Arrives When It’s Needed Most

Courtney Bryan’s Requiem, premiering Thursday after its original date was canceled last year, now follows a time of loss and upheaval.

You’ve probably heard a story like this before. Courtney Bryan’s Requiem was set to premiere with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in late March 2020. In a time of incalculable loss, her music became part of another kind of casualty: the sounds that vanished from stages around the world.

Like many premieres originally planned for the past year, Bryan’s Requiem, written for the vocal quartet Quince Ensemble and members of the Chicago Symphony, was stranded in limbo. But through the orchestra’s turn to online programming and a season-ending series organized by Missy Mazzoli, its composer in residence, the piece was given a new date this week, when the latest episode of CSO Sessions lands on the streaming platform CSOtv.

Maybe it’s actually more fitting that the Requiem be released now, as the United States emerges from its worst days of the pandemic — over 600,000 deaths later — and the country celebrates its first federally recognized Juneteenth, a year after the emotional, nationwide peak of the Black Lives Matter movement following the murder of George Floyd.

“I think about the loss in my own life, but I know that a lot of people have had a lot of losses during this time, due to Covid and other situations,” Bryan said in a recent interview. “So I’m really happy that this is the actual premiere.”

Bryan, who is based in and from New Orleans, is a composer and performer who deals in collaboration, with an open ear to traditions like jazz and gospel — and, occasionally, to topics around racial justice like Black Lives Matter. In “Sanctum” (2015), she wove live orchestral playing in with sounds including the voices of demonstrators in Ferguson, Mo. Her oratorio “Yet Unheard” (2016) commemorated the life of Sandra Bland.

Her Requiem was meant to be more abstract — haunted by contemporary tragedies, perhaps, but not explicitly tied to any one in particular. It draws from a broad range of inspirations, including death rituals from the Anglican Church, “The Tibetan Book of the Dead,” Neoshamanism’s death rite known as the “great death spiral” and New Orleans jazz funerals, as well as text from the Bible and the traditional Catholic Mass.

Its five movements — Bryan associates that number with life — begin with a gentle, a cappella harmony built from elemental “mmm” sounds before each of the four voices of the Quince singers begins to follow a unique line, with detours into half-sung Sprechstimme and percussive sibilance. The other instruments don’t enter until about seven and a half minutes in, when the clarinet and brasses offer a chorale-like interlude, mournful and dignified.

The Requiem is primarily a showcase for the Quince singers. They follow that instrumental passage with repetitions of the word “listen,” in different ways: The score instructs one to exclaim, and the others to plead, chant on pitch and whisper. A bass drum resounds, signaling the start of a dirge that includes a duet of simultaneous yet lonely melodies from the clarinet and trombone. By the end, after sadly beautiful word painting with the “Kyrie eleison” text and a clarinet solo of upward runs, Bryan arrives at a finale that is less restful and resolved than a traditional Requiem’s, but more cyclical, closing with the “mmm” vocalise that started the piece.

Bryan talked more about the work and its inspirations in the interview. Here are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Was this commission specifically for a Requiem, or was that your choice?

It actually goes back to when I met Quince. I was really taken not only with their music and their voices, but also how they talked about music and the things that they cared about. We bonded, and then a year after that — about four years ago — we were talking, and I told them I would like to write an a cappella Requiem.

I grew up in an Anglican church and was deciding between the Catholic Mass and the Anglican Mass, and thinking of writing a Requiem, but in my own style. As I got into it, I started reading about different dying rituals from traditions around the world, how people approach funerals and the celebration of life. Then I took a pause, because it got really big. There was a lot to learn, and it was changing the way I approached it — and because we didn’t have a specific deadline, I stepped down.

Later, I heard from Missy Mazzoli about a commission at the Chicago Symphony, and I knew that Quince was on the program. So I changed it. The first section is still a cappella, but then I added instruments.

Even with more musicians, it’s still far from the scale of something like Verdi’s Requiem.

