“I asked my audience to keep that in mind that it’s this social dimension of the dying process that gives us the best context for understanding this delicate issue. I suggested that if we kept our discussion as open-ended as possible we wouldn’t be tempted to reduce the whole affair to the single issue of assisted suicide, because that does nothing but polarize the debate.”

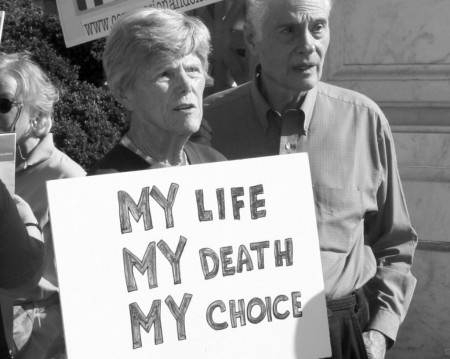

There was a wonderful front-page article in the February 2, 2014 edition of the New York Times titled: ‘Aid in Dying’ Movement Takes Hold in Some States. The most astonishing about the article was that, not too long ago, this sort of even-handed presentation in “the paper of record” would have been unthinkable. I’m so glad this is changing. Because, despite where you stand on the issue, no one benefits from tamping down the discussion.

I talk about assisted dying frequently. Despite being the hot button issue it is, there’s a remarkable amount of common ground amongst the varying positions if one looks for it.

I was conducting a workshop on this very topic recently and before I could really get started, a man stood up and declared: “I need to say upfront that I am diametrically opposed to assisted suicide of any kind, including physician assistance. There’s just too much room for abuse. I can’t help but think about how things would be if we started eliminating the people we think are no longer productive. You could be sure that old and disabled people would be the first to get the ax. I’m afraid the tide of this culture’s prejudice against age and infirmity would overwhelm them. It is such a slippery slope that I don’t think we ought to venture out onto it.”

Not five minutes into the workshop and I already knew it was gonna be a bumpy ride. I asked the fellow for his indulgence and asked him to allow me to continue.

I began by saying: “It’s my experience that very few people prefer to die alone. Most dying people express a desire to have company in their dying days. And given the option, most everyone would prefer the company of friends and family to that of strangers. Very few of us have the personal strength to walk this unfamiliar territory alone. We’re social beings, after all, and there’s nothing about dying that changes that.”

I began by saying: “It’s my experience that very few people prefer to die alone. Most dying people express a desire to have company in their dying days. And given the option, most everyone would prefer the company of friends and family to that of strangers. Very few of us have the personal strength to walk this unfamiliar territory alone. We’re social beings, after all, and there’s nothing about dying that changes that.”

I asked my audience to keep in mind that it’s this social dimension of the dying process that gives us the best context for understanding this delicate issue. I suggested that if we kept our discussion as open-ended as possible we wouldn’t be tempted to reduce the whole affair to the single issue of assisted suicide, because that does nothing but polarize the debate.

I turned to address the man who stood up at the beginning of the workshop. “I thought it curious, sir, that you took the time to assert that you are opposed to assisted suicide of any kind, including physician assisted suicide. Is that all you thought we were going talk about?”

“Well, yes, that’s exactly what I thought. Isn’t that what assisted dying means?”

“Not the way I understand it.” I said. “It’s true, acting to hasten death in the final stages of a terminal illness falls under the general heading of assisted dying, but I don’t think it defines the concept. In fact, I believe that reducing the concept of assisted dying to a single issue would be a mistake for two reasons. First and foremost, it discounts all the other more common modes of assistance regularly being given to dying people across the board. And second, this more extraordinary form of assistance is relatively uncommon. So you can see why I’m so adamant about keeping the discussion inclusive and open ended. It just wouldn’t be balanced otherwise. I believe that the issue of proactive dying can become sensationalized, distorted, and even freakish if this option is not presented as an integral part of the entire spectrum of end of life care.”

