— To start, you will probably be unprepared, no matter how much time you have to get everything in order

When my brother suggested that my father move in with him last year, it seemed like a no-brainer.

Dad was almost 91 then, and couldn’t really live alone any more. My husband and I (and our grouchy teenage son) lived near Dad, but we were feeling the strain of grocery runs and doctor appointments — and worrying about our son’s iffy high school grades.

If Dad moved in with my brother and sister-in-law, he’d have support and care; we’d be able to focus on getting our son from high school to college; and my brother would get a little extra income. A win-win-win!

So why didn’t things go as planned?

Hello, Blind Spots

Turns out that despite our best intentions (and you know what they say about good intentions), we were woefully unprepared — like many other well-meaning, middle-aged “kids” who take in a parent.

“Typically there’s no planning when an elderly parent moves in,” says Jennifer FitzPatrick, MSW, author of “Cruising Through Caregiving: Reducing the Stress of Caring for Your Loved One.”

“Despite our best intentions (and you know what they say about good intentions), we were woefully unprepared — like many other well-meaning, middle-aged ‘kids’ who take in a senior parent.”

That surprised me. If you’re in the middle of a health or financial crisis, as many families are when they take in an older parent, of course there’s no time to stop and think. But we had a few months to lay the groundwork for this transition — the timing, the cost, the logistics.

While those practical issues are important, many families experience a kind of caregiver shock because they underestimate the impact of the move on their personal time and space, their relationship with the parent/grandparent, and even the emotional dynamics within the immediate family itself. “A lot of people worry about the big things,” FitzPatrick says. “Like, what if Mom falls in the middle of the night? But it’s really the little things that build up.”

Given that multigenerational households in the U.S. are increasing, you’d think our collective ability to foresee some of these problems would also be expanding. But although over 50% of those living with adult relatives other than a partner or spouse say it’s convenient / rewarding all or most of the time, 23% say it’s stressful all or most of the time, and 40% say it is stressful some of the time, according to a 2021 survey by the Pew Research Center.

Surprise #1: Meet Your New Roomie

Why, exactly, is it so hard to adjust to the realities of shared living quarters with your aging mom or dad? Because . . . after decades of not living with your parent(s), FitzPatrick says, suddenly you’re roommates, with all the intimacies and frustrations that come with that arrangement. Like: Where do you put the used pull-up diapers? Is there a senior Diaper Genie? Should you just use a regular Diaper Genie?

Sorry to get right to the nitty-gritty, but these are the things that come up.

So, while rearranging the furniture and getting your parent to their physical therapy appointments is essential, also brace yourself for a string of minor irritations in the day-to-day that can really fry your nerves.

Surprise #2: Past Is Still Present

Making the roommate vibe worse is that your new roomie is actually your parent, and you’re not starting with a clean slate; you’re carrying some baggage. Whatever your traditional patterns are with your mom or dad, they don’t go away just because now they’re depending on you. As FitzPatrick put it: “The dynamics are so wonky.”

“Once your elderly loved one roommate moves in, everything gets magnified.”

Wonky is as good a word as any to describe how convoluted it feels like to deal with an aging parent who no longer calls the shots — yet they may think they do, or they may try to, or you may let them — or you may find yourself in a constant state of irritation and guilt because — wtf!

You know?

So while it’s tough to anticipate what the likely tension points might be, it’s not impossible. You just have to be honest with yourself — because once your elderly loved one roommate moves in, everything gets magnified. Being aware that these complicated feelings are naturally going to arise, in one way or another, can help you to spot them and — maybe — find more rational (or compassionate) ways to ease the situation.

Getting therapy is also a thought.

Surprise #3: Mind the (Expectation) Gap

When a senior parent moves in, one of the things you do to age-proof the house is to remove tripping hazards: slidey throw rugs, say, or your kid’s skateboard that lives in the foyer.

In the same way, you have to find a way to identify and articulate hazardous intra-family expectations so they don’t knock you sideways.

