Couple talks joys of raising son with Down syndrome, challenges of early aging

Tom and Rosemary Ryan’s story parallels the story of Down syndrome these past 59 years.

Not only has the Orland Park couple lived the joy, challenge and learning curve that accompanies raising a child with special needs, they’ve dedicated their lives to pioneering change in governmental support, educational opportunities and societal views.

“A lot has changed over the years,” Rosemary said. “We’ve come a long, long way.”

Like many parents of special needs children, love thrust them into the world of advocacy. When there was no preschool for their son, Rosemary started one. When the concept of housing adults with Down syndrome in group homes instead of institutions was proposed, they jumped on board — landing smack in the center of a national debate and garnering the attention of ABC-TV’s “Nightline” with Ted Koppel.

And, now, as their oldest son endures perhaps the cruelest of characteristics often associated with his condition — accelerated aging — the Ryans are again at the forefront of the discussion.

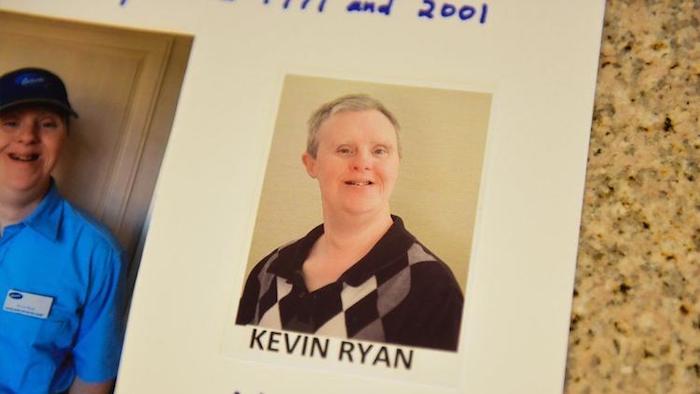

Kevin Ryan is 59 but a checkup last spring revealed “he’s more like going on 70,” Rosemary said. “He’s gonna pass us up.”

Raising a child with Down syndrome is “perpetual parenthood,” Rosemary said, “if you are committed to wanting the best for them.”

Now in their 80s, the Ryans, who live at Smith Crossing retirement community, are simultaneously discussing end-of-life care for themselves and for their son.

Into the light

When Kevin Ryan was born Aug. 4, 1959, Tom and Rosemary felt the way many parents of newborns with special needs felt back then — alone. The support and advice that today are showered upon parents of babies born with Down syndrome was nonexistent then, Rosemary said.

Three pediatricians examined Kevin and agreed he had the condition characterized by an extra chromosome.

“They called it ‘Mongolism’ back then,” she said.

In those days, there were no prenatal tests to predict it, nor any way to prepare for it, she said.

“We didn’t expect an anomaly with our first baby, but it was meant to be,” Rosemary said.

The “new” thinking at the time was that the couple should take their newborn home, she said.

And that’s where the advice ended. Rosemary could find only one very dated guidebook at the library that she said was so negative, “I couldn’t get past page three.”

So she relied on her instincts and on training she’d received en route to becoming a pediatric nurse to get through the early years, she said.

“And we just kind of forged ahead,” she said.

The Ryans went on to have three more children, with their second son quickly passing his older brother developmentally. Rosemary gave up her nursing career to stay home and care for the children.

Testing had revealed that Kevin was on the border of EMH (educable mentally handicapped) and TMH (trainable mentally handicapped), she said.

Those terms have fallen from the lexicon, along with “Mongolism,” but what Kevin’s score meant, Rosemary said, was that he’d struggle in an academic program, but likely excel in a training setting. They chose the latter.

“Back in 1962,” she said, “public schools had EMH but no TMH.”

The Ryans were living in Jacksonville, Ill., then and Rosemary and another mom decided to start a school in a nearby church. They set up an advisory board with a host of professionals and townspeople, and hired two teachers.

Kevin attended for a year and a half, until Tom, who had given up teaching high school to work at State Farm Insurance, was transferred to the south suburbs.

Changing laws, changing attitudes

While Rosemary had been organizing a school in central Illinois, other parents were doing the same in Chicago Heights. In 1965, after the Ryans moved to Park Forest, Kevin began at privately run Happy Day School.

Ten years later, Public Law 94-142 mandated public school be available to all kids ages 3 to 21 (later extended to age 22), and Kevin transferred to SPEED Development Center in Park Forest.

SPEED, Tom said, “was the creme de la creme” and Kevin continued there until he turned 21 and returned to Happy Day for adult workshop.

The end of public school life often is a time of great concern and confusion for parents of children with special needs, Tom said, particularly if they haven’t planned ahead.

