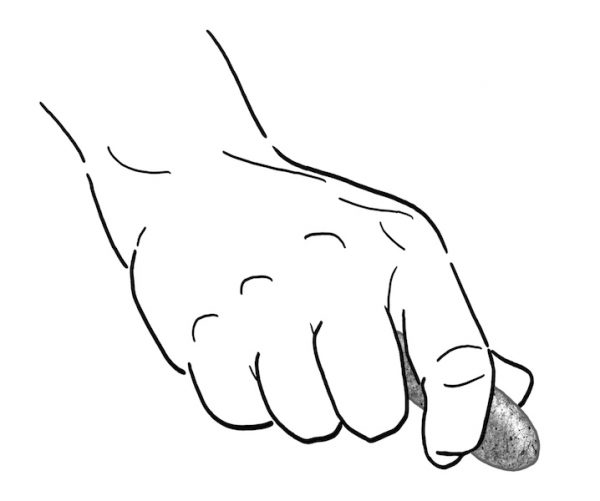

[H]umans may have ritualistically “killed” objects to remove their symbolic power, some 5,000 years earlier than previously thought, a new international study of marine pebble tools from an Upper Paleolithic burial site in Italy suggests.

Researchers at Université de Montréal, Arizona State University and University of Genoa examined 29 pebble fragments recovered in the Caverna delle Arene Candide on the Mediterranean Sea in Liguria. In their study, published online Jan. 18 in the Cambridge Archeological Journal, they concluded that some 12,000 years ago the flat, oblong pebbles were brought up from the beach, used as spatulas to apply ochre paste to decorate the dead, then broken and discarded.

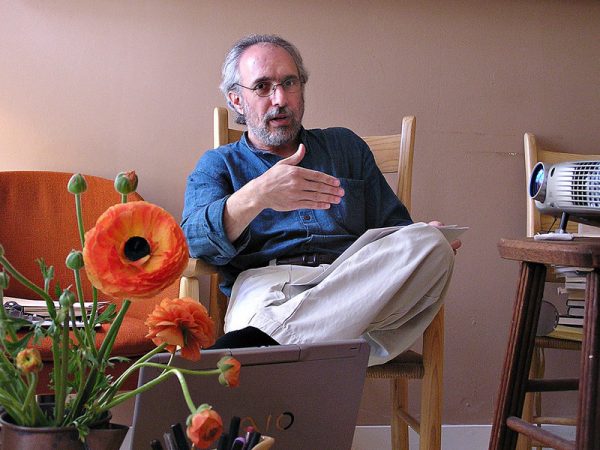

The intent could have been to “kill” the tools, thereby “discharging them of their symbolic power” as objects that had come into contact with the deceased, said the study’s co-author Julien Riel-Salvatore, an associate professor of anthropology at UdeM who directed the excavations at the site that yielded the pebbles.

The Arene Candide is a hockey-rink-sized cave containing a necropolis of some 20 adults and children. It is located about 90 metres above the sea in a steep cliff overlooking a limestone quarry. First excavated extensively in the 1940s, the cave is considered a reference site for the Neolithic and Paleolithic periods in the western Mediterranean. Until now, however, no one had looked at the broken pebbles.

“If our interpretation is correct, we’ve pushed back the earliest evidence of intentional fragmentation of objects in a ritual context by up to 5,000 years,” said the study’s lead author Claudine Gravel-Miguel, a PhD candidate at Arizona State’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change, in Tempe. “The next oldest evidence dates to the Neolithic period in Central Europe, about 8,000 years ago. Ours date to somewhere between 11,000 and 13,000 years ago, when people in Liguria were still hunter-gatherers.”

No matching pieces to the broken pebbles were found, prompting the researchers to hypothesize that the missing halves were kept as talismans or souvenirs. “They might have signified a link to the deceased, in the same way that people today might share pieces of a friendship trinket, or place an object in the grave of a loved one,” Riel-Salvatore said. “It’s the same kind of emotional connection.”

Between 2008 and 2013, the researchers painstakingly excavated in the Arene Candide cave immediately east of the original excavation using small trowels and dental tools, then carried out microscopic analysis of the pebbles they found there. They also scoured nearby beaches in search of similar-looking pebbles, and broke them to see if they compared to the others, trying to determine whether they had been deliberately broken.

“This demonstrates the underappreciated interpretive potential of broken pieces,” the new study concludes. “Research programs on Paleolithic interments should not limit themselves to the burials themselves, but also explicitly target material recovered from nearby deposits, since, as we have shown here, artifacts as simple as broken rocks can sometimes help us uncover new practices in prehistoric funerary canons.”

The findings could have implications for research at other Paleolithic sites where ochre-painted pebbles have been found, such as the Azilian sites in the Pyrenee mountains of northern Spain and southern France. Broken pebbles recovered during excavations often go unexamined, so it might be worth going back and taking a second look, said Riel-Salvatore.

“Historically, archeologists haven’t really looked at these objects – if they see them at a site, they usually go ‘Oh, there’s an ordinary pebble,’ and then discard it with the rest of the sediment,” he said. “We need to start paying attention to these things that are often just labeled as rocks. Something that looks like it might be natural might actually have important artifactual meaning.”

Complete Article HERE!