ ‘Do you still love me?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then that’s where I am.’”

Steve says, “My co-workers, patients and families living with the experience of dying have taught me much of what I know about love. Not the romantic love, of course, but something more encompassing, a feeling of compassion and connection with others that grows into this deep feeling of commonality and love.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!