“Some people choose to have their adult kids just stay home,” Tom said, but that can lead to problems if the parents’ health begins to fail.

Kevin continued attending workshop at Happy Day and living with his parents until 1995.

NADS

Down syndrome is the most commonly occurring genetic condition, said Linda Smarto, director of programs and advocacy at the National Association for Down Syndrome in Chicago.

Approximately 6,000 babies with the condition are born each year in the United States, Smarto said. That translates to 1 of every 730 live births, a number that seems to be on the rise, she said.

“When my daughter was born 24 years ago, the number was 1 in 1,200,” she said.

“Eighty-five percent of (these) children are born to moms 35 years old and younger,” she said. “So it’s a great myth that (Down syndrome) only occurs to parents who are older.”

While individuals with the condition develop more slowly at the beginning of life, the end of life seems to rush at them. Not everyone with Down syndrome is afflicted with premature aging, Smarto said, but there does seem to be a precursor to that and Alzheimer’s disease.

“Down syndrome, (researchers) say, will find the cause for Alzheimer’s because (scientists are) really pushing to find some sort of a cure and learn why this is happening,” Smarto said.

The phenomenon can be heartbreaking for loved ones already wrestling with end-of-life care decisions. What to do with aging children who have Down syndrome is a huge concern, Smarto said, especially if the individual has medical issues.

But, she added, it’s the same concern for anyone with a disability. And it’s the same for elderly adults who don’t have a living child to help care for them, she said.

If a sibling or other family member isn’t available to assist, an individual may be placed in a state-run home. “Our goal is to have our individuals either live independently or with a family member,” she said.

Smarto said most of NADS referrals come from the south suburbs.

“We don’t really know why the occurrence of Down syndrome is a little more prevalent there. (Advocate) Christ delivers about 4,000 babies a year and we get a lot of referrals from there. But it’s also a higher level hospital that sees patients who need special care. And they have a special care nursery,” Smarto said.

“But it is interesting the statistics (when compared) to (Northwestern Medicine’s) Prentice (Women’s Hospital in Chicago), which delivers 10,000 babies a year and the commonality is not as much,” she said.

Smarto said much of the evolution of Down syndrome inclusion is owed to parents like the Ryans, moms and dads who’ve helped usher in change by volunteering, serving on boards and doing the work. Many of the improvements in the special needs community, she said, is credited to parental advocacy.

15 minutes

In the early 1990s, a group out of Galesburg came to Happy Day, now called New Star Services, and told parents they were going to start building group homes in neighborhoods, Tom recalled.

It was a new concept sweeping the country, he said, and they had found a lot on Broadway in Chicago Heights.

The Ryans were among several parents who signed on. At the time, Kevin was 31 and eager to get out on his own, Rosemary said, because his younger siblings had flown the coop.

But the city of Chicago Heights fought the idea and became “the test case for the nation,” she said.

“Chicago Heights took on the federal government,” she said. “Who do you think won?”

The battle introduced many to the acronym NIMBY (Not in My Backyard) and made national headlines. A photographer from U.S. News and World Report visited the Ryan’s home and a picture of Kevin ended up on “Nightline,” Rosemary said.

The city lost and had to pay the agency and the prospective residents, she said.

“Kevin got his check for $1,000 and we took him to Hawaii,” Rosemary said.

Early aging

In 1992, the Adult Down Syndrome Clinic opened in Park Ridge. Run by NADS, the facility introduced the Ryans to Dr. Brian Chicoine, and what Rosemary calls “a world of support.”

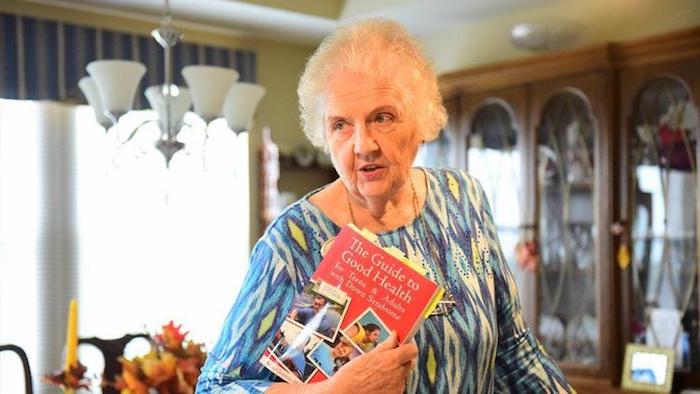

Rosemary calls Chicoine’s book, “The Guide to Good Health for Teens & Adults With Down Syndrome,” the “Dr. Spock for parents of kids with Downs.”