One of the biggest expectation gaps in families, FitzPatrick says, is around downtime. I thought she was going to flag money as a hotbed of miscommunication and crossed expectations. Because it is. But downtime can be even worse in a family caregiving situation because expectations can get muddled on so many levels.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

As my end nears, I crave the soul-to-soul connection of seeing friends in person

by Paul Woodruff

My good friends know that my end is near. Several of them have flown from far away to see me in Texas. They come for an hour or two of conversation, and then they fly home. That’s an expensive visit, and time-consuming for them. Why aren’t they satisfied to see me over the internet? I offer them that way out, but they insist on the trip. Why?

My friends tell me the internet is not a healthy place to develop friendships. I agree.

In my latest meeting with one friend, I gained a growing understanding of him at this stage in his life, and he of me, from subtle clues in our posture, expressions and body language — clues we could not have captured on the web. We kept close eye contact most of the time — something we could not have done on the internet. In the end, I felt that soul had touched soul.

Another recent visitor and I both changed as we came to know each other better. He told me he had shelved a beloved project to devote time to his business. We had little need for words after he told me of his decision. By contrast, the web would have allowed us hardly anything but words to go on.

Yet another friend told me that he had come to value in-person meetings because the business he had started was entirely in virtual space, and he saw its shortcomings every day. During his business meetings, he tells me, he suspects that many of his workers are multitasking — head and shoulders pretending to be paying attention, hands below camera range busy on other projects. They would not get away with that in person, he says. Because worries like this bother him every day, he sets a higher value than ever on seeing friends face to face. In-person encounters have become more intense for him, more special than they were before. Today, he wastes no time on small talk when we meet. We are each focused on the other.

I am not against the medium as such. I have taught on Zoom, and I know its strengths and weaknesses. I also understand that internet technology allows us to make and maintain connections that we would otherwise be denied. I know a stay-at-home parent with a large family who rejoices in her Zoom and Facebook connections. Without technology, she would be isolated, as parents were in the old days. Being physically together might be the gold standard for connecting, but we must not discount the value of other options. Whatever form of connection we are allowed is a gift.

But web-based connections are simply not as good as in-person ones. Technology tempts us into being satisfied with pseudo-friendships, and these can be dangerous. You’d be a fool to marry or promise sex to someone you had never met off-screen. That’s because the internet can’t reliably protect us from falsehood. Now, artificial intelligence has become a champion at falsehood. It can create false images of people — even of my friends — and get me to believe they are real.

Friends should be able to trust each other with secrets. Trust is at the heart of friendship, and trust can’t get started without privacy. The most valuable things friends say with each other must be safe behind a wall of “Don’t tell anyone else.” My wife and I need to process a rift in a colleague’s marriage to be clear about our own, but we don’t want the colleague to know what we are thinking. My wife and I are best friends, so I can trust her to keep our conversation private. But nothing has ever been private on the web. If I dare not tell you the truth of my heart, you cannot be my friend. But I don’t dare tell the truth of my heart to anyone I know through the internet. It follows that I cannot have friends through the internet.

I am delighted that my friends are flying in to see me from far away. They warm my soul. And having such good friends keeps me honest with myself and others. We do not come together to say goodbye. We come together to know each other better, right now, as we are at this hour, today. Each visit brings a growth of understanding in real time. I am very lucky to have such friends.

They are right to come in person. In actual presence, they can hold my hand, stroke my brow. At the end of my life, if they were trying to see me through the internet, they would fail. That dying thing will not be me. I am who I am through my actions, and dying is not an action. It is a happening. At the end, I will have no comfort in being observed. At the end, I cannot be seen. I want to be touched.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Green Burials

— The lowdown on natural interments and human composting

by Lou Fancher

With the Earth screaming for attention through increasingly severe natural disasters, people are realizing our planet is vulnerable. After centuries of believing this world is immune to the ravages of human exploitation, abuse and disregard, a new movement some refer to as “greening” has dawned. With its spread and growing sophistication, more people are acting in novel ways to restore and nurture the long-term health of the planet.

Recently, awareness that this gorgeous planet on which we live and on which we are dependent has spawned interest in green, natural or conservation burials, and human composting.

