Seattle aid-in-dying patient chooses his last day

A former world traveler, triathlete and cyclist McQ had been in pain and physical decline for years. Last fall, he decided to use Washington state’s 2009 Death With Dignity law to end his suffering.

In the end, it wasn’t easy for Aaron McQ to decide when to die.

The 50-year-old Seattle man — a former world traveler, triathlete and cyclist — learned he had leukemia five years ago, followed by an even grimmer diagnosis in 2016: a rare form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS.

An interior and urban designer who legally changed his given name, McQ had been in pain and physical decline for years. Then the disease threatened to shut down his ability to swallow and breathe.

“It’s like waking up every morning in quicksand,” McQ said. “It’s terrifying.”

Last fall, McQ decided to use Washington state’s 2009 Death With Dignity law to end his suffering. The practice, approved in seven states and the District of Columbia, allows people with a projected six months or less to live to obtain lethal drugs to end their lives.

Although the option was legal, actually carrying it out was difficult for McQ, who agreed to discuss his deliberations with Kaiser Health News. He said he hoped to shed light on an often secretive and misunderstood practice.

“How does anyone get their head around dying?” he said, sitting in a wheelchair in his apartment in late January.

More than 3,000 people in the U.S. have chosen such deaths since Oregon’s law was enacted in 1997, according to state reports. Even as similar statutes have expanded to more venues — including, this year, Hawaii — it has remained controversial.

California’s End of Life Option Act, which took effect in 2016, was suspended for three weeks this spring after a court challenge, leaving hundreds of dying patients briefly in limbo.

Supporters say the practice gives patients control over their own fate in the face of a terminal illness. Detractors — including religious groups, disability-rights advocates and some doctors — argue such laws could put pressure on vulnerable people and that proper palliative care can ease end-of-life suffering.

Thin and wan, with silver hair and piercing blue eyes, McQ still could have passed for the model he once was. But his legs shook involuntarily beneath his dark jeans and his voice was hoarse with pain during a three-hour effort to tell his story.

“How do you decide?”

Last November, doctors told McQ he had six months or less to live. The choice, he said, became not death over a healthy life, but a “certain outcome” now over a prolonged, painful — and “unknowable” — end.

“I’m not wanting to die,” he said. “I’m very much alive, yet I’m suffering. And I would rather have it not be a surprise.”

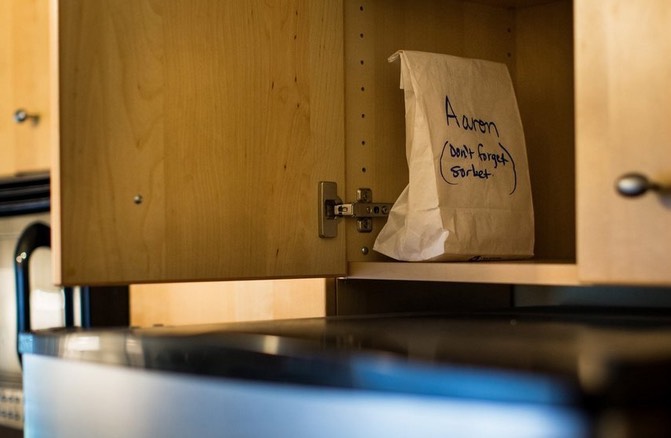

In late December, a friend picked up a prescription for 100 tablets of the powerful sedative secobarbital. For weeks, the bottle holding the lethal dose sat on a shelf in his kitchen.

“I was not relaxed or confident until I had it in my cupboard,” McQ said.

At the time, he intended to take the drug in late February. Or maybe mid-March. He had wanted to get past Christmas, so he didn’t ruin anyone’s holiday. Then his sister and her family came for a visit. Then there was a friend’s birthday and another friend’s wedding.

“No one is ever really ready to die,” McQ said. “There will always be a reason not to.”

Many people who opt for medical aid-in-dying are so sick that they take the drugs as soon as they can, impatiently enduring state-mandated waiting periods to obtain the prescriptions.