Kevin continues to see Chicoine — these days for premature aging symptoms. His hearing is declining, he’s having trouble with his teeth, he walks with a cane, Rosemary said.

In 2012, fearing their son might encounter early aging issues down the line, the Ryans moved Kevin out of the group home and into Good Shepherd Manor in Momence.

“We got to thinking, if he was left in a group home environment and his physical or mental health declined, their only option is to put him in a (Medicaid) nursing home,” Rosemary said. “We didn’t want that.”

Good Shepherd Manor, Tom said, is the closest thing to a forever home. It serves 125 adults, many of them aged.

“They’re committed to lifetime care, no matter what happens,” Rosemary said. “If he gets dementia, if hospice is needed, they’ll take care of it.”

Now, Rosemary said, Kevin’s lifestyle mimics that of his parents. “We have every level of care we’re ever gonna need here (at Smith Crossing), and so does he there,” she said.

The Ryans’ other children are scattered from Maine to Hawaii, with Kevin’s closest sibling living 1,000 miles away, so, Rosemary said, “If Kevin outlives us, we’d like him to stay at Good Shepherd because that’s what he’s familiar with.”

Raising Kevin has always been about choosing the best path for him, Rosemary said.

Special needs can mean special, or additional, considerations, she said, but the condition can also bring a special kind of joy.

Their son has had many positive life experiences, including participating in Special Olympics, attending Prairie State College, serving as a church usher and holding several jobs in the community.

“He’s truly been a joy,” Rosemary said. “But it is hard watching him age. You almost forget you’re a senior citizen because you’re taking care of a senior citizen.”

Kevin, she said, “is still funny. He’s still a character. He still steals the limelight at family get-togethers.”

And, Tom said, a quiet day is when Kevin calls only two or three times on his cell phone.

“In a way,” Tom said, “he is sort of the person who ties our family together.”

Although Dr. John Langdon Down first identified the condition marked by an extra chromosome in 1866, it wasn’t until the 1970s that “Mongolism” was renamed Down syndrome.

“Some people,” Rosemary said, “like to call it ‘up syndrome,’ because the people who have it are more up than down.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The End-of-Life Care That Veterans Need

How to ensure comfort and dignity come first

Every veteran is unique, with a lifetime of memories, stories and achievements. At the same time, veterans share a common experience regardless of when and where they served. The rigors of military training, the bonds developed among service members, long separations from family and loved ones and the severe stress of combat all form a veteran’s character. It’s common for intense emotions and memories to resurface at the end of a veteran’s life, sometimes to the surprise of family members who are hearing these things for the first time.

Physical, Emotional and Psychological Pain

The harsh toll of war includes disease, disability and illness that can complicate end-of-life care. Depending on the war, veterans may have been exposed to ionizing radiation, Agent Orange, open-air burn pits, battlefield transfusions, below-freezing temperatures and infectious diseases. These exposures put them at a higher risk for a variety of cancers, Type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, heart disease, hepatitis C, respiratory illnesses, malaria, tuberculosis and more.

Symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can arise at the end of life, even if they weren’t present before. Sometimes clinical symptoms can mimic those of PTSD, including traumatic recollections, flashbacks, hypervigilance, hyperarousal and agitation and nightmares. These symptoms are often prompted by an emotional or traumatic experience such as receiving a terminal diagnosis.

In addition to physical and psychological conditions, veterans might feel like purging themselves of memories by discussing their military experience with others — sometimes for the first time. Veterans can also have concerns about how their families will manage after the veteran dies.

Navigating End-of-Life Needs for Veterans

At VITAS Healthcare, a provider of end-of-life care, we have extensive experience with veterans. We witness every day veterans exhibiting clinical and psychosocial issues more often than other hospice patients. We want to make sure our veteran patients feel safe and secure, and that’s why it’s important to acknowledge veterans’ emotional concerns, not dismiss them. Even if they are only memories, they are very real to the person experiencing them.

When caring for veterans, it’s important to respond appropriately to challenging clinical issues while placing patients’ feelings of comfort and security first. Veteran volunteers, who are veterans themselves, can play a valuable role by listening, understanding and empathizing in ways even family members sometimes cannot.

Honoring Veterans at the End of Life

One method to connect with veterans and ensure their comfort and dignity is to provide them with information on their benefits. Identifying potential entitlements and coordinating with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), service members’ agencies and other local and state organizations can be extremely helpful to veterans and their families who may not realize how to acquire the benefits they have earned.

