Women had few powers in Ancient Greece – except in death.

Demonstrating grief through wailing and song has long been a historic, sacred part of honouring and remembering the dead. From the Chinese to the Assyrians, Irish and Ancient Greeks, oral rituals of outward mourning were a responsibility that fell (and continue to fall) to women.

In Ancient Greece, while women may have lacked political and social freedom, the realm of mourning belonged to them. Their role in remembering the dead granted them their only position of power in a society where they possessed no autonomy. Yet this power was also believed to supersede mortal constraints, giving women the ability to do something that men could not.

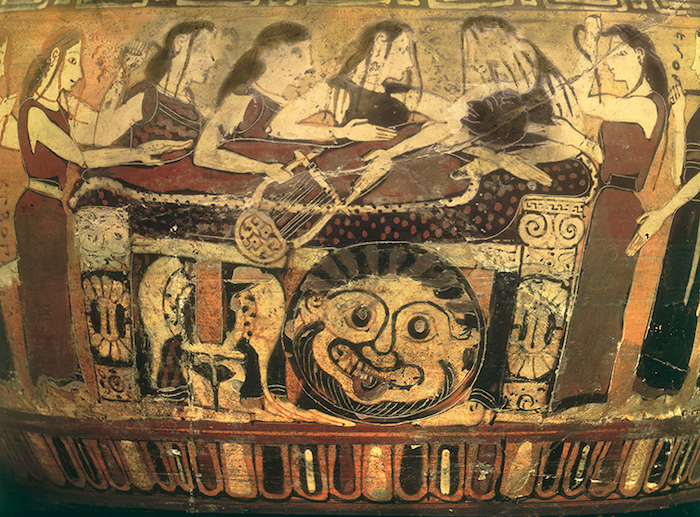

The Greek funeral was composed of three parts: the prothesis, or preparation and laying out of the body; the ekphora, or transportation to the place of burial; and the burial of the body or the entombment of cremated remains. It was during the prothesis that the women began their ritual of lament. First, they cleansed the corpse, anointed it and decorated it with aromatic garlands as it lay atop its kline (bier). Once the body was prepared, scores of female relatives gathered around it to beat their breasts and tear the hair from their scalps as they sang funeral songs. They wished to communicate the awful weight of their grief in order to satisfy the dead, whom they believed could hear and judge their cries. In contrast, the men kept their distance to salute the dead, physically signifying their separation from the realm that belonged to women. Some art from the Geometric period suggests they may have joined the female mourners in writhing to the lament, though they were spared from the excruciating gesture of ripping out their hair.

The funeral song served as an extension of the physical pain women inflicted upon themselves during the prothesis. Its purpose was to communicate a cry of uncontrollable pain, a hysteric melody that was believed to be rooted in feminine emotions; thus, only women could be the vessels for this pain. In the depths of their sorrow and self-torture, female mourners in the Geometric period would have sung a melody from one of the four major funeral song categories: threnos, epikedeion, ialemos or goos. These songs were personal and meaningful to the bereaved. In her book Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry (1979), which, through the art they have left behind, analyses how the Ancient Greeks viewed death, Emily Vermeule writes that goos was the most intense kind of funeral song. It might have been reserved for lovers or close family members, as its theme was centred on the relationship between two lives shared, the one now lost.

Leading the funeral lament was the song leader, also called the eksarkhos gooio, or the chief mourner. In early times, she was a professional mourner, but could also be the mother or close female relative of the dead. The song leader served as the liaison between those who mourned and those who had passed, guiding the bereaved through the proper course of remembrance in order to mollify the dead. As she led the female mourners in lament, she was careful to cradle the head of the corpse. Touch was necessary in order to open the ears of the dead. But once the ears were opened, the living women had to tread carefully. Not only could the dead hear funeral laments sung for them during the prothesis, they could also determine whether the presence of the living was good or malevolent. This is the reason, writes Robert Garland in The Greek Way of Death (1985), that Odysseus is advised against participating in Ajax’s funeral. Mourners entrusted their song leader with the responsibility of appeasing the dead to ensure their smooth transition into the spirit world.

As time went on, the role of female song leader would serve as the predecessor to an occult offshoot, the goes, who used song as a vehicle to transcend mortal constraints. Under the goes, funeral songs were no longer songs: they were spells, used to lure the dead back to earth. The goes was akin to a witch, due to her supernatural powers; she had even mastered the art of necromancy and could temporarily bring corpses back to life. Yet, even before the goes and the eksarkhos gooio, women in Ancient Greece had ties to the occult side of death. If the eksarkhos gooio was the mother of this occult tradition and the goes the maiden, the egkhystristriai was the crone. Before the classical period, the egkhystristriai was believed to have officiated at the burial of the body. Like an occult high priestess, her powers stemmed from the ritual of making blood sacrifices to the dead. Later, these sacrifices turned into the more modest ritual of offering libations, exemplified as Antigone pours offerings over her brother Polyneikes after she performs rites over his body.

By the fifth century BC mourning rituals had become less elaborate and deliberately reduced the importance of the female role. The number of female lamenters who surrounded the dead dwindled from scores of close relatives to only a few. Laments became more antiphonal and grew to involve men. Gestures such as tearing the hair were replaced by the symbolic gesture of cutting the hair short. These later changes suggest that the Greeks believed their dead were in less need of appeasement, eradicating the need for a song leader with supernatural inclinations. But they attempted to diminish the role that women had in the death process, thus dismantling a space in which women held dominance. In the classical period, women were relegated to the background of the funerary ritual, writes Maria Serena Mirto in Death in the Greek World (2012), because men feared it would threaten social cohesion and their desire for death to be pro patria, for one’s country. This is evident from Greek state funeral records, such as that in Kerameikos, the Athens cemetery, in which female lamenters are only briefly mentioned, suddenly peripheral to the ritual they had previously orchestrated.

The trend of removing women from the centre of death is not exclusive to Ancient Greece. While some cultures, such as the Assyrians, fought to preserve the role of female lamenters, others have been unable to do so.As Richard Fitzpatrick reported in the Irish Examiner in 2016, in Ireland, the tradition of female keeners, who wail in grief, began to die out in the mid-20th century. In the United States, male funeral directors replaced the long-standing tradition of female layers-out. Women were left behind, as the funeral directors attempted and succeeded at monetising the death industry, a legacy that continues to haunt the recently bereaved, who must deal with costly funeral arrangements.

Today, however, we find ourselves in the midst of a death renaissance, spearheaded by morticians, activists and artisans alike – a majority of whom are women. Ancient mourning rituals and traditions are resurging. Perhaps the role of the female song leader as a spiritual caster of spells will find its way back, too.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!