It was already going to be chamber size. But yeah, I ended up going kind of minimal with the way I used the instruments. I checked out classic Requiems, definitely Verdi’s and Mozart’s, and the feeling I got — or even just from reading the Catholic Mass — was this feeling of rising up against death. It feels like there’s a battle or a triumph, and I found that I was most interested in thinking about death and the cyclical nature of life and death, and more, kind of, an acceptance. So all my text was Christian, but it’s my perspective on the Requiem.

I was about to say, there’s a tension at the end of your piece, between triumphant language like “Death will be no more” and music that’s more unsettled and mysterious.

It felt like a natural ending because it’s a life cycle; it wasn’t a triumph or an arrival point. And with the text, “The first things have passed away,” I thought it was something that was not an ending or a beginning.

When you were exploring traditions of mourning, what did you find yourself attracted to, conceptually and artistically?

The one that hit home the most is just thinking about New Orleans — the idea of the celebration of life and the jazz funeral. There’s the walking of the casket from the church to the burial ground, but there’s a whole ceremony in a jazz funeral that starts with the dirge, and then it goes up-tempo to a celebration of life. So that was a major influence on the instruments that I chose: the brass band or the New Orleans ensemble. I wasn’t trying to replicate the style, necessarily, but there are little symbolic things.

What do you make of the context of this Requiem’s premiere, as opposed to spring last year?

I know some commissions come in response to this historic thing, and you have your own take, but this was something that I just wanted to do. That’s why it’s interesting that it took its own time and that the actual premiere is after this really profound time of loss. I find these kinds of things mysterious, how they happen. So, I hear it differently. It sort of came out of some of the work I was already doing, where I was writing music about police brutality. I wouldn’t say this piece is about that; it was a chance for me to go in deeper into these ideas about life and death.

Quince asked, in the middle of the rougher parts of the pandemic, how I would feel if they just recorded the first, a cappella part and put it online for people — just something to share. The folks at the Chicago Symphony were very supportive of that, so we did. It felt good to have something like that to offer, and I feel the same way as it is being offered now. I hope it will be healing to people.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

This is what ‘tree burials’ are like in Japan due to lack of space in cemeteries

by Explica .co

The families place the ashes on the ground, and plant an endemic species, forming forests in memory of the deceased.

Funeral rituals have accompanied human beings since they have notion of self. The earliest recorded burial is in Kenya, dating back 78,000 years. It is one of the oldest indications we have of a transcendence-oriented thinking: to the possibility that there is something beyond our earthly understanding.

With the advance of urbanization, and the apparently irreversible trend of population growth on the planet, the spaces to deposit the organic remains of the people has been compromised. We no longer fit. Given the situation, burials in Japan have had to take a new direction, which affects less the environment and appeals to a contemplative sense of eternal rest.

Rest in the shade of a tree

Natasha Mikles has dedicated her life to exploring the alternatives that exist to face death in the world. With the climate emergency in tow, the expert in philosophy from the University of Texas considers that the appropriation of physical land in favor of funeral practices it is simply no longer an option.

In recent years, Mikles has focused his study on Buddhist funeral rituals and narratives about the afterlife. In these Asian traditions, death is not understood as an end point. Rather, it is one more phase of the wheel of karma, and a step forward in the path to enlightenment.

Many times, however, the author acknowledges that “environmental needs collide with religious beliefs“, As detailed in his most recent publication for The Conversation. Rest perpetually under the shade of a tree in a public green area it could be an option, as is being seen in burials in Japan today.

A new way to face death

It is not the first time that burials in Japan have been practiced in this way. Since the 1970s, there has been a record of Japanese public officials fearing for the lack of funeral space for the population, particularly in urban areas. The problem deepened in the 1990s, when more serious alternatives began to be implemented throughout the island.

It was then that Jumokusō was thought of, which translates into Spanish as “tree burials.” In these, the families place the ashes on the ground, and plant an endemic species on site to mark its final resting space. In this way, instead of building more cemeteries, entire forests would be planted in memory of the deceased.