It is also key to remind veterans they have a support system and that they are valued. Some veterans returned from war without even receiving a “thank you for your service.” Giving veterans the recognition they deserve can make a world of difference.

Something small like offering veterans a recognition ceremony honoring their military service can go a long way. It can happen quietly, right at the bedside.

Additionally, the nonprofit Honor Flight Network sends veterans from around the country to the nation’s capital at no cost to visit and reflect at their war memorials, which is typically a very meaningful and special experience for veterans.

When veterans are unable to make the trip due to mobility issues or terminal illness, there are other options.

In some states, Flightless Honor Flights take place in a large room decorated by the community to resemble an airplane. With a video presentation played on a large screen, patients experience an Honor Flight without having to step foot on an actual plane.

In addition, Virtual Honor Flights are ideal for bedridden veterans. We’ve purchased virtual reality headsets with pre-recorded, 360-degree tours recorded by retired military tour guides, of the World War II Memorial, Korean War Memorial, Vietnam War Memorials, Women’s Memorial and Arlington National Cemetery.

Veteran patients and their families should know they are never alone. From challenging clinical symptoms to complicated benefits issues to a simple “thank you,” veterans should feel supported. It is never more important than at the end of life to show veterans unwavering honor and respect.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How to Deal With a Bereavement As a Teen

Dealing with a death as a teenager can be extremely hard. Many teens have lost loved ones, so you aren’t alone!

1

Never be afraid to cry. Crying is good for you. It helps you let go of some of the hurt or anger you may have. You shouldn’t feel weak or silly while crying. After all this shows that you loved the person and that they were important to you.

2

Talk to someone you trust. This could be a parent or guardian, your best friend or if you are religious, a pastor or priest. Talking about the one you loved can help you remember all the good memories you have had with them.

3

Help yourself to remember them. Listen to their favorite songs, look at pictures, read their favorite poem, plant their favorite flower in your garden. This is a good thing as it means you still have a small part of them with you.

4

Don’t blame yourself. This is a common reaction to the death of a loved one, but remember they wouldn’t want you to blame yourself.

5

If you are religious, find comfort in the fact they have gone to a better place. Remember that they are more peaceful, and there is no more hurt or pain were they are now.

6

Visit their grave site. This can bring some comfort as you can take care of their grave site. If you do not like visiting a resting place it does not mean you are a bad person, they would understand that maybe you don’t want to remember them that way.

7

Pray. Sometimes it can sound silly but if you are religious or even if you aren’t this can bring a lot of comfort as you feel closer to the person, you can talk to them and ask them to watch over you and keep you safe.

8

Have some alone time. Time on your own can help you get your thoughts together. Sitting in silence for a while can be quite comforting and can help you feel better.

9

Remember the person how you want to. Do not let other people tell you how to remember the one you loved. Remember them however you want. Your love for them could have been different than others.

10

Remember that they loved you. They always will and by feeling pain this shows you also loved the person.

11

Say goodbye. Say it however you want. Scattering the remains in a place they loved can bring some closure, also having a service can help you say goodbye.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

When Patients Can’t Be Cured:

Mass. Med Schools Teaching More End-Of-Life Care

By Kathleen Burge

On the second day of her geriatrics rotation, Jayme Mendelsohn buckles herself into the back seat of her professor’s blue minivan and rides south from the Boston University School of Medicine toward the house of a patient who cannot be cured.

As they drive through Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan, the professor, Dr. Megan Young, briefs Mendelsohn and another medical student about the elderly woman: She is 98, and diabetic, with increasing dementia.

She struggles to walk even a few steps, and can no longer make her way down the long cement stairway to her driveway. She has been housebound for nearly two years, and has a beloved dog who climbs up on her bed.

Young could have ordered tests, requiring hospital visits, to figure out why the patient had trouble walking. But that wasn’t what the woman wanted. “Really, what she wants to do is stay home and work on her word puzzles and not go to doctors’ appointments,” Young tells the students.

In her first three years of medical school, Mendelsohn studied blood and bones, cancer and heart failure and diabetes, learning to fix the many ways a human body can falter and break. But now she and the other fourth-year student, Nirupama Vellanki, are learning how to be doctors in a new age in health care, as clinicians increasingly grapple with how medicine can help patients with incurable illnesses.

Last year, all four medical schools in Massachusetts agreed to work together to improve the way they teach students to care for seriously ill patients, especially near the end of life. This fall, the schools are gathering data on what students are currently learning about end-of-life care, and some are beginning to change the way they teach.

Students at UMass Medical School are learning to treat gravely ill patients in the school’s simulation lab, examining “patients” — paid actors — and talking to them and their “relatives” about their worsening illnesses.

