By JESSICA NUTIK ZITTER, M.D.

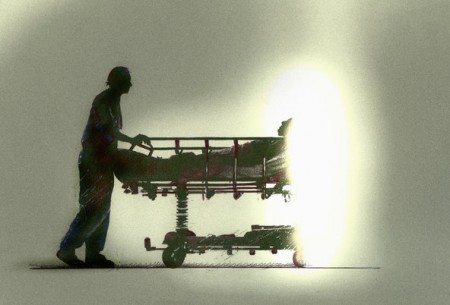

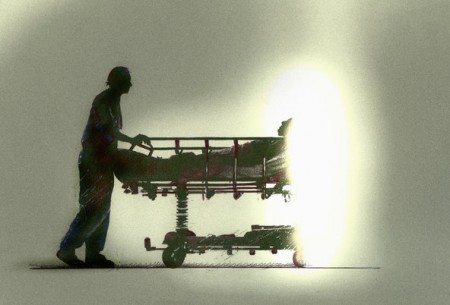

Sadly, but with conviction, I recently removed breathing tubes from three patients in intensive care.

As an I.C.U. doctor, I am trained to save lives. Yet the reality is that some of my patients are beyond saving. And while I can use the tricks of my trade to keep their bodies going, many will never return to a quality of life that they, or anyone else, would be willing to accept.

I was trained to use highly sophisticated tools to rescue those even beyond the brink of death. But I was never trained how to unhook these tools. I never learned how to help my patients die. I committed the protocols of lifesaving to memory and get recertified every two years to handle a Code Blue, which alerts us to the need for immediate resuscitation. Yet a Code Blue is rarely successful. Very few patients ever leave the hospital afterward. Those that do rarely wake up again.

I was trained to use highly sophisticated tools to rescue those even beyond the brink of death. But I was never trained how to unhook these tools. I never learned how to help my patients die. I committed the protocols of lifesaving to memory and get recertified every two years to handle a Code Blue, which alerts us to the need for immediate resuscitation. Yet a Code Blue is rarely successful. Very few patients ever leave the hospital afterward. Those that do rarely wake up again.

It has become clear to me in my years on this job that we need a Code Death.

Until the early 20th century, death was as natural a part of life as birth. It was expected, accepted and filled with ritual. No surprises, no denial, no panic. When its time came, the steps unfolded in a familiar pattern, everyone playing his part. The patients were kept clean and as comfortable as possible until they drew their last breath.

But in this age of technological wizardry, doctors have been taught that they must do everything possible to stave off death. We refuse to wait passively for a last breath, and instead pump air into dying bodies in our own ritual of life-prolongation. Like a midwife slapping life into a newborn baby, doctors now try to punch death out of a dying patient. There is neither acknowledgement of nor preparation for this vital existential moment, which arrives, often unexpected, always unaccepted, in a flurry of panicked activity and distress.

We physicians need to relearn the ancient art of dying. When planned for, death can be a peaceful, even transcendent experience. Just as a midwife devises a birth plan with her patient, one that prepares for the best and accommodates the worst, so we doctors must learn at least something about midwifing death.

For the modern doctor immersed in a culture of default lifesaving, there are two key elements to this skill. The first is acknowledgment that it is time to shift the course of care. The second is primarily technical.

For my three patients on breathing machines, I told their families the sad truth: their loved one had begun to die. There was the usual disbelief. “Can’t you do a surgery to fix it?” they asked. “Haven’t you seen a case like this where there was a miracle?”

I explained that at this point, the brains of their loved ones were so damaged that they would most likely never talk again, never eat again, never again hug or even recognize their families. I described how, if we continued breathing for them, they would almost definitely be dependent on others to wash, bathe and feed them, how their bodies would develop infection after infection, succumbing eventually while still on life support.

I have yet to meet a family that would choose this existence for their loved one. And so, in each case, the decision was made to take out the tubes.

Now comes the technical part. For each of the three dying patients, I prepped my team for a Code Death. I assigned the resident to manage the airway, and the intern to administer whatever medications might be needed to treat shortness of breath. The medical student collected chairs and Kleenex for the family.

I assigned myself the families. Like a Lamaze coach, I explained what death would look like, preparing them for any possible twist or turn of physiology, any potential movements or sounds from the patient, so that there would be no surprises.

Families were asked to wait outside the room while we prepared to remove the breathing tubes. The nurses cleaned the patients’ faces with warm, wet cloths, removing the I.C.U. soot of the previous days. The patients’ hair was smoothed back, their gowns tucked beneath the sheets, and catheters stowed neatly out of sight.

Then, the respiratory therapist cut the ties that secured the breathing tube around the patients’ neck. As soon as the tubes were removed and airways suctioned, families were invited back into the room. The chairs had been pulled up next to the bed for them and we fell back into an inconspicuous outer circle to provide whatever medical support might be needed.

I stood in the back of the room, using hand motions and quietly mouthing one-word instructions to my team as the scene unfolded — another shot of morphine when breathing worsened, a quick insertion of the suction catheter to clear secretions. We worked like the well-oiled machine of any Code Blue team.

Of those three Code Death patients, one died in the I.C.U. within an hour of the breathing tube’s removal. Another lived for several more days in the hospital, symptoms under watch and carefully managed. The third went home on hospice care and died there peacefully the next week, surrounded by family and friends.

I would argue that a well-run Code Death is no less important than a Code Blue. It should become a protocol, aggressive and efficient. We need to teach it, practice it, and certify doctors every two years for it. Because helping patients die takes as much technique and expertise as saving lives.

Complete Article HERE!