Often misunderstood to be one and the same, green—or “natural”—burials are closer to Indigenous and ancient burial practices in which bodies are returned to the earth or burned in funeral pyres with no toxic chemicals introduced into the soil or air, and using biodegradable containers. Conservation burials go a step further, with the model calling for cemeteries to operate under the stewardship of conservation organizations, such as land trusts, and comply with protocols that ensure no harm is done to the surrounding plant and wildlife ecosystems.

Human composting steps up to the highest level of “green” and involves a process that accelerates and abbreviates the up to 20 years required for a buried human body to decompose naturally. Through applied biological science, the conversion of human remains into soil, known as human composting or more technically as natural organic reduction (NOR), upends the conventional funeral industry’s environmentally destructive methods.

Bioneers, a nonprofit organization founded in 1990 in New Mexico by social entrepreneurs Kenny Ausubel and Nina Simons, maintains an active presence and leadership team in the Bay Area. The organization serves as a hub, offering workshops, community conversations, a full complement of social media productions that include radio, podcast and book series, a national conference and, through the local Bioneers Network, third-party media projects such as Leonardo DiCaprio’s movie, The 11th Hour, and Michael Pollan’s best-selling book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma.

This year’s Annual Bioneers Conference in April featured a robust roster of experts, keynote speakers and artists joined by thousands of civically active people on the UC Berkeley Campus and in venues across downtown Berkeley. Recognizing the commonality to all people of the death experience and with avid interest in “good deaths” along with preserving the planet’s longevity for future generations, the conference, Revolution from the Heart of Nature, included leaders in the areas of human composting, green burials and honoring the Earth as a final act.

Bioneers frequently gathers experts and composes panels who discuss specific, highly relevant-to-the-moment topics. The curated conversations hone general programs according to community interest and address anything from restorative food systems to youth leadership in the environmental movement to health care. Increased public awareness resulting from the programs sparks further discussions and activism, sometimes leading to solutions for eradicating obstacles to greater justice and equity, especially in marginalized communities.

“Contemporary culture has a hard time with death and dying,” says Bioneers President Teo Grossman. “This is true spiritually as well as practically, and it’s a conversation many would simply rather not have. As we know, there is literally no way around it. As we reckon with the impact humanity is having on the planet, exploring innovative approaches to death and dying should naturally be part of that conversation.”

Bioneers’ mission is to offer a public platform for people working on revolutionary solution-seeking projects who perhaps don’t have the bandwidth to do their own outreach to the press, Grossman says. While not claiming to be an expert, he says, “Our relationship with the natural world as humans, and our resulting actions, are clearly of significant importance. Innovative projects and ideas regarding practices around death and dying support extending that conversation to ‘new’ areas. I say ‘new’ in quotes because, as I’m sure the experts in this field have mentioned, the idea of integrating death and dying with nature and natural systems is probably as old as the idea of human rituals—and it’s only relatively recently that it has been dis-integrated.”

In light of Grossman’s earnest step back to remove himself from the limelight, it’s best to turn to one of the experts from the annual event to learn more about the green death movement and the level of interest in the Bay Area.

Katrina Spade, the founder and CEO of Recompose, a licensed, green funeral home based in Seattle, says there is strong interest in innovative death care and human composting specifically.

“This is not just people wanting to return to the Earth,” Spade said. “I love natural [green] burial, but if that’s all people wanted, it would be rising faster in popularity. Human composting lets you approach the whole thing in a way that feels new, even though nature is doing the work. The Recompose process is science coupled with an approach to death care that’s fresh, acknowledges death occurs and remembers that all of us have a capacity to be a part of the experience in a deeper way than might have been allowed by the conventional funeral industry.”

Recompose began accepting bodies for human composting in December 2020. In a nutshell, the process involves placing the body in an eight-foot-long steel cylinder filled with wood chips, alfalfa and straw. The mixture is calibrated for each individual and once the vessel is closed, the body’s transformation begins. During the next 30 days, the Recompose staff monitor the moisture, heat and pH levels inside the vessels, occasionally rotating them, until the body is transformed into soil. The soil is then transferred to curing bins, where it remains for two weeks before being tested for toxins and cleared for pickup. Eight-to-12 weeks after the process begins, the human soil can be used to enrich a garden, donated to a conservation organization to be used on privatized land or spread over multiple locations.