At Harvard Medical School, professors also hope to add lessons about end-of-life wishes to the school’s simulated teaching sessions.

At BU, students are visiting patients with a hospice nurse for the first time this year. Fourth-year students like Mendelsohn and Vellanki will be questioned on the principles of palliative care — a medical specialty that seeks to improve seriously ill patients’ quality of life — that they’ve learned on rotations like Young’s, part of the effort to measure what they’re learning.

“We are taught to solve problems, fix them and move on,” Mendelsohn says. “But that is not the answer all the time.”

In the United States, the richest country in the world, many of us live poorly at the end of our lives. We don’t talk enough with our doctors about what we want — what’s important to us — if we become seriously ill and cannot be cured. For instance, although most of us say we want to die at home, only about one-fourth of us do. And doctors have traditionally been given little training in how to talk with ill patients about dying.

“There’s a lot to be proud of in modern medicine,” says Dr. Jennifer Reidy, chief of the palliative care division at UMass Memorial Medical Center and an associate professor at UMass Medical School. “But there is a bit of a steamroller effect sometimes in health care. There is a momentum towards doing more because we can, and we know how to do it.”

The new end-of-life training for medical students grew from the Massachusetts Coalition for Serious Illness Care, a group created in 2016. Surgeon and writer Atul Gawande, one of the coalition’s co-founders, asked Harris Berman, dean of the Tufts University School of Medicine, if he would bring together the state’s medical schools to improve training in palliative care.

The other deans agreed. All of the schools had some teaching on palliative care, but believed they could do better.

“If we’re not teaching it, if we’re not testing it, the message is that it’s not part of their job,” says Kristen Schaefer, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. Instead, the professors at the four medical schools want to teach students early on how to help gravely ill patients, she said, so they understand: “This is part of what it means to be a doctor.”

The schools won’t adopt the same curricula — the medical schools vary in size, budget and curriculum — but they will train students in five basic elements of palliative care. Patients do not have to be dying to receive palliative care, which can start anytime after diagnosis, including during treatment.

Learning how to talk to seriously ill patients and their families lies at the heart of the curriculum changes. Students will be taught how to discuss not only the science of their patients’ illnesses but also their patients’ wishes and values, and help them create plans for treatment.

“These are extremely challenging conversations,” says UMass Medical’s Reidy. “They’re very emotional. There is a framework, a cognitive map, but ultimately it’s [like] jazz. It’s whatever’s in the moment.”

Students will be taught to anticipate strong emotions and how to talk to patients who are deeply sad or angry.

“Students are afraid that they’re going to say something wrong that could hurt patients and families,” says Schaefer, also a palliative care doctor at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “They feel worried that they’re going to cry themselves, that they’re not going to know what to do.”

The medical schools also hope to head off burnout, a serious problem for doctors, by teaching students to pay attention to their own emotions, and relaying coping strategies for working with dying patients.

‘Create A Good Death’

Young’s patient, Ellen “Nellie” White, lives in Hyde Park with her daughter, Christine. Young, a home care physician at Boston Medical Center, began treating her a year ago.

“So Mom, this is the doctor I told you about coming today,” Christine says, opening the door to her mother’s bedroom, just off the kitchen. Young and the two students trail behind her.

Ellen White, born nearly 99 years ago in Ireland, sits on an easy chair with a green crocheted blanket across her legs. Her gray hair is cut short. Her daughter moves a book of word puzzles from her mother’s lap onto a table.

White squints up at her visitors. “Let me put on my glasses so I can see you,” she says.

“My name is Jayme,” Mendelsohn says loudly, so White can hear her. “I want to know how you’re feeling today.”

“I’m feeling fine, thank God,” White says. “I have no complaints.”

“Is anything bothering you?”

“Nope.”

Mendelsohn asks her a few more questions. She turns to her professor.

“Dr. Young, is there anything else you want us to specifically chat about today?” she asks.

Young asks her to check White’s blood pressure and listen to her heart and lungs.

White’s blood pressure is excellent. Mendelsohn takes off her watch.

“Let me just check your pulse,” she says.

She lays a finger across White’s wrist and gazes at her watch.

“Am I alive?” White asks.

Mendelsohn, counting, doesn’t answer. A few seconds later, she tells Young the pulse is a little more than 100 beats per minute.

“You’re alive!” Young tells White.

“That’s good to know,” she says.

Vellanki gives White a flu shot. The doctor and students leave the house. Afterward, the medical students say these visits help them learn different purposes of medicine.

