— just in time for a death boom

By Karen Heller

Dayna West knows how to throw a fabulous memorial shindig. She hired Los Angeles celebration-of-life planner Alison Bossert — yes, those now exist — to create what West dubbed “Memorialpalooza” for her father, Howard, in 2016 a few months after his death.

“None of us is going to get out of this alive,” says Bossert, who helms Final Bow Productions. “We can’t control how or when we die, but we can say how we want to be remembered.”

And how Howard was remembered! There was a crowd of more than 300 on the Sony Pictures Studios. A hot-dog cart from the famed L.A. stand Pink’s. Gift bags, the hit being a baseball cap inscribed with “Life’s not fair, get over it” (a beloved Howardism). A constellation of speakers, with Jerry Seinfeld as the closer (Howard was his personal manager). And babka (a tribute to a favorite “Seinfeld” episode).

“My dad never followed rules,” says West, 56, a Bay Area clinical psychologist. So why would his memorial service

Death is a given, but not the time-honored rituals. An increasingly secular, nomadic and casual America is shredding the rules about how to commemorate death, and it’s not just among the wealthy and famous. Somber, embalmed-body funerals, with their $9,000 industry average price tag, are, for many families, a relic. Instead, end-of-life ceremonies are being personalized: golf-course cocktail send-offs, backyard potluck memorials, more Sinatra and Clapton, less “Ave Maria,” more Hawaiian shirts, fewer dark suits. Families want to put the “fun” in funerals

The movement will only accelerate as the nation approaches a historic spike in deaths. Baby boomers, despite strenuous efforts to stall the aging process, are not getting any younger. In 2030, people over 65 will outnumber children, and by 2037, 3.6 million people are projected to die in the United States, according to the Census Bureau, 1 million more than in 2015, which is projected to outpace the growth of the overall population

Just as nuptials have been transformed — who held destination weddings in the ’90s? — and gender-reveal celebrations have become theatrical productions, the death industry has experienced seismic changes over the past couple of decades. Practices began to shift during the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, when many funeral homes were unable to meet the needs of so many young men dying, and friends often hosted events that resembled parties.

Now, many families are replacing funerals (where the body is present) with memorial services (where the body is not). Religious burial requirements are less a consideration in a country where only 36 percent of Americans say they regularly attend religious services, nearly a third never or rarely attend, and almost a quarter identify as agnostic or atheist, according to the Pew Research Center.

Funeral homes adapt

More than half of all American deaths lead to cremations, compared to 28 percent in 2002, due to expense (they can cost a third the price of a burial), the environment, and family members living far apart with less ability to visit cemetery plots, according to the National Funeral Directors Association. By 2035, the cremation rate is projected to be a staggering 80 percent, the association says. And cremation frees loved ones to stage a memorial anywhere, at any time, and to store or scatter ashes as they please. (Maintenance of cemeteries, if families stop using them, may become a preservation and financial problem

Past funeral association president Mark Musgrove, who runs a network of funeral homes and chapels in Eugene, Ore., says his industry, already marked by consolidation, is adapting to changing demands.

“Services are more life-centered, around the person’s personality, likes and dislikes. They’re unique and not standardized,” he says. “The only way we can survive is to provide the services that families find meaningful.”

Funeral homes have hired event planners, remodeled drab parlors to include dance floors and lounge areas, acquired liquor licenses to replace the traditional vat of industrial-strength coffee. In Oregon, where cremation rates are near 80 percent, Musgrove has organized memorial celebrations at golf courses and Autzen Stadium, home of the Ducks. He sells urns that resemble giant golf balls and styles adorned with the University of Oregon logo. In a cemetery, his firm installed a “Peace Columbarium,” a retrofitted 1970s VW van, brightly painted with “Peace” and “Love,” to house urns.

Change has sparked nascent death-related industries in a culture long besotted with youth. There are death doulas (caring for the terminally ill), death cafes (to discuss life’s last chapter over cake and tea), death celebrants (officiants who lead end-of-life events), living funerals (attended by the honored while still breathing), and end-of-life workshops (for the healthy who think ahead). The Internet allows lives to continue indefinitely in memorial Facebook pages, tribute vlogs on YouTube and instamemorials on Instagram.

Memorials are no longer strictly local events. As with weddings and birthdays, families are choosing favorite vacation idylls as final resting spots. Captain Ken Middleton’s Hawaii Ash Scatterings performs 600 cremains dispersals a year for as many as 80 passengers on cruises that may feature a ukulele player, a conch-shell blower and releases of white doves or monarch butterflies.

“It makes it a celebration of life and not such a morbid affair,” says Middleton. His service is experiencing annual growth of 15 to 20 percent.

From coffins to compost

With increased concern for the environment, people are opting for green funerals, where the body is placed in a biodegradable coffin or shroud.

The industry is literally thinking outside the box.