A composted body produces approximately one cubic yard of soil, an amount that fills a pickup truck bed and weighs upwards of 1,500 pounds. Importantly, and a reason many people are gravitating to NOR, is that the practice avoids conventional burial or cremation, which collectively adds one metric ton of carbon dioxide, per body, to the atmosphere. Additionally, the Recompose process does not use up valuable land or pollute the soil, and reduces contributions to climate change related to the production and transport of headstones, caskets, grave liners, urns and other items. It’s estimated the carbon output from a year’s worth of cremations in the United States is equivalent to burning 400 million pounds of coal.

“Some people say, ‘Composting humans has happened forever,’” Spade says. “But actually composting is a process that is by definition human-managed natural decomposition that is accelerated. Composting in any industry is something people are doing, not de-composting happening out in the wild. I think that’s a helpful distinction. Natural burial is just about a perfect solution for our dead, but because it takes land, it’s mostly a rural solution.”

She adds, “With composting, it’s possible to serve many more people in cities, because it doesn’t require the land of conventional burial or the time of natural burial that happens in the ground. Depending on soil quality and the climate, it takes years to decompose or desiccate a human body. With NOR, we’re transforming the human body inside of a highly managed vessel system—adding oxygen via a basic air pump and the exact recipe of plant materials that balance carbon and nitrogen so that the body will break down in a relatively short amount of time. We’re also monitoring for temperature because we want to make sure the material is safe for use on plants.”

The most common question Spade is asked about the process involves the bones. The mulch-like material at the end of the first 30 days still has bones, along with any non-organic matter, such as a titanium hip. The bones are reduced, basically pulverized as they are in a cremation, and turned into a sand-like substance. Inorganic materials are recycled, if possible. Once all the microbial activity is complete and the soil dries out, she says the remains scientifically, biologically and by look and feel, resemble compost a person might buy at a nursery.

Lynette Pang is a Bay Area resident, passionate gardener and an early investor in Recompose. After more than 20 years working in the investment management industry, she decided the second half of her life would involve something revolutionary. She began reading books on death, dying and grief, including From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death, by Caitlin Doughty.

“The book is a treasure,” Pang says. “But one chapter stood out: it was about something called the Urban Death Project. Wanting to learn more, I turned to the internet and learned about Recompose, formerly called the Urban Death Project. The concept of human composting was right up my alley. It just makes sense. I truly believe the practice of human composting will change, and maybe even save, the world. It is an investment in hope.”

Pang says she plans to participate in Recompose and hopes taboos surrounding death will diminish and that people will speak freely about how they want to die. “We are born, we live and then we die,” she says. “To me, it’s just that. When it is time to make my exit, whether that is tomorrow or many, many years from now, I shall be gifted to the earth as glorious, black gold.”

To do so, at least until 2027, Pang and other Californians will have to travel to Seattle.

“California is a great example of what’s holding NOR back,” Spade says. “The regulatory law passed in 2022 authorized NOR, but then there was a four-year regulatory period tacked on. How could it take four years to write regulations around NOR? Washington [state] was first to legalize the process, and we have two agencies that wrote regulations that are straightforward and make everything safe. Washington passed the bill in May 2019 and it went into effect May 2020. We did it first and had to do it from scratch, but other states could look to Washington [to write their regulations].”

She points out it takes a fair amount of capital to get a facility up and running, and adds that “any type of funeral care isn’t something you can snap your fingers and have up and running instantly.” In the meantime, Spade dreams and plans to open and direct facilities similar to Recompose’s Seattle home base in the top 12 urban centers in the United States. Conversations to franchise the brand and system to funeral homes and cemeteries have begun as the leadership team structures licensing agreements.