This principle leans from the Shinto tradition, which finds value in all the vital manifestations of the universe. For this reason, the spaces dedicated to this type of funeral rites are considered sacred: there is an intrinsic spiritual value in life that ends to make way for a new.

We suggest: Natural organic reduction: this is what ecological burials are like that turn your body into human compost

Do burials in Japan of this type interfere with traditional practices?

Many of the families that have implemented this strategy of sacred greening of public spaces they don’t even practice Shintoism, or are affiliated with a specific religious tradition. However, the interest in continuing this type of practice denotes a environmental responsibility extended throughout the population.

Despite this, these burials in Japan also obey an ancient Buddhist principle. Like the plants are considered sentient beings, it is a way to continue the reincarnation cycle for the soul that departed. Seeds embody a living component of this path, and therefore, they must protect themselves with the same honor.

The practice has been so well received that various temples and public cemeteries have adopted it as part of their agenda today. The model has been so successful that some Religious spaces promote it as part of the spiritual life of people. Although they do not necessarily align with the ancient practices originally proposed by Buddhism, they do obey the precept of respect for existing forms of life, which sets the standard for all branches of this spiritual tradition.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Dr. Ruth talked about sex in the 1980s. Now it’s time to talk about death

‘The pandemic has waved death in our face. Mortality is now at the forefront’

Only Karen Hendrickson and Jo-Anne Haun, co-founders of Death Doula Network of BC (DDNBC), can approach the topic of death with the perfect balance of positivity, passion, and of course, dark humour.

“Back in the 1980s, Dr. Ruth talked about sex,” Haun said in a Zoom interview from B.C. “She brought education and humour to it and now our children are learning about it in schools. That’s what we would like to do with death.”

Commonly associated with births, doulas offer physical and emotional support. They often handle administration and act as a go-between for patients and medical staff to minimize stress for patients and their families.

But doulas also play a role in end of life. “Death doulas” not only fill the gaps between patients and the health-care system, but also bridge the gap between the health-care and funeral industry. Their work has become particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has isolated dying patients, interrupted death rituals and placed extra stress on families.

Hendrickson and Haun, who have been friends for 20 years, became death doulas together back in 2018. They founded the virtual group to start a discussion around death and dying for anyone interested in the death-positive movement.

DDNBC has grown quickly and continuously since their first virtual meeting in April 2020. The network now has close to 140 members throughout Canada and around the world.

Gaps in the health-care system

Hendrickson and Haun have been part of the fight to include doulas within the health-care system to help fill some of the gaps between the system as its patients.

“You have likely heard of the rock metaphor before. Basically, The big rocks are the diagnoses. The medium rocks are your support people. The small rocks are your treatments. The sand in between the rocks is the doula,” Hendrickson said.

Things like confusing paperwork, new medical teams, and unfamiliar systems have a devastating emotional impact on patients and their families.

Hendrickson described an instance where a young patient with terminal cancer kept having to renew his burial permit but the medical staff continued to insist that it wasn’t important. That form is required by funeral services to take the person’s body from their home. Without an up-to-date form, the funeral service would refuse to take the body and the family would have to call the police.

“They would arrive with their sirens on and everything, and be forced to treat it like a crime scene because that’s their mandate,” Hendrickson said. “Imagine grieving families having to witness that.”

Ingrid Ollquist, based in Los Angeles, started as a birth doula in 2017, mainly supporting people through abortions and miscarriages. She decided to become a pre-planning and post-death doula after receiving emotional support from a doula mentorship program herself.

After a 10-year battle, Ollquist lost her mother to multiple sclerosis (MS). During this process, she was in and out of hospitals dealing with lots of administration with little support. As a death doula, she hopes to prevent others from experiencing this stress and isolation.

“It brought distance between my mom and I,” Ollquist said. “It was so frustrating to just live in logistical spaces with a person that you love that you can see dying in front of you.”

