Go funeral dress shopping. When the saleswoman asks about the event, say: “Dressier than office, but not as fun as cocktail.”

By Caroline M. Grant

Before: Text your friends to tell them that your mother has entered hospice. Tell them that it’s just to get the equipment she needs (a hospital bed, a better wheelchair) and not a sign of her impending death. Pretend you believe it.

Brace yourself for the SWAT team of hospice services and providers that descends on you: the social worker, the nurse, the chaplain, the volunteer bearing a soft blanket, a stuffed bear and lavender-scented hand lotion. Give the bear away.

Answer every phone call from “Unknown Number” because usually it is some kindly person from hospice. Apologize to the Unknown Number who is not hospice when you tell her no, you can’t subscribe to the symphony because your mother is dying. Start to tell her that your mother used to subscribe to the symphony and you would like to someday, when she is … Trail off, hang up and feel guilty about the little bomb you dropped into her day.

A month before your mother’s death, read the draft of her obituary that your father has written, and start to offer edits like it’s any other piece of writing. Don’t cry until you come to the names of your children and nieces.

Nine days before her death, lean in close to your mom, sitting in her wheelchair at the dining table, and ask her to repeat herself until you hear her say, “I’m hurting.” Take her back to bed immediately and tell her you’re sorry, so sorry, you never want her to be in pain.

Cut up the back of all your mother’s nightgowns so that the caregivers can take them on and off easily. Cut off all the buttons to make the gowns more comfortable.

Talk and text with your siblings to help them figure out if and when they should fly out. Tell them not to feel guilty if they can’t; mean it. Feel relieved when they all book flights.

Sit at your mother’s bedside, holding her hand and begging her to please hang on, when your sister’s flight is delayed for six hours. Keep readjusting the sleeping arrangements in your house so that two guest rooms work for five extra family members. Put air mattresses on the floor of your bedroom for your kids and secretly wish it were a permanent arrangement.

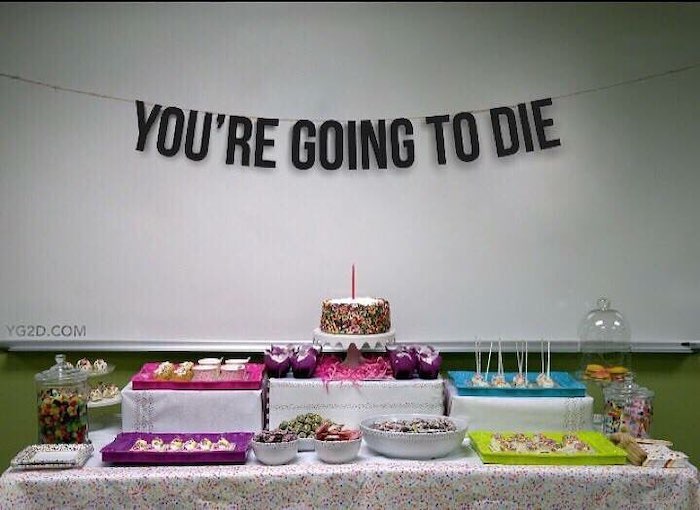

Go funeral dress shopping with a friend. Meet her after work downtown and go to the mall like it’s a normal evening. Feel momentarily stumped when the young saleswoman asks brightly, “Shopping for an event?” Resist the urge to answer darkly; instead, try, “Dressier than office, but not as fun as cocktail.” Stare back at the saleswoman and feel some sympathy when she blinks.

Buy an entirely inappropriate, form-fitting, off-the-shoulder dress (which will hang in your closet, unworn, until you finally take it to a consignment store). Accept your tissue-wrapped purchase from the saleswoman who says, “Have fun at your event!”

Escape with your friend to a restaurant and down a glass of wine, very fast.

Seven days before her death, stand at your mother’s bedside while a priest gives her the Last Rites. Two days later try to control yourself, at church, when the same priest says that he is “bad at the Last Rites” because the recipients don’t actually die. Do not catch your sister’s eye, and definitely do not look at the woman the priest points to as proof; she is not your mother.

After church, race back to your mother’s bedside where your brothers have been keeping vigil. Lean in close and smile when she gestures toward your outfit and whispers, “I like this.”

Tell her you chose it with her in mind. Be so glad that “I’m hurting” won’t be the last thing she says to you.

Take turns with your father, sister and brothers, sitting with your mother and holding her hand. Notice when her tight grip, which you have had to peel off finger by finger, loosens, but don’t comment on it. Pass her hand gently to each family member in turn, like the baton in a terrible relay race.

Read to her and play music. Try not to flinch when the nurse nods approvingly and says, “Hearing is the last thing to go … well, nearly the last thing.” Wonder at how quickly you have become accustomed to your mother, your bright and opinionated mother, lying unconscious, mouth open and breathing heavily. Listen to her breathing and try to memorize the sound of it.

Three days before your mother’s death, start to sleep with the phone by your bedside. Be grateful on the two mornings you wake up without it having rung.

Sign up for the Well Newsletter

Get the best of Well, with the latest on health, fitness and nutrition, delivered to your inbox every week.

After: Hang up the phone and lean into your husband’s arms. Tell him, “Now I have to learn how to live in this world.”

Wake your siblings. Drive through the darkness to your father’s apartment. Continue to call it your parents’ apartment.

Write “RINGS” on a piece of paper and set it on the floor by your mother’s bed so that you don’t forget to ask the undertaker to remove two of her rings. Ask him to please leave her wedding band on.

Go funeral dress shopping with your sister. Buy the only dress you try on. Notice ruefully that you actually kind of like it. Too bad; you will never be able to wear it again.

Dig out the darkest sunglasses you own and wear them even on gray and rainy days.

Drink so much water. Grief is dehydrating.

Be thankful for friends who make very specific offers: to do your laundry; to pick up family members at the airport; to deliver breakfast; to buy you waterproof mascara.

Look around during the funeral and realize how many of your friends have also buried their mothers. Wonder if you were supportive enough to them, realize you couldn’t possibly have been, know that you will be from now on.

Pause, during the final verse of the final hymn, and listen with tears and joy while your sister and niece float the descant high above all the other voices.

Add your voice and hope that the music somehow reaches your mother.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!