Spade recounts a favorite client story. “It’s about a person named Wayne who died and his sister brought his remains home to where he gardened his whole life. His neighbors and friends came with five-gallon buckets and took some of him home to their own gardens.” Spade says half of the families bring a truck or trailer, pick up the soil and take it home; the other 50% choose to donate it, through Recompose, to conservation efforts. “We have land partners that are conservation trusts owned by nonprofits,” she says. “Clients can donate soil to that trust so it is used in the forest to nourish the land. Families can go visit those places.”

A more universal story is the number of people who learn about human composting and green burials and say, “I want that.”

“As I began to grow Recompose, it became clear again and again that there was a lot of interest out there for options in funeral care that are sustainable and aligned with the planet,” Spade says. “Having your last gesture be a good one on the Earth, they say, is important.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

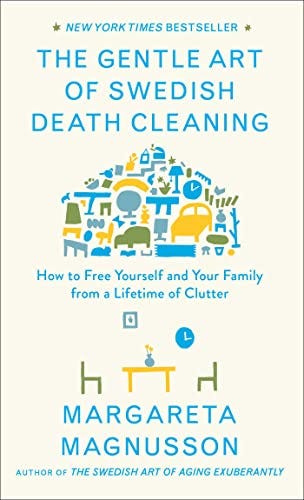

What Is Swedish Death Cleaning?

— How the Method Can Help You Declutter

There’s no shortage of home decluttering methods — take Marie Kondo’s popular minimalist approach, the KonMari Method, for example. But when it comes to downsizing your belongings, including furniture, clothing, shoes, kitchen essentials and even documents, to prepare for your older years, Swedish death cleaning is an approach that’s worth considering.

Swedish death cleaning is a well-known concept in Swedish and Scandinavian culture, where you work on eliminating unnecessary items from your home, so loved ones won’t be burdened with the task after you pass.

The thorough organizing method involves editing everything from furniture and clothing to the ever-growing piles of documents that’s been difficult to control over time. It’s a slow process that’s been all the rage lately, thanks to Peacock’s new show, The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning, which is produced by Amy Poehler. While Swedish death cleaning is all about holding onto essential belongings, pinpointing the items you want to keep and part ways with isn’t an easy process.

So, follow the checklist below to get started and decide whether this buzzy cleaning method is right for you.

Swedish death cleaning checklist and steps

In 2017, Swedish author Margareta Magnusson coined the term in her New York Times best-selling book, The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter. In her guide, she urges those 65 and up to partake in the task, though it never hurts to begin earlier, especially since decluttering is a great stress reliever.

When starting, focus on areas you may find the easiest to tackle. According to Magnusson’s book, the attic or basement may be best since they are more likely to have unnecessary excess items, like broken seasonal decorations. Choose belongings you don’t have emotional attachments to and determine the category you want to scrap first, such as unwanted clothes, books or even half-empty bottles of skincare. There’s actually no time limit or definitive checklist to know when you’re done. It’s all about how you feel and the goals you want accomplished.

The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning

1. Start with your closet.

There’s no need to start with personal and sentimental items, like love letters or your children’s photographs. In fact, our closets and drawers may be the easiest to organize. You’re sure to have two or more garments of the same color and size that you never wear.

Choose clothes that no longer fit, discard damaged shirts or pants and donate items that no longer suit your lifestyle. Since you may have a bulk of clothes to sort through, don’t worry about how long it’ll take. Start with seasonal clothing and gradually work your way through your piles over the course of a few months (or even years if you must!).

2. Declutter by size.

Go for the large items first, such as any furniture or rundown decor hidden away in the garage —think broken tables, chairs or smelly rugs. Then, move on to smaller items you can easily discard in boxes. We’re talking about shoes you barely wear, any excess magazines and more!

If you find it easier, go room by room instead of decluttering your house as a whole. You can start off in the kitchen by ridding your cabinets of the 20 plates hidden in the back or burnt pots you still keep in the oven. As you clean, you may find many “just in case” items you’ve been holding onto for emergencies. Sadly, they only create clutter and should be discarded too.