Ollquist is now the founder of the free grief support group Nurture Ing after being mentored by Jill Schock, the founder of Death Doula LA (DDLA).

COVID-19 has changed how we die

COVID-19 has made the gaps between health-care and funeral industries larger. Government regulations restrict patients from having more than one support person when in a hospital.

For death doulas, these restrictions mean patients die without their loved ones by their side. Doulas and family members must connect with the dying patient virtually.

“A COVID death is horrific. It’s the worst. You are losing more than just life, but all end-of-life rituals,” Ollquist said.

Many memorial and funeral events have been cancelled, and burial and cremation services have been substantially delayed.

Olliquist hasn’t personally dealt with more clients but she has played a larger role in supporting other doulas. She says that many doulas are now experiencing death anxiety after witnessing numerous horrific deaths all over the world. People of all different ages are dying without family and without rituals.

DDNBC and Ollquist suspect that more people are going to be thinking about (and planning for) their deaths after the pandemic.

“The pandemic has waved death in our face. Mortality is now at the forefront,” Haun said.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What to Expect When Death Comes

In the wake of Covid-19, we are all grieving. How can we come to terms with death — and what does it teach us about living?

In 2015, I published a book. It began like this:

“A wake,” my mother said. “To sit with the dead.”

We were on our way to West Virginia, to an unremarkable two-story colonial where my grandfather’s remains had been washed and laid out for viewing. It had been raining all night, but apparently no one in this homey funeral parlor had been sleeping. They’d been sitting up with the body. Sitting up — with the body — all night.

There are no good adjectives to describe my feelings about this. I was seventeen and grieving, but I wasn’t horrified. Shocked, yes, but the idea was strangely enticing, even fascinating. Really? We do that? This wasn’t my first family death, after all, but it was the first time I’d encountered the intimacy of this ritual.

It was also the first time I’d considered the buzzing activity that surrounds the newly dead. I asked myself what seemed like suddenly obvious questions — Why wash a body before putting it in the dirt? Why sit awake with someone now permanently asleep? Even the practice of embalming the body (which prevents decay) before interring it in the ground (where it is supposed to decay) struck me as a very strange kind of ritual. With only a minor leap of morbid imagination, care of the newly dead began to resemble care of the newly born. But it also brings us face to face with our own mortality.

When we witness death, we must grapple with its finality, but also with the knowledge that one day we, too, must die. Where once this was understood as the natural order of things, we now find ourselves conflicted and less willing to see death as “natural.” If anything, death breaks into our lives as an unexpected surprise.

We are not used to death and dying in the West, and most particularly not in the modern United States. The Victorians (in the U.S. and U.K.) had incredibly complex mourning rituals, including mourning jewelry, photographs of the recently dead (momento mori photography), and the public wearing of mourning clothing.

Like birth, death was a social event that drew communities together. In a large city, scarcely a day would go by without some visible sign of bereavement. Compare this with our modern standards, where illness and death are either hidden away in hospitals or sensationalized through popular culture, and where prolonged grief is likely to be medicated as abnormal, rather than openly acknowledged as an inevitable part of life.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a Swiss American psychiatrist, developed her theory of the five stages of grief in 1969 as a response to a lack of information on death and dying in the curriculum of medical schools — but even these hardly cover the enormous range of emotions that accompany death, and they certainly weren’t a plan for how better to go about the process of grieving. Later attempts at death positive education have been on the rise, but can be blind to the way privilege often determines “positivity” about death.

Then, in 2020, the pandemic descended upon us with death tolls on a global scale. We crashed into a set of experiences most were ill-prepared to deal with — and on top of this, the nature of the virus stole away even our usual means of communal grieving. Covid-19 has precipitated three separate types of loss; first, the loss of loved ones, of friends, of connections we always assumed would be there. Second, the loss of personal contact so much a part of grieving. And third, and perhaps most jarring: the loss of an illusion. We’ve been stripped of the comfortable idea that we could plan for tomorrow, or that we will all die of comfortable old age.