“It can be really important for a medical student to have that moment where your job right now is not to write 15 different notes and to do all these different things and to solve their hypertension,” Mendelsohn says. “Your job is to talk to the patient and see what they need. … There are lots of times in medicine where you can’t solve the problem because the problem is bigger than medicine.”

Vellanki says she’s learning that doctors can still help patients at the end of their lives.

“I think you can’t solve the problem of dying but you can create a good death,” she says. “And that’s something that I don’t remember being taught much in med school.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

My odd job:

Working in cremations has taught me how important it is to make the most of life

By Catherine Powell

I usually get one of two reactions to my work as a cremation provider – either total fascination or a horrified escape to the other side of a room.

There’s a lot of misunderstanding about funeral work, but it’s really all about people.

My husband and co-founder of Pure Cremation has been in funeral service for over 30 years, and I became a funeral arranger then a funeral director thanks to him.

Some do find it shocking that, as a woman, I have personally collected the deceased but, in reality, my job gives me the opportunity to make a real difference to people at a crucial moment in their lives, and even to delight them.

While many people are quite squeamish about the idea of the job, I assure you the jokes are worse.

When you get into the industry, I think you need to be prepared to hear, ‘That’s a dying trade isn’t it?’ or ‘You’ll never go out of business!’ – but it’s all part of the job.

We give simple, dignified care to the person who has died, including collecting them from their place of death and getting them to the crematorium, where they will have an unattended cremation.

Compared to traditional funerals, there are a few key differences with the type of cremation we do.

We never embalm the deceased – it isn’t necessary because of temperature controlled facilities.

We also use a metal detector wand to quickly check for any implants that the family, and even doctors, are unaware of – several types can be hazardous during cremation. For example, pacemakers explode violently and so need to be removed before cremation.

Understandably, human cremation is very tightly regulated, with each person cremated individually, and the handling of the ashes is strictly monitored to avoid mix-ups.

To make sure there are no mistakes, everyone we look after gets a wristband with a unique identifying code that’s also displayed on the coffin lid, any jewellery bag and the ashes container.

Once checked and identified, each person is gently placed, just as they are, into an eco-coffin, which is made from natural, untreated pine, and is much more dignified than the typical mortuary tray where the body is exposed.

When all the paperwork is complete, the coffin is taken to a licensed crematorium.

The vast majority of our families don’t attend the committal at all, but a few do.

On these occasions, there can be just a handful of people in the room, which can be very moving indeed, and I consider it a real privilege to be a witness to these goodbyes.

Some of them are very emotional, particularly if the deceased is young or the circumstances of the death were tragic, but I’ve seen laughter and gratitude as well as tears.

Once the coffin is transferred into the crematory – a superheated furnace with space for just one body – the cremation itself can take up to 2 hours to complete.

Afterwards, any metal parts such as as surgical pins and joints are removed, and the remains are processed to a fine powder to make the ashes that people are familiar with.

The final stage of our care is the hand delivery of the ashes to the family, so that they can be laid to rest somewhere special, and there’s often a memorial service with the ashes instead of the coffin as the focal point.

Cremation actually allows people to better celebrate someone’s true personality separately and the send offs can be very unique, like burning arrows and Viking costumes.

There are two particularly surprising and lovely things that I remember.

The first was watching two daughters dance and play air guitar to Spirit In The Sky in the crematorium chapel as they said a private goodbye to their dad.

I was also able to give a terminally ill lady some joy, just by agreeing to include the ashes caskets of her beloved dogs in her coffin. Sadly, she passed a few weeks later.

It is moments like these that you see how people respond to a tragic event, and this is uplifting and inspiring in equal measure. These instances make me love my job.

I see my job as looking after the living, through excellent and compassionate care of the dead.

We’re here to support families through a traumatic event, and we see first-hand the extra worry that comes from having no idea what their relative wanted.

I’ve always believed that talking about our own end and arranging our own funerals makes a positive difference when it matters most. And it can be a really liberating experience!

This job certainly teaches you about life and how important it is to make the most of it. I’ve also learned what a difference it makes to leave a few clear instructions for your funeral, so your family can feel they ‘got it right’.

The families we look after are doing exactly what mum or dad asked for: a no-fuss, low cost funeral that leaves more to spend on the celebration of life, or to a good cause.

While a qualification isn’t necessary in the UK for a job like ours, great attention to detail, superb listening skills, and problem solving – whether practical or emotional – are essential.

Pay-wise, our drivers get a basic salary of more than £18,000 and lots of overtime on top!

The administration team salaries start at around £24,000, both are considerably higher than traditional funeral firms, where the starting salaries for a funeral arranger can vary between £15K to £19K.

Admittedly, direct cremation is not for everyone.