3. Start buying less.

The fewer items you have, the less time you’ll need to clean! It doesn’t matter what age you start Swedish death cleaning, it pays to limit shopping to avoid feeling overwhelmed. And don’t worry, as this doesn’t mean you have to stop buying the things you love. It’s simply about taking time to rethink your purchases— for example, there’s no need to buy yet another pair of shoes when you already have a large sneaker collection.

4. Discuss the process with loved ones.

Your family and friends may not understand why you want to start this process, but it’s still important to share the journey with them. Plus, they may have items they want to keep or pieces they want you to cherish until the end (a school painting or Christmas gift are just a few ideas to consider). It might also be helpful to invite them on your decluttering journey. It can be a beautiful and nostalgic way to reflect on memories throughout your life.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Finding gratefulness in the grief

— “How are you?” kind people ask. “How am I?”, I ask myself. It’s a tough one. I’m ok. And sometimes I am not.

I allow a few tears each day. I am still grieving the death of my beloved dad. There are moments when I am blindsided by grief, moments when I cry in the car on the phone to my mum; grieving for her loss, grieving for our loss. I still can’t quite believe I will never see him again. As this season changes, as his last season on earth comes to an end, I feel sad.

They don’t tell you that grief is a physical sensation. I can feel the weight of it as I carry it with me each day. It builds over time and a big cry usually resets me. Sometimes a cry won’t do though, and the grief catches me off guard and slams into me – like a hard whack in the chest. It can literally take my breath away. Each day, I shuffle around the hole dad has left in the world, but on these occasions, I fall in.

There is another sensation too though. And this is the bit I struggle to write about. The last few months have seen me happier than I have been in some time. In years perhaps. I think this happiness stems from gratefulness. Having witnessed dad’s bravery, and his suffering, having seen the edge that we are all teetering so close to; I now, quite suddenly, understand everything differently.

I feel so lucky to have had him. But more than that, everything feels touched by this new gratefulness. I feel so lucky to have a job that I love. I feel so lucky to be needed in the middle of the night by little chubby hands.

The things that used to cause anguish – like being woken at 5am – I now understand slightly differently. Now don’t get me wrong, I still curse under my breath when I hear the early morning wail and have to haul myself from the warm duvet. But it’s followed by new sensations and thoughts. I get to see the sunrise. I bring Freddie to a local cafe that opens at 7am, but that lets us in early. I play beautiful music in the car on the way there, I sing to my gorgeous boy as he laughs and claps. I get to drink hot coffee with lovely early-rising strangers. They coo over Freddie and we chat about our lives in the half-light. They are gentle and kind women, so comforting and warm.

The thing is now, quite literally, no one is dying. For the last six months of my life, the person I loved the most WAS dying. There was nothing I could do to stop it, there was no way to ease his suffering. The pain in that was overwhelming – daily, hourly. It was a dark cloud, a black ink, that covered everything, that seeped into every moment. It was all we could see. And now it’s gone, now he’s gone, it’s like taking a blindfold off. The light is painful sometimes, sometimes it’s too much and I need to take a moment to close my eyes and remember him. But when I open them again, I am so grateful to see the sky. Of course, there is still pain, there is still loss, I still hurt, we still cry. But I know that he is no longer suffering. That wherever he is, there is no pain.

I hope that I don’t sound holier than thou, I won’t be moving to the mountains and buying an orange robe anytime soon. Life still has all its usual ups and downs. But dad’s death, and all the shitty events that came before in quick succession (a miscarriage, the death of my grandad, a pandemic, and my mum suffering from long Covid) have all given me something. I am grateful for them. This one fragile and precious life.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What Happens to Patients After Taking End of Life Drug

Many people might not like talking about end-of-life care or death until they’re faced with it themselves, but this hospice nurse wants to remove the taboo from the topic and educate people instead.

As an intensive care unit (ICU) nurse for over a decade, Julie McFadden, 40, focused on keeping patients alive, but when she made the switch to hospice care eight years ago, her attention turned towards making people feel comfortable as they neared the end.

McFadden, from California, regularly talks about the realities of hospice care, and what happens when a patient opts for medical aid while dying, on social media. She told Newsweek: “My main point is to make everyone a little less afraid of death. I want to change the way we look at death and dying.”