Death has come. And we were not expecting it.

Looking out at the expanse of still-spiking cases in the U.K. and parts of the U.S., overwhelmed crematoriums in India, and the struggle to get higher percentages vaccinated, it’s clear that the first crisis isn’t necessarily over. But a second epidemic is coming: a shadow epidemic of psychological grief as we try to fit puzzle pieces of broken yesterdays to almost-tomorrows. We need help. So: what next?

I think it’s time for a journey. In Death’s Summer Coat, I worked backward through history, and sideways into other cultural contexts, to see how we got to “now.” Along the way, I learned how we might find paths to something better. I’ve decided to revisit those paths from a post-outbreak perspective, in hopes it might shed light on the road ahead. I hope you will join me. Sharing our stories provides hope and community so that none of us face death alone in the silent dark.

If you would like to hear a bit more from me, I gave a brief chat on the topic for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland. Until next time, go gently with yourselves.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

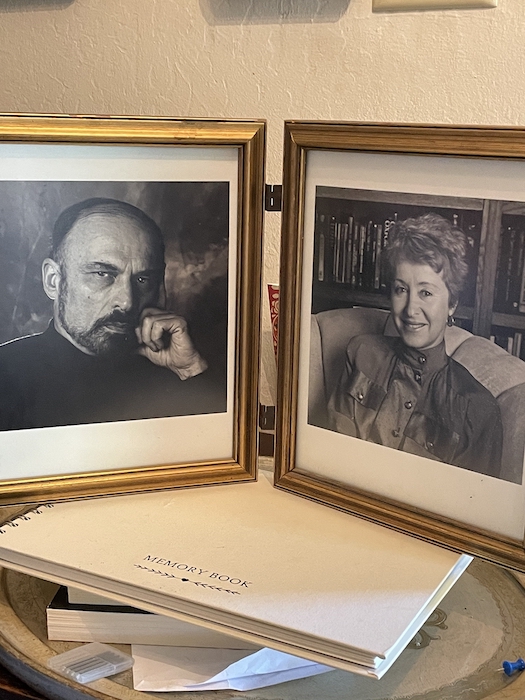

What matters in the end?

Couple chronicles life’s final chapter in new book

Authors Irvin and Marilyn Yalom probe questions around love, loss

Is it possible to plan a “good death?” Can one gracefully leave this world to the next generation? Can one live meaningfully until the very end?

Prompted by a serious medical diagnosis, longtime Palo Alto residents Irvin and Marilyn Yalom probe these questions in “A Matter of Death and Life,” which the duo wrote just before Marilyn died by medically assisted suicide in 2019.

Married 65 years, both Yaloms already were widely published authors — translated into many languages — when they began writing their book in spring 2019 after Marilyn was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells.

Irvin, a psychiatrist and leader in the field of existential psychotherapy, had some 20 fiction and nonfiction titles to his name. Marilyn, a cultural historian, French professor and early director of Stanford’s Center for Research on Women, had published at least 10 books.

With her prognosis bleak, Marilyn persuaded her husband that they should document, in alternating chapters, the experience of her illness and likely demise from the disease.

“We now live each day with the knowledge that our time together is limited and exceedingly precious,” the two, both in their late 80s, write in the preface. “This book is meant, first and foremost, to help us navigate the end of life.”

As scholars, both Yaloms are steeped in the great philosophers’ contemplations on exemplary life and death, and have wrestled in their own work with themes of mortality.

In “American Resting Place,” co-authored with their son, the photographer Reid Yalom, Marilyn documented how 400 years of gravestones, graveyards and burial practices reflect changing American ideas about death, class, gender and immigration.

As a psychotherapist, Irv had counseled countless patients, including many with terminal illnesses, about facing death, and written extensively about their — and his own — death anxieties.