However, we do make a real difference, offering a liberating alternative that’s perfect for anyone who doesn’t want a traditional funeral.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

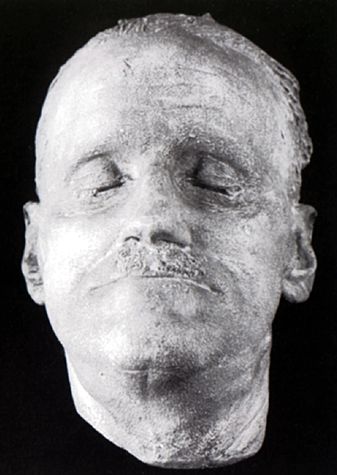

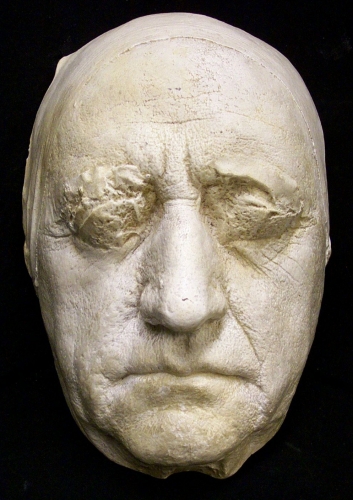

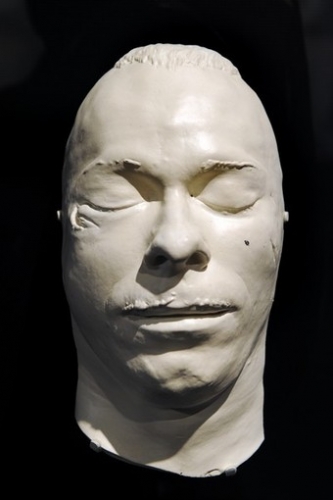

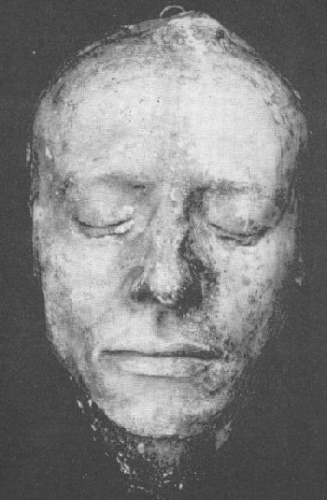

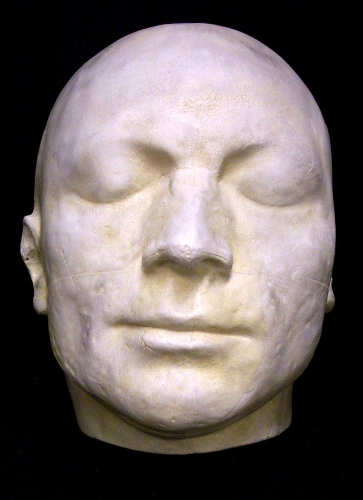

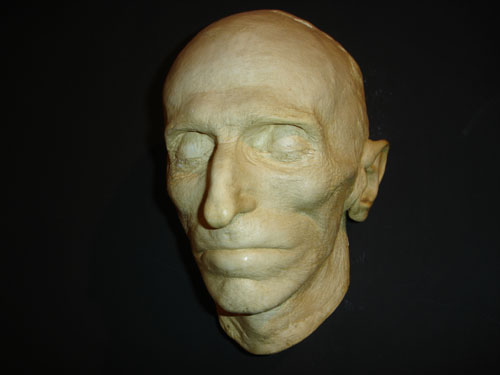

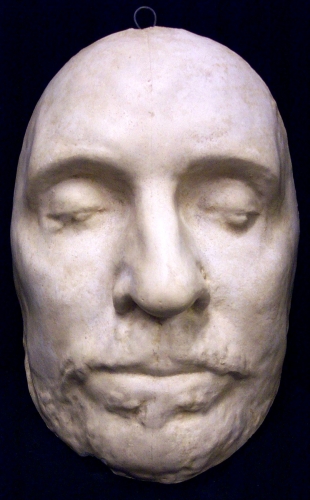

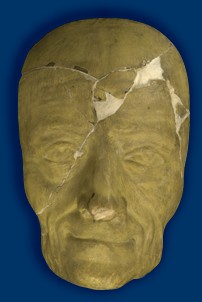

20 Death Masks Of Famous People

Learning To Grieve:

The Show Making Millennials Talk About Death

By Natalie Gil

Death is one of life’s few inevitabilities (along with taxes) but despite its certainty, dying and how we deal with it are still taboo topics in many countries.

