By Sarah Moss

Creative and emotionally healthy funerals are making waves in communities that value personal choices, resourcefulness and good old wholesome naturalness, but for reasons of expense they also appeal to blue collar workers.

A rejuvenated fire station in Port Kembla, cradled between the Illawarra region’s industrial centre and the sea, is home to Tender Funerals: the first not-for-profit funeral service in Australia.

Ashleigh Martin is a part-time director at the parlour.

“We’re about empowering families to make the choices they need to make to have a beautiful funeral,” she said.

“There’s definitely a need in our community for people to be able to have affordable funerals that are authentic.”

Since its inception in 2016, the community-run organisation has guided over 300 families and loved ones through their losses.

The parlour offers a multitude of services that assist people to have memorable personalised ceremonies, the latest trend in the industry is bio-degradable woven wicker coffins, handmade in the Byron Shire.

Dignity in death

The not-for-profit is changing the way communities look at death and dying, empowering families to make the choices they need to make, to have a beautiful funeral.

Founder Jenny Briscoe-Hough previously worked in the death industry for

many years and conceived a new business model by combining funerals with music and art.

The model looks at affordability and encourages people to “own” the experience, to take back their power in the face of death.

“We empower and guide people to have a meaningful, beautiful, send off,” Ms Martin said.

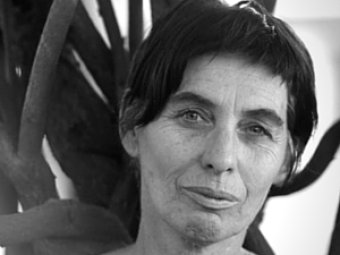

Malika Elizabeth is a local musician whose involvement with the establishment extends to directing and singing in the organisation’s community choir, and acting occasionally as a celebrant.

“She’s a visionary when it comes to community and bringing people together,” Ms Elizabeth said.

“She’s created a space for people just to be with each other, to be with their emotions, and to join together in commonality.”

Grassroots ethos

Unlike wooden or cardboard caskets, the woven caskets offered at Tender Funerals are perfect for hand-decorating with ribbons and other personalised items.

“They [clients] just want something unique and different that they can personalise as well by putting flowers on it or weaving through it,” Ms Martin said.

“We know if it is getting buried that it will break down quickly and won’t leach any harmful chemicals into the earth.”

After working in traditional for-profit homes, Ms Martin said that at Tender Funerals it is not about upselling to grieving families.

“It’s very much about thinking about what we can do differently and what we can do to give meaningful tokens back to our families,” she said.

Art for health’s sake

The grassroots ethos is intertwined through every detail of the business, from the handmade and decorated wicker caskets to a fortnightly community sewing circle run by the group.

Tender’s artist-in-residence Michell Elliot illuminates the cyclical nature of life and death with those in grief using muslin and donated funeral flowers.

The colourful cloth she creates is then used as shrouds for bodies, encouraging creative expression to farewell loved ones.

“I think that if clients choose to shroud somebody with one of our tender cloths that it’s done with love, and I think that’s a really beautiful thing,” Ms Martin said.

Ms Elliot also assists in providing a safe space program at the parlour for people to come together, grieve, share stories and sew.

The parlour facilitates a safe meditative space created through the arts for people to connect with their emotions to heal.

“When people feel that maybe they don’t want to see their loved ones being prepared for burial, or they don’t know what to do, how to feel, just sitting and sewing quietly allows those feelings to come, to be processed and to shift and move,” Ms Elliot said.

Music, art and funerals naturally go together

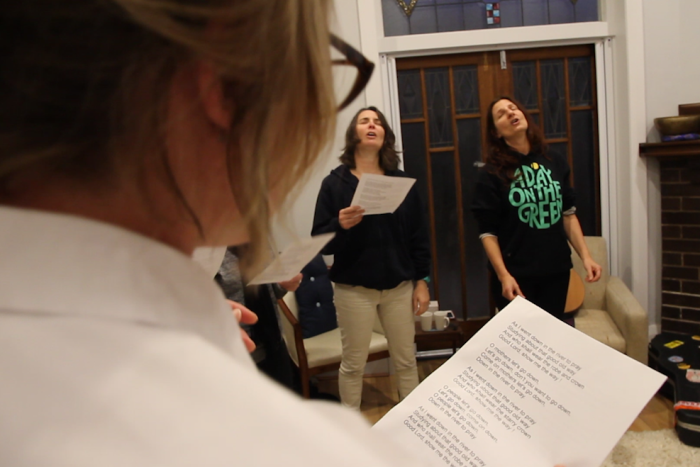

The organisation is also home to an in-house choir.