“Of all the ideas I’ve employed to comfort patients dreading death, none has been more powerful than the idea of living a regret-free life,” Irv recalls in the book.

Sitting together in their yard, admiring the trees, “Marilyn squeezes my hand and says, ‘Irv, there’s nothing I would change,'” he writes. With four children, eight grandchildren and extensive world travels in addition to their professional accomplishments, both Yaloms feel they’ve seized their days to the fullest.

Even as death approaches, the pair celebrate “magic moments,” such as the evening they abandon television and Marilyn pulls “Martin Chuzzlewit” down from the bookshelf and begins reading aloud. “I purr in ecstasy, listening to each word,” Irv writes. “This is sheer heaven: What a blessing to have a wife who delights in reading Dickens’s prose out loud.” He recalls the day — more than 70 years before — when the two had first bonded over their mutual love of books as classmates at Roosevelt High School in Washington, D.C.

When chemotherapy fails and Marilyn is placed on immunoglobulin therapy, she begins inquiring about medically assisted suicide — legal in California since 2016 — in the event the new treatment does not work.

Irv is horrified, but Marilyn is at peace. Though sad to leave the people she loves, “The idea of death does not frighten me,” she writes. “I can accept the idea that I shall no longer exist. … After 10 months of feeling awful most of the time, it’s a relief to know that my misery will come to an end.”

After some weeks the couple is told the immunoglobulin therapy, too, has failed.

Marilyn accepts various tributes and goes about saying her goodbye, and giving away her treasured books to a large network of friends and colleagues. “It’s weird to realize that if I want to do anything, I’ll have to do it quickly,” she writes.

Ultimately, about a week before Thanksgiving 2019, she chooses to end her life, ingesting lethal medication in the presence of Irv, their four children, a physician and a nurse. (She was among the 405 people to use California’s End of Life Options Act in 2019, according to the annual tally from the state health department.)

Shortly before, Marilyn had reviewed the writings of Greek and Roman philosophers on how to live and die well. “For all the philosophical treatises and all the assurances of the medical profession,” she writes, “there is no cure for the simple fact that we must leave each other.”

The final chapters are written by Irv, recounting the agony of grief and his halting attempts to resume some kind of normal life — including venturing out to a Barron Park Senior Lunch at the Corner Bakery.

After more than 70 years with Marilyn beside him, he struggles with the idea that “something can have value, interest and importance even if I am the only one to experience it, even if there’s no Marilyn to share it with.

“It’s as if Marilyn’s knowing about a happening is necessary to make it truly real,” he writes.

He rails at the irrationality of this. “I’ve been a full-time student, observer and healer of the mind for over 60 years, and it is difficult to tolerate my own mind being so irrational,” he writes.

Reached at his home in late May, two months after the book’s publication, Yalom said he’s been busy with the “strong feedback,” including virtual book talks with large audiences all over the world. The book is licensed for publication in 25 countries, some already in print and others likely between now and the end of next year, according to literary agent Sandra Dijkstra.

Yalom, who turns 90 this month, continues to work on his next book and also to do single-hour therapy consultations.

“I’m growing old now and my memory’s beginning to disappear,” he said. “I’m not seeing ongoing patients anymore but I think I’m able to do a lot for some people just in the single hour.”

His new book is intended as a training manual for young therapists. “I’m always writing, and as long as I’m writing I feel very well,” he said.

He also takes walks daily to a nearby park, where he’s had a bench installed in memory of Marilyn. Yalom said he enjoys sitting on the bench, taking in the surroundings and thinking of her.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Coping with death through letters to the dead

By Mathew Brock

Some people may regret not being able to say something to a loved one before they passed, but for the next month, residents and visitors to Lincoln City will have the chance to put those words into one final letter, even if it’s only symbolically.

At parks around Lincoln City, several altars appeared last month as part of the Last Word’s Mailbox Altars Public Art Installation, which gives people who have experienced the death of a loved one a place to grieve and cope by writing them letters.