Medical aid in dying (also referred to as death with dignity, physician-assisted death, and aid in dying) is the prescribing of life-ending medication to terminally ill adults with less than six months to live, who are mentally and physically capable of ingesting the medication independently.

At present, only 10 states and the District of Columbia permit this process, but there is growing support elsewhere. A survey of over 1,000 people in 2023 by Susquehanna Polling and Research concluded that 79 percent of people with a disability agree that medical aid in dying should be legal for terminally ill adults who wish to die peacefully.

States where it’s permitted include Colorado, California, Washington, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, Oregon, and Vermont. Legislation is also being considered in Massachusetts, New York and Pennsylvania.

How the End of Life Drug Is Administered

As a hospice nurse in California, where a bill was passed to permit death with dignity in 2015, and became effective from June 2016, McFadden has assisted many patients who wanted to die on their terms.

She believes that there is real beauty in someone being able to have full autonomy over their death and choosing when they go, but she knows it’s a polarizing issue.

“People have to remember that not everyone has the same beliefs and I think it’s a beautiful thing that someone gets to have control over,” McFadden told Newsweek. “It’s powerful to witness someone be so alert, say goodbye to their loved ones, have their loved ones watch them take this drink and then die, but still be willing to be there to support them.

“I think most people in the U.S. have no idea that this law even exists, and even when I give very descriptive explanations of what the law is, what it means, what the criteria is, there’s still people who think I’m just overdosing patients with morphine.”

In order to acquire the medication, an individual’s request must be approved by two doctors, they have to undergo a psychological evaluation to ensure they aren’t suicidal, and doctors have to confirm that the person is capable of making their own decisions. Patients with certain conditions do not qualify, including those with dementia.

If approved, the person must take the medication themselves, and they can have family, friends, and hospice staff present if they wish.

Since June 2016, in California 3,766 death with dignity prescriptions have been written, and 2,422 deaths registered. To protect the confidentiality of any individual who makes this decision, death certificates usually note an underlying illness as the cause of death.

McFadden continued: “There are a few drugs mixed in, it’s taken all at once and the initial drugs kick in very quickly, within three to seven minutes. This person who ingested this drug will fall asleep or basically go unconscious. I say fall asleep just so people can picture what it looks like, but they’re unconscious.

“Then, the body is digesting and taking in the rest of the drugs that are also in that mixture, which will eventually stop the heart. It’s a general sedative and then they take two different cardiac drugs to stop the heart.

“They have a change in skin color and changes to their breathing, in what we call the actively dying phase, which is the last phase of life.”

People Have A Lot of Misconceptions

Regardless of whether you’re in a state that permits physician-assisted death or not, dying isn’t regularly talked about in a positive way.

One of the reasons why McFadden wants to have a more open conversation about it is to remove any prior misconceptions that people might have and educate them on what really happens.

“I have not seen anyone show signs of pain, but people are always concerned about that,” she said. “In general, if you’ve done this for a long time, if you’ve been in the healthcare system and work as a nurse or by someone’s bedside, you know what a body in pain looks like, it’s very obvious.

“A person who is unconscious and can’t verbally say they’re in pain will show you with their body language. Most people that have taken this medication who I have witnessed did not show those signs. I witness it day in, day out, but it’s pretty miraculous to see how our bodies, without even trying, know how to die. They’re built to do it.

“People get really angry and think I’m trying to hurt people. I always want to educate people around this topic, because the main thing people don’t want is for their loved ones to suffer at the end of life.”

As an ICU nurse formerly, McFadden explained to Newsweek that she was trained to keep patients alive, and they “didn’t have conversations about death early enough.” Despite patients being near death, they were kept alive through machinery for weeks or months, before ultimately dying on the ward.

Many of the country’s biggest medical associations are conflicted by death with dignity, with some choosing to endorse it, and others speaking against it. The American Public Health Association, and the American Medical Student Association are among the bodies to endorse it, but it has been publicly opposed by the American Medical Association and the American College of Physicians.

Talking Openly About Death

In 2021, McFadden set up her TikTok account (@hospicenursