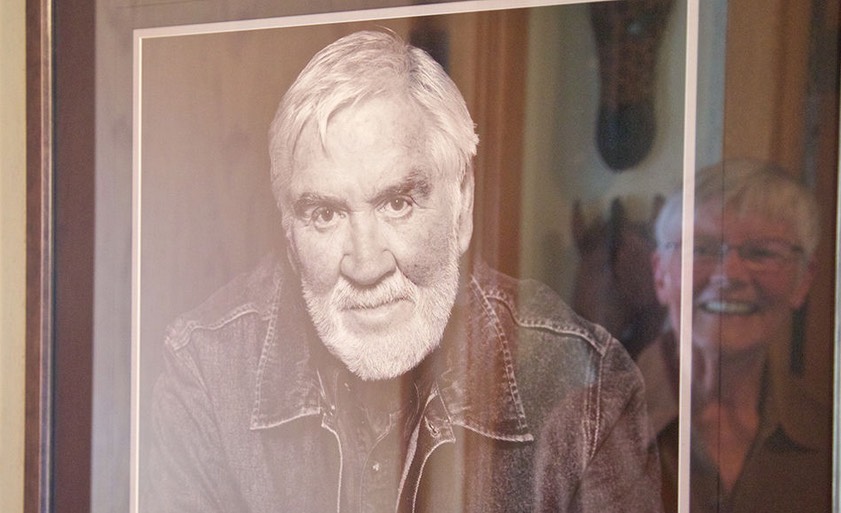

In this installment of NPR’s series Inside Alzheimer’s, we hear from Greg O’Brien about his decision to forgo treatment for another life-threatening illness. A longtime journalist in Cape Cod, Mass., O’Brien was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease in 2009.

These days, Greg O’Brien is thinking differently about the future. It’s been six years since his Alzheimer’s diagnosis, and he’s shared with NPR listeners a lot about his fight to maintain what’s left of his memory. He’s shared his struggles with losing independence, and with helping his close-knit family deal with his illness.

What O’Brien hasn’t wanted to talk about until now is the diagnosis he got two weeks before he and his family learned he had Alzheimer’s disease: O’Brien also has stage 3 prostate cancer. Now, as his Alzheimer’s symptoms worsen, the cancer is increasingly on his mind.

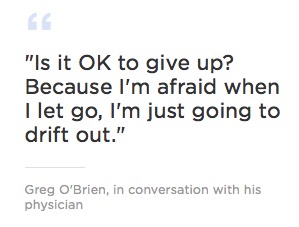

“I just don’t know how much longer I can keep putting up this fight,” he says.

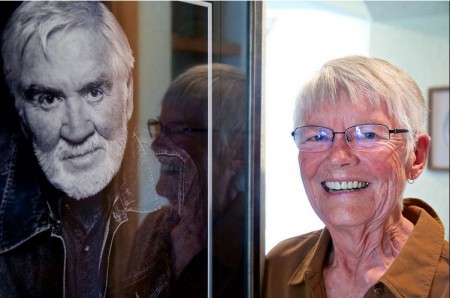

This summer, Greg and his wife, Mary Catherine O’Brien, have started talking about how he wants to spend the final years of his life — and what Greg calls his “exit strategy.”

He hopes the cancer will kill him before the Alzheimer’s disease completely robs him of his identity.

Recently Greg sat down with his close friend and primary care physician, Dr. Barry Conant, and with Mary Catherine, to talk about that decision and about Greg’s prognosis.

Interview Highlights

Dr. Barry Conant on the ethics of not treating Greg’s prostate cancer

I think honestly, in a perverse kind of a way, it gives you solace.

Maybe it will shorten the period in your life which you find right now to be something you want to avoid, and so far you’re only talking about neglect of a potentially terminal condition.

If you decided to be more proactive, that’s where the discussion becomes more interesting. Some people would say I’m violating  my Hippocratic oath by discussing that, but I think — I don’t feel uncomfortable having that discussion. And, while you still have the ability to reason, it wouldn’t be a bad discussion to have with your family.

my Hippocratic oath by discussing that, but I think — I don’t feel uncomfortable having that discussion. And, while you still have the ability to reason, it wouldn’t be a bad discussion to have with your family.

Conant — who, like O’Brien, has cancer — consoles Greg that his family will be OK

Nobody is indispensable — nobody. And if you or I were to immediately vanish from the Earth, our families would do fine. They have family support. They have friends’ support. They’re in a nice community. It’s a terrible sense of loss that they’ll have, but they will do fine. And if they’re honest with themselves, they’d realize that they’re going to do fine.

Greg and Mary Catherine discuss Greg’s prognosis

Mary Catherine: Going through Alzheimer’s, it’s not the plan.

Greg: Where do we go from here?

Mary Catherine: That I don’t know. …

Greg: It’s getting so frustrating for me. I mean I care, obviously, deeply about you and the kids. I could see 3 or 4 more years of this, but I can’t keep the fight up at this level. We talked about that the other night. How did you feel about that?

Mary Catherine: Wow … (chokes up). I don’t want to talk about it.

Greg: Can you see it coming?

Mary Catherine: Yeah, I can. Fast.

Greg: Are you OK with me not treating the prostate cancer?

Mary Catherine: Only because you’re OK with it. You need that exit strategy, and the exit strategy with Alzheimer’s is horrible. Well, they’re both horrible.

Greg: You know I’ve been there with my grandfather and mother, and don’t want to take my family and friends to that place.

Mary Catherine: Right. I know. I understand.

Greg: Do you still love me, dear?

Mary Catherine: Yes, I do, dear.

Greg: I love you, too.

Complete Article HERE!

Over the past year, I’ve experienced several losses that, at the request of the deceased, did not include funerals. Grief rituals are central to my mourning process, but there’s no negotiating with the dead. In the absence of the most standard of ceremonies, how do you give expression to your grief while respecting someone’s final wish for “no funeral, please?” Through personal experience, and conversations with friends and readers who’ve faced the same scenario, here are seven ways to do just that.

Over the past year, I’ve experienced several losses that, at the request of the deceased, did not include funerals. Grief rituals are central to my mourning process, but there’s no negotiating with the dead. In the absence of the most standard of ceremonies, how do you give expression to your grief while respecting someone’s final wish for “no funeral, please?” Through personal experience, and conversations with friends and readers who’ve faced the same scenario, here are seven ways to do just that.