The day he was to die, Vernon Gearhard had breakfast with Fran, his wife of 57 years, their three children and their spouses.

He listened to some of his favorite music – classical pianist Johannes Brahms and opera singer Kathleen Battle – and around noon, he and Fran sat on their terrace. The sun peeked out from behind rain clouds and two bald eagles and several raven flew around nearby, lingering in the area as the couple watched.

The 84-year-old master mason had planned for this day. Friends and family had been visiting for the past month, many from nearby towns, others from as far away as Vermont. He had spent the last week with his family, including his seven grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

It was time.

The medication – powder from 100 capsules of the barbiturate Seconal – had been mixed with water, creating a slurry-type paste that Vern could drink. He went into the bedroom and grabbed the bar he needed to use to pull himself from his wheelchair into a sitting position on the bed.

The medication – powder from 100 capsules of the barbiturate Seconal – had been mixed with water, creating a slurry-type paste that Vern could drink. He went into the bedroom and grabbed the bar he needed to use to pull himself from his wheelchair into a sitting position on the bed.

“This is the last damn time I have to grab this bar,” he told his wife, Fran.

He drank the medicinal slurry, washing it down with orange juice. His eyes rolled backward and he lay back on the bed. Thirty minutes later, surrounded by his family, his heart stopped beating.

“Just our children came in while he was dying,” Fran said. “I promised him that someone would be touching him the whole time.” She stayed with his body until the hearse arrived.

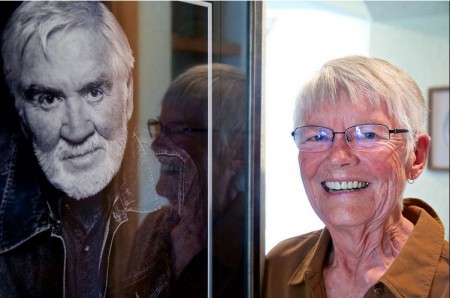

Fran remembers that day – March 17, 2015 – with tears and joy.

“It was so easy for him, finally,” she said. “It has been a long time since anything had been easy. … It was really a joyful thing.”

Vern, who had Parkinson’s disease, was given less than six months to live when he decided to end his life by taking prescribed medication through Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act.

On President’s Day, Feb. 16, 2015, Fran and Vern gathered their family together and told them of his decision. Their three children and their spouses were supportive. So was the rest of the family.

That support, Fran said, made it possible. “The kids really, really, really were there for us. I couldn’t have done it without their support.”

Since Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act was enacted in 1997 more than 860 terminally ill people have chosen to use it to end their lives. To do so, a patient must get the agreement of two doctors that he or she has six months or less to live. The patient also must go through an intensive interview process to determine his or her mental state and decision-making capabilities.

It’s not easy, Fran said, noting that the Gearhards had help from Compassion and Choices, a nonprofit advocacy group that provides trained volunteers and consultants to help terminally ill patients seeking end-of-life options. The Gearhards connected by phone with a Compassion and Choices volunteer in Ashland.

Vern was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease about 20 years ago, when he was in his early 60s though family members say he had symptoms of the disease, including tremors, in his late 50s. He took medication and led a physically active lifestyle, which seemed to keep the disease’s symptoms at bay.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive disorder of the nervous system that affects movement. It develops gradually, and early symptoms include tremors. In the later stages, muscle stiffness makes it difficult or impossible for patients to walk and take care of themselves.

Vern was born in Chicago, and grew up in Martinez, Calif. He joined the Navy and served in the Korean War from 1950-54. He then attended Cal Poly on the GI Bill and earned a degree in agronomy. Vern and Fran began dating while she was in college – she earned an education degree from San Francisco State University. They married her sophomore year in college. Several years later they bought acreage north of Merrill in 1965 and started farming.

Fran taught for 34 years, 28 of those as a fifth-grade teacher at Shasta Elementary in Klamath Falls. They raised three children – Theresa, Marcus and Paul.

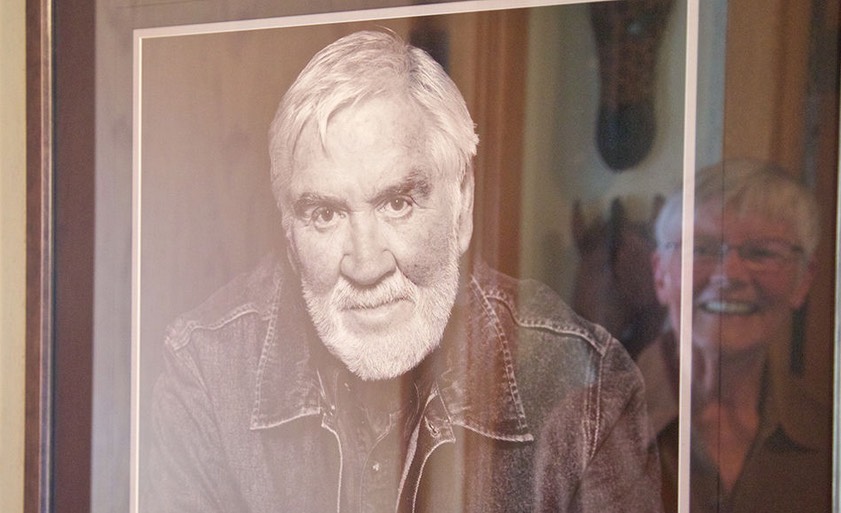

The family farmed for 15 years, but masonry was in Vern’s blood. His grandfather, an Austrian immigrant, was a mason and Vern apprenticed under him. As farming changed, Vern spent more time on masonry and eventually worked at it fulltime, earning a reputation as master mason with an artistic and signature style.