A new BBC Three documentary explores how millennials grieve and how we can learn to do it better. Fronted by the presenter and musician George Shelley (of X Factor, Union J and I’m A Celebrity… fame), Learning To Grieve features intimate discussions with his family and friends about dealing with grief in the aftermath of his 21-year-old sister’s sudden death in a road accident in May 2017, alongside a broader look at how younger generations cope with grief and its impact on wider society.

He meets several other young people who have experienced loss to get advice and guidance about coping with grief in 2018.

Research has linked bereavement to increased rates of suicide and mental health problems among young people, and Learning To Grieve explores this connection head on. Shelley discusses his own use of antidepressants and experiences of therapy since his sister’s death, and the tough time he had in the immediate aftermath. “My days were just a blur of takeaways, Netflix and escaping with video games – anything to shut off from the real world,” he wrote about the experience recently. “All I can remember from that period is darkness and I just sank deeper into depression.”

What on earth are you meant to do when your mum has just died? I had no idea – so I carried on as if everything was normal.

One millennial featured in the documentary is Beth Rowland, 24, who lives in Nottingham. She lost her mum to liver cancer in July 2015 after her second year of university. She describes feeling like she was “stumbling around in the dark, with no idea what to do or how to function” in the aftermath, but she does remember very clearly going for a haircut just hours after it happened.

“I had it booked, had been looking forward to getting a new style, and I had no idea how to call the hairdressers to cancel my appointment,” Rowland told Refinery29. “So I went along, sat in the chair and answered ‘fine, thanks’ when the hairdresser asked how my day had been. That’s a perfect example to me of how confusing bereavement is, and often how ridiculous it can be. What on earth are you meant to do when your mum has just died? I had no idea – so I carried on as if everything was normal.”

Rowland got involved with the documentary to prevent other young people from plummeting to “the bad place” she was in, she said. Not only is bereavement normal, but so many people know exactly how you’re feeling. “When I lost my mum, I didn’t think I knew anyone who had been bereaved, but there were actually a lot of people already in my life who had been through the same pain. Unless we talk about loss, it will continue to be something people hide away, don’t know how to talk about, and that ultimately can lead to an increase in risk of mental illness.”

She believes everyone in the UK finds it difficult to talk about loss (because of our ingrained “stiff upper lip” culture), but younger generations struggle most and particularly those who have lost parents. “It’s not normal to not have a mum at 20 – all my friends flock to social media on Mother’s Day to share that their mum is the best mum, friends get married with their mum next to them, others say they couldn’t possibly have become a mother without their own mum beside them.” This, she believes, is why so many young people find it hard to talk about losing family.

In 2015, Rowland set up Let’s Talk About Loss, the UK’s first support network for young people aged 16-30 who have been bereaved. “I knew that to get through my experience, I had to do something proactive and positive that would make the world a little bit better. I felt so alone and confused when we lost Mum, and was diagnosed with severe anxiety and depression in 2017 after bottling up my feelings for too long. I’m not ashamed to say that my mental health was very bad and at one time I was considering suicide – I just didn’t know how to live without my mum. I’m in a much better place now but I’m only too aware how easy it is to struggle when you’ve been bereaved.”

You might have thousands of Twitter followers but be sat alone at home on a Friday night, feeling completely isolated.

Young people are increasingly talking openly about their feelings, in part due to the gradual falling away of the stigma surrounding mental health, and very often they’re doing it on Instagram, Twitter, Tumblr, blogs and other online spaces. This is progress, of course, but Rowland is concerned that talking online doesn’t eradicate the loneliness issue. “You might have thousands of Twitter followers but be sat alone at home on a Friday night, feeling completely isolated and without any form of support network.” Which is why Let’s Talk About Loss holds monthly real world meet-ups, as well as offering online support, which enable attendees to “talk openly about grief wherever and whenever we feel ready and comfortable.”

Rowland’s advice to other young people currently grieving is always to find their support network. “It doesn’t matter who they are, just find people who care about you, will be there for you when you need them, and who will let you talk.” She also recommends contacting local and/or national support groups and charities like Mind, Young Minds, Student Minds, Cruse and Widowed & Young. “However you are feeling, however bad it might seem – you are not alone and you can get through this, I promise.”

George Shelley: Learning To Grieve is available to watch on BBC Three from Sunday 30th September.

If you or someone you know is struggling to cope with grief, contact the bereavement charity Cruse online or over the phone on 0808 808 1677. You can also contact Rowland’s support network for young people, Let’s Talk about Loss, via email at hello@letstalkaboutloss.org.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!