Data from Oregon show that the median time from first request to death is 48 days, or about seven weeks. But it has ranged from two weeks to more than 2.7 years, records show.

Neurodegenerative diseases like ALS are particularly difficult, said Dr. Lonny Shavelson, a Berkeley, Calif., physician who has supervised nearly 90 aid-in-dying deaths in that state and advised more than 600 patients since 2016.

“It’s a very complicated decision week to week,” he said. “How do you decide? When do you decide? We don’t let them make that decision alone.”

Philosophically, McQ had been a supporter of aid-in-dying for years. He was the final caregiver for his grandmother, Milly, who he said begged for death to end pain at the end of her life.

By late spring, McQ’s own struggle was worse, said Karen Robinson, McQ’s health- care proxy and friend of two decades. He was admitted to home hospice care, but continued to decline. When a nurse recommended that McQ transfer to a hospice facility to control his growing pain, he decided he’d rather die at home.

“There was part of him that was hoping there were some other alternative,” Robinson said.

McQ considered several dates — and then changed his mind, partly because of the pressure that such a choice imposed.

“I don’t want to talk about it because I don’t want to feel like, now you gotta,” he said.

Coconut water, vodka, friends

Along with the pain, the risk of losing the physical ability to administer the medication himself, a legal requirement, was growing.

“I talked with him about losing his window of opportunity,” said Gretchen DeRoche, a volunteer with the group End of Life Washington, who said she has supervised hundreds of aid-in-dying deaths.

Finally, McQ chose the day: April 10. Robinson came over early in the afternoon, as she had often done, to drink coffee and talk — but not about his impending death.

“There was a part of him that didn’t want it to be like this is the day,” she said.

DeRoche arrived exactly at 5:30 p.m., per McQ’s instructions. At 6 p.m., McQ took anti-nausea medication. Because the lethal drugs are so bitter, there is some chance patients won’t keep them down.

Four close friends gathered, along with Robinson. They sorted through McQ’s CDs, trying to find appropriate music.

“He put on Marianne Faithfull. She’s amazing, but, it was too much,” Robinson said. “Then he put on James Taylor for, like, 15 seconds. It was ‘You’ve Got a Friend.’ I vetoed that. I said, ‘Aaron, you cannot do that if you want us to hold it together.’”

DeRoche went into a bedroom to open the 100 capsules of 100-milligram secobarbital, one at a time, a tedious process. Then she mixed the drug with coconut water and some vodka.

Just then, McQ started to cry, DeRoche said. “I think he was just kind of mourning the loss of the life he had expected to live.”

After that, he said he was ready. McQ asked everyone but DeRoche to leave the room. She told him he could still change his mind.

“I said, as I do to everyone: ‘If you take this medication, you’re going to go to sleep and you are not going to wake up,’” she recalled.

McQ drank half the drug mixture, paused and drank water. Then he swallowed the rest.

His friends returned, but remained silent.

“They just all gathered around him, each one touching him,” DeRoche said.

Very quickly, just before 7:30 p.m., it was over.

“It was just like one fluid motion,” DeRoche said. “He drank the medication, he went to sleep and he died in six minutes. I think we were all a little surprised he was gone that fast.”

The friends stayed until a funeral-home worker arrived.

“Once we got him into the vehicle, she asked, ‘What kind of music does he like?’” Robinson recalled. “It was just such a sweet, human thing for her to say. He was driving away, listening to jazz.”

McQ’s friends gathered June 30 in Seattle for a “happy memories celebration” of his life, Robinson said. She and a few others kayaked out into Lake Washington and left McQ’s ashes in the water, along with rose petals.

In the months since her friend’s death, Robinson has reflected on McQ’s decision to die. It was probably what he expected, she said, but not anything that he desired.

“It’s really tough to be alive and then not be alive because of your choice,” she said.

“If he had his wish, he would have died in his sleep.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!