“My work is letting people connect with the natural cycle as they die,” says Katrina Spade of Recompose in Seattle, who considers herself part of the “alternative death-care movement.” If its legislature grants approval this month, Washington will become the first state in the nation to approve legalized human composting. Her company plans to use wood chips, alfalfa and straw to turn bodies into a cubic yard of top soil in 30 days. That soil could be used to fertilize a garden, or a grove of trees, the body literally returned to the earth.

Spade questions why death should be a one-event moment, rather than an opportunity to create an enduring tradition, a deathday, to honor the deceased: “I want to force my family to choose a ritual that they do every year.”

Death has inspired Etsy-like enterprises that transform a loved one’s ashes into vinyl, “diamonds,” jewelry and tattoos. Ashes to ashes, dust to art.

After Seattle artist Briar Bates died in 2017 at age 42, four dozen friends performed her joyous water ballet in a public wading pool, “a fantastic incarnation of Briar’s spirit,” says friend Carey Christie. “Anything other than denial that you’re going to die is a healthy step in our culture.”

Funeral consultant Elizabeth Meyer wrote the memoir “Good Mourning” and named her website Funeral Guru Liz. Her motto: “Bringing Death to Life.” She notes, “Most people do not plan. What’s changing is more people are talking about it, and the openness of the conversation. Our world will be a better place when people let their wishes be known.”

In 2012, Amy Pickard’s mother “died out of the blue.” She was unprepared but also transformed. Now, she’s “the death girl,” an advocate for the “death-positive movement,” sporting a “Life is a near-death experience” T-shirt, teaching people how to plan by hosting monthly Good to Go parties in Los Angeles and offering a $60 “Departure File,” 50 pages to address almost every need.

“We’re still in the really early days of super-creative funerals. There’s this censorship of death and grief,” Pickard says. “You have the rest of your life to be sad over the person who died. The hope is to celebrate their time on Earth and who they were.”

Overshadowing grief?

Some practitioners worry that death has taken a holiday, and grief is too frequently banished in end-of-life celebrations that seem like birthday blowouts.

“Do you think we’re getting too happy with this?” asks Amy Cunningham, director of the Inspired Funeral in Brooklyn. “You can’t pay tribute to someone who has died without acknowledging the death and sadness around it. You still have to dip into reality and not ignore the fact that they’re absent now

But even sadness is being treated differently. In some services, instead of offering hollow platitudes that barely relate to the deceased, “we are getting a new radical honesty where people are openly talking about alcoholism, drug use and the tough times the person experienced,” Cunningham says. Suicide, long hidden, appears more in obituaries; opioid addiction, especially, is addressed in services.

West, who hosted such a memorable send-off for her father, has some plans for her own: “Great food and live music, preferably Latin-inspired,” and “my personal possessions are auctioned off,” the proceeds benefiting a children’s charity. Why can’t a memorial serve as a fundraiser?

An avid traveler, West plans to designate friends to disperse her cremains in multiple locations “that have significance in my life” and leave funds to subsidize those trips — a global, destination ash-scattering.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

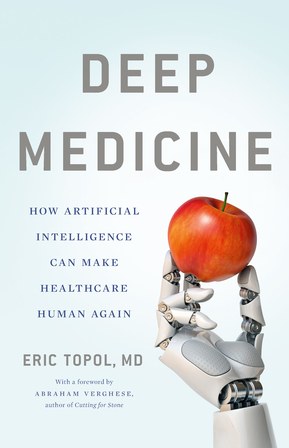

John, a Purple Heart–decorated World War II vet, had never been sick. Only in recent months had he developed some mild high blood pressure, for which his internist had prescribed chlorthalidone, a weak diuretic. Otherwise, his only medicine over the years was a preventive baby aspirin every day. With some convincing he agreed to be seen, so along with his wife and mine, we drove over to the local ER. The doctor there thought he might have had some kind of stroke, but a head CT didn’t show any abnormality. But then the bloodwork came back and showed, surprisingly, a critically low potassium level of 1.9 mEq/L—one of the lowest I’ve seen. It didn’t seem that the diuretic alone, which can cause less extreme reduction in potassium, could be the culprit. Nevertheless, John was admitted overnight just to get his potassium level restored by intravenous and oral supplement.

John, a Purple Heart–decorated World War II vet, had never been sick. Only in recent months had he developed some mild high blood pressure, for which his internist had prescribed chlorthalidone, a weak diuretic. Otherwise, his only medicine over the years was a preventive baby aspirin every day. With some convincing he agreed to be seen, so along with his wife and mine, we drove over to the local ER. The doctor there thought he might have had some kind of stroke, but a head CT didn’t show any abnormality. But then the bloodwork came back and showed, surprisingly, a critically low potassium level of 1.9 mEq/L—one of the lowest I’ve seen. It didn’t seem that the diuretic alone, which can cause less extreme reduction in potassium, could be the culprit. Nevertheless, John was admitted overnight just to get his potassium level restored by intravenous and oral supplement.