The project serves another purpose however, as the letters left at the alters will be taken and turned into songs that will be performed at a virtual concert in August and sold as an album to help raise money in support of houseless veterans facing terminal illness through the Do Good Multnomah nonprofit group.

“These art installations are part of an interdisciplinary project that’s really a fundraiser,” said Crystal Akins, founder of Activate Arts and the artist responsible for the project. “I knew I could have done a regular fundraiser, like an event where you get wine and do the whole thing, but instead I wanted to do something that would bring the community together around death using their own grief and loss to transform that into a way to support a person in dying a good death.”

The project has been years in the making and was inspired by Akins’ work as a death doula, someone who helps the dying and their friends and family cope with death.

“It’s a long-term project, and I’ve been working on it for about five years so far,” Akins said. “I’ve been researching houseless death and am a death doula. I’ve been working with a lot of people who live in poverty and seeing how they die. I decided now it’s time to help build a community around death and to help veterans in poverty get access to a good death.”

Akins said the project was also inspired by the Telephone in the Wind art project, which first started in Japan with similar installations popping up in the U.S. and other countries since it debuted in 2011. At these installations, visitors can use a secluded phone booth to symbolically have one final conversation with a deceased loved one as a way to help cope with the loss.

“I saw that and the ways people were connecting with it and wanted to bring something similar here to try that would help bring community together,” Akins said. “Some of the letters I’ve been getting so far have taken the time to thank me for providing this space, and that was the purpose of this, to provide a space for people to experience grief and loss, which is especially important during this pandemic with people facing loss every day.”

The alters themselves were made by Akins using a “found art” art style, which takes discarded and recycled items and repurposes them as a medium for artwork. They’re currently located at Josephine Young Memorial Park, Siletz Bay Park and Nesika Park in Lincoln City until July 1, when Akins will collect and store them.

Those wishing to participate in the project can visit any of the altars and leave a letter, and if they like, a small offering as well, such as a flower, photo or rock. Those writing letters are asked to keep their own privacy in mind and to address letters without specific names, such as “Dear Dad,” “Dear Grandmother,” “Dear sister,” or “Dear Pet Companion.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

You can’t choose an afterlife.

But you can choose what happens to your body after your life.

There are many options for what happens to your body after your death. But there’s only one real way to give it a long afterlife.

By Adam Larson

Gardeners can be very picky about the kind of compost they use, but this year Washington-based business Recompose has begun making it from a new ingredient: human remains. Intended as an eco-friendly funeral alternative, interested parties should perhaps be forewarned: It takes a couple of months to go from corpse to compost.

But (legally) composting yourself or a recently departed loved one is by no means the only unusual alternative to traditional burial or cremation.

You — or someone’s remains for which you are legally responsible — can now be buried in a suit made of cotton and mushroom spores, intended to make a person’s body into fungus food. (The process also claims to clean heavy metals from the deceased’s remains before they seep into the soil.)

If one is a fan of the ocean, there are companies that will take cremated remains and incorporate them into artificial reefs to act as a home for coral and fish.

The deeper question you might want to ask may be why we care what happens to our dead bodies at all.

If you’d prefer your earthly remains to stay closer to your loved ones (or they would prefer to keep your remains close), your post-cremation ashes can be made into a diamond and worn as jewelry or transformed into a glass paperweight for a bizarre cubicle talking piece.

Conversely, if you’d rather get away from Earth altogether, you could have your ashes shot into space, where they would then orbit the Earth before disintegrating upon future re-entry. If you’d like to really get away, your ashes could be shot out of orbit and into deep space. That is what was done with the remains of Clyde Tombaugh, who discovered Pluto; his remains came within 8,000 miles of the dwarf planet and are currently over 4 billion miles from Earth.

After hearing the many options of what to do with your body after you’re done using it, you might have some questions. But the deeper question you might want to ask may be why we care what happens to our dead bodies at all.

Part of the issue is that many religions believe what happens to our remains is important. Hindus cremate their dead because they believe their souls will only leave their bodies if forced to leave. Zoroastrians believe that dead bodies are impure and must be disposed of properly. Ancient Egyptians believed their bodies needed to be preserved because they were the vessels that contained their spirits.

If you actually want to make a difference after you’re gone, there are better choices.

But even people who don’t hold beliefs about the importance of the physical body in the afterlife still follow funeral customs. Around the world, most people (even those without a belief in an afterlife) would be weirded out by the prospect of the body of a loved one (or their own body) being unceremoniously tossed into a landfill, which is strange when you think about it. After all, it’s not as if dead people need their bodies for anything: They’re dead.

Clearly, another part of the human adherence to funeral rituals across time and cultures has to do with a desire to be remembered after we are gone and the idea that we now express as some version of “funerals are for the living.” A gravesite can help keep the memory of the deceased alive for their remaining loved ones, give mourners a specific place to commemorate the dead and make them feel closer to the deceased. But if you really think about it absent our cultural norms, even this is a bit odd, because you aren’t actually closer to the person who died at a gravesite.

You’re just closer to their corpse or ashes, and regardless of your personal belief system, you probably actually consider the intangibles of a person — whether you want to call that their heart or their soul or their mind — the essence of what makes them who they are, rather than their physical body.

Yet while we know that, we still have difficulty separating the idea of the mind from the body. Perhaps that’s because we can’t communicate with other humans without interacting with a physical body to some degree. Disrespecting a person’s remains, no matter how little they “are” the person anymore, still feels like disrespecting the person.

Part of the human adherence to funeral rituals across time and cultures has to do with a desire to be remembered after we are gone

So why, then, do some people want their bodies to become compost, coral reefs or mushroom food? A major motivator seems to be concern for the environment. The embalming fluid used to keep remains presentable for typical American funerals is good at preserving dead things but can also make other things die (if, for instance, it’s ingested by underground organisms — though U.S. regulations mandate that caskets be sealed to avoid things inside from leaking outside).

And while cemeteries only cover a tiny fraction of the Earth’s surface, they are often located in cities, where land can be in short supply, and severe water events like floods can cause serious issues for the living, who generally prefer that caskets (and the bodies inside them) stay buried.

Plus, traditional funerals and burials can be prohibitively expensive. Add to that a general decline in people practicing organized religion, and it means that more people in the United States are not restricted by the rules and regulations of faith traditions that might prohibit certain post-death practices.

Cremation, then, is often seen as a more eco-friendly (and much less expensive) alternative to burial, but burning the deceased’s remains releases greenhouse gases and mercury into the atmosphere — although a relatively new form of cremation produces fewer emissions and uses less energy.

After hearing the many options of what to do with your body after you’re done using it, you might have some questions.

So becoming compost — or something similar — seemingly lets your body do some good after you’re gone. The opportunity to help others is the ethos behind the similar, but much older, practice of Tibetan sky burials (though, in a sky burial your body provides sustenance for vultures instead of hydrangeas).

But if you actually want to make a difference after you’re gone, there are better choices than turning your body into compost or vulture food. You can make compost out of human remains or the leftovers you forgot at the back of the refrigerator, but only one of those can save lives when used in a different way.

First and foremost, you can register as an organ donor. You won’t need your kidneys after you shuffle off this mortal coil, but there are more than 80,000 Americans who could use them right now and a single organ donor could potentially save eight lives.

While organ donation generally still leaves people with the option for burial, cremation or composting, there’s another option: donating your remains entirely to science. Donated bodies are used to train the next generation of doctors in medical schools, provide insight into human variation and even reveal how our bodies naturally decay — to help forensic anthropologists identify murder victims and catch their killers. Like organ donation, donating a body to science can save lives.

You might not get the chance to save the lives of others while you’re alive. But you do have the chance to make a simple decision while you’re still with us that can help others live longer after you’re gone.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!