I think a good metaphor for what I was talking about is the midwife. Like a birth midwife, a death midwife assists and attends in a myriad of ways. A midwife is the one who is most present and available to the dying person, the one who listens, comforts, and consoles. But a midwife may also bring an array of other basic skills, like expertise in the care of the body such as bathing, waste control, adjusting the person’s position in bed, changing bedclothes, mopping the person’s brow, or keeping the person’s eyes and mouth lubricated. A midwife may also be proficient in holistic pain management and comfort care such as massage, breath work, visualization, aromatherapy, relaxation, and meditation.

A midwife may take responsibility for maintaining a tranquil and pleasing dying environment. Often this means arranging the person’s home or room, not only in terms of the practical considerations, but also in terms of the aesthetic as well. This may include arranging flowers and art, reading aloud or playing music softly. A death midwife, like a birth midwife takes the lead role in the caring for and comforting the one who is dying. Without this kind of compassionate presence, few people would have the opportunity to achieve a good death.

Another guy spoke up: “That’s all fine and good, but I was hoping that we were going to talk about, you know, the more proactive aspects of assisted dying. I mean, I know I’m gonna want help in bringing my life to a close when the time comes and no amount of breathing exercises and adjusting pillows is gonna cut it. Am I making myself clear?”

“I understand what you are saying. You want some practical advice on how to end your life if the need arises.” I responded. “I can assure you that we well get to that. I just wanted to make sure that we all appreciate the context of our discussion.”

An elder woman in the first row raised her hand. “I’m glad that you’re taking the time to help us frame the debate in this way because I’m confused. I have the same reservations as the first gentleman who spoke, but now I’m not sure my concerns are warranted. Maybe I need more time to figure out what it is we’re talking about when you say, ‘proactive dying.’ Is it euthanasia, assisted suicide, self-deliverance, what? And why so many different terms?”

An elder woman in the first row raised her hand. “I’m glad that you’re taking the time to help us frame the debate in this way because I’m confused. I have the same reservations as the first gentleman who spoke, but now I’m not sure my concerns are warranted. Maybe I need more time to figure out what it is we’re talking about when you say, ‘proactive dying.’ Is it euthanasia, assisted suicide, self-deliverance, what? And why so many different terms?”

“You make a very good point, ma’am. Unfortunately, there is no agreement, even among experts, about a common vocabulary for this debate. And thus the public discourse often generates a whole lot more heat than light. And the topic of proactive dying will continue to be a hot-button issue until we can come to a consensus about the parameters of the debate, and that seems like a long way off.”

I went on to say that I have trouble with most all the terms commonly used in the debate. I consider euthanasia is much too technical. Curious enough, at one time this word meant an easy, good death. Now, unfortunately, it is defined as mercy killing, a classic example of how language can be corrupted.

I also try to avoid using the term “assisted suicide” when I talk about someone hastening his or her death in the final stages of a terminal illness. The word suicide is inappropriate in this instance, because suicide usually denotes a desperate cry for help, which is rarely if ever the case for those facing the imminent end of life.

Finally, I don’t much like the term self-deliverance either. It’s just one of those vague, contemporary euphemisms that does nothing to clear the air. In fact, when polled, most people haven’t a clue what self-deliverance means. I prefer the simpler, more straightforward terms ‘proactive dying’ or ‘aid in dying.’

Another woman spoke up: “I’m having a hard time with this too. I mean, it’s all so confusing and there are so many subtleties to consider. I guess I’d have to say that I’m not particularly comfortable with the notion of assisted suicide or, as you call it, aid in dying. But I wonder if I’d feel differently if I were in unbearable pain. And taking someone off life support; isn’t that technically assisted dying? Where do we draw the line between what is acceptable and what isn’t? And who is going to make that determination?”

I responded: “The simple answer is that doctors and lawyers are generally the ones who make the call. That is unless individuals are granted the right to choose. But even then, medical and legal concerns can and do trump a person’s wishes.”

(We will take up this topic again next time. I’ll discuss how best to approach one’s physician about aid in dying among other things.)