On Thursday evenings at the old fire station, people come together to sing songs of life, songs of death and songs of love.

Choir directors Jodi Phillis and Malika Elizabeth have sung at grave sides, in memorial services and during intimate preparation times.

They said they feel honoured to be at every funeral they attend.

“These elements go together naturally with us because we are musical people, but I think in a community like Port Kembla, where people just aren’t aware that this stuff can actually be available to them, it might be something people just don’t think of,” Ms Phillis said.

“That they can have live music to celebrate the life of the loved one they lost.

According to Ms Phillis the business model adopted by Tender Funerals relies on two fundamental aspects.

“One, to bring the sacred power of music and art into the community, especially for people who aren’t religious but still want to celebrate the life of the deceased,” she said.

“The other really strong element is supporting the arts.”

Selecting the soundtrack for a particular event can be a collaborative experience.

“Generally, families will have an idea of what music will be best for their loved one, but sometimes we make suggestions,” Ms Phillis said.

“It’s kind of whatever works really.”

“We all have the feeling that music is a spiritual thing,” Ms Phillis said.

“It comes out of us, it’s linked with the heavens, it’s what fills in the gap in the air.

“If anything is going to reach our loved one, it’s going to be music.”

At this point in time Tender’s business model is focussed on the Port Kembla premises, but having survived two years of operations, their success indicates a community movement towards an organic, not-for-profit model, with plans to expand.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

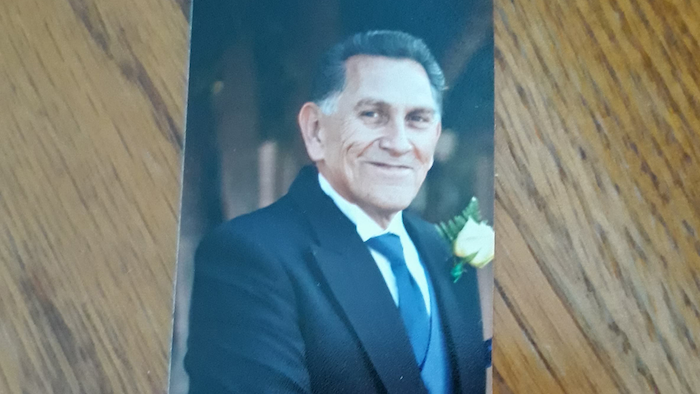

John, a Purple Heart–decorated World War II vet, had never been sick. Only in recent months had he developed some mild high blood pressure, for which his internist had prescribed chlorthalidone, a weak diuretic. Otherwise, his only medicine over the years was a preventive baby aspirin every day. With some convincing he agreed to be seen, so along with his wife and mine, we drove over to the local ER. The doctor there thought he might have had some kind of stroke, but a head CT didn’t show any abnormality. But then the bloodwork came back and showed, surprisingly, a critically low potassium level of 1.9 mEq/L—one of the lowest I’ve seen. It didn’t seem that the diuretic alone, which can cause less extreme reduction in potassium, could be the culprit. Nevertheless, John was admitted overnight just to get his potassium level restored by intravenous and oral supplement.

John, a Purple Heart–decorated World War II vet, had never been sick. Only in recent months had he developed some mild high blood pressure, for which his internist had prescribed chlorthalidone, a weak diuretic. Otherwise, his only medicine over the years was a preventive baby aspirin every day. With some convincing he agreed to be seen, so along with his wife and mine, we drove over to the local ER. The doctor there thought he might have had some kind of stroke, but a head CT didn’t show any abnormality. But then the bloodwork came back and showed, surprisingly, a critically low potassium level of 1.9 mEq/L—one of the lowest I’ve seen. It didn’t seem that the diuretic alone, which can cause less extreme reduction in potassium, could be the culprit. Nevertheless, John was admitted overnight just to get his potassium level restored by intravenous and oral supplement.