After his Parkinson’s diagnosis, Vern continued to work as a master mason, creating artistic fireplaces, homes and other pieces for private clients as well as for local businesses. Some of his more prominent pieces include the Klamath Rotary sign downtown, the sign at the Herald and News building off Foothills Boulevard and the rock sign at Kla-Mo-Ya Casino off Highway 97 near Chiloquin.

He helped build his house, high on a hill, an artistic nod to a mason’s mastery of his craft. Inside, a rock fireplace dominates the great room and touches of his work are throughout.

He helped build his house, high on a hill, an artistic nod to a mason’s mastery of his craft. Inside, a rock fireplace dominates the great room and touches of his work are throughout.

Vern loved classical music, opera, and good literature. He belonged to two book groups and owned the first version of Kindle, an electronic book reader that launched in November 2007. By the time he died, he owned his eighth Kindle.

He also was a huge San Francisco Giants fan. “He always recorded the games he couldn’t watch,” Fran recalled. “God pity you if you told him the score before he could watch it.”

When he was 80, his symptoms — tremors, muscle and balance issues — forced him to retire. The disease progressed quickly after he stopped working. First, he had to use a cane and later, a wheelchair.

As the disease progressed, Vern needed help with everyday tasks, and then could no longer use his hands well enough to turn the pages on his Kindle. In his last month, he was sleeping nearly 20 hours a day and had limited energy.

“When he had to quit work, that was huge. When he had to quit driving, that was huge,” Fran said. “When he lost the ability to read, that was it.”

In November 2014, Fran, 78, faced her own mortality when she was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer. She decided to go through treatment so she could be there for Vern, who was thinking about his end-of-life options. She had surgery, followed with chemotherapy in January, and currently is cancer free.

Vern approached his doctor, who said though he supported Vern’s decision, he couldn’t write the Death With Dignity prescription. His physician did prescribe hospice, which is for patients who have been diagnosed with six months or less to live.

The Gearhards were able to find two other Klamath Falls physicians who were willing to consider Vern’s decision and work with them. The law requires both a prescribing physician and a consulting physician to agree on a diagnosis and prognosis as well as whether Vern was mentally capable of making the decision to end his life.

Klamath Hospice helped with Vern’s care and supported the family during his last months of life. Hospice does not advocate for or against the Death With Dignity Act, but provides support for patients and their families, Fran said.

When the time came, the law required that Vern take the prescription himself, holding the mug and drinking the medication without aid.

“His big worry was that he would be beyond the point where he could do it on his own,” said Dennis Ross, Vern’s son-in-law. “Your ability to follow through could be ended at any time.”

Ross was there the day of Vern’s death. An hour before he was to take the prescription, he had to take anti-nausea medication. The medication made him sleepy and he told his family: “I’m getting sleepy. We better get on with it.”

Ross, who had watched his parents die, believes the dying should have choices. His parents lived in California and didn’t have the same end-of-life options Vern did.

He watched Vern’s quality of life decline and supported his decision. “There’re just a thousand little things that take your dignity away,” he said. “It just piles up.”

But the end game is up to the patient.

“You can make all the plans, but when it comes down to drinking that stuff, that’s an incredible amount of courage,” Ross said.

Vern’s memorial was March 21 at his daughter’s home, a rock house he helped build near his own, and cars lined the road as family, clients and friends came to celebrate his life. Vern had picked the music he wanted played at his funeral – Mozart’s “Concerto in D-Minor, Second Movement” and John Lennon’s “Imagine.”

The Concerto in D-Minor was a piece Vern fell in love with in 1981 while he was collecting rock in Langell Valley. “He always listened to classical music while he worked,” Fran said. “That day he came home and said, ‘This is what I want played at my memorial.’ Before he died, he played it for his friends who came to visit, and for the hospice worker.”

Vern was an atheist and was curious about death.

“He always said he wanted to know so he wanted to be aware,” Fran said. “He was always very articulate about his perspective of life and death.”

“For us and for Vern – it was his decision – it was right,” she added. “It’s not for everyone, I understand. I just want to share the opportunity this law gave us.”

Fran recalled her husband’s last hours with joy.

It was around noon, just before the two of them went to sit on the terrace.

“Vern started to sob, and I asked, ‘What’s going on?’ He said, ‘I just feel so much love.’”

Fran smiled. “It’s a story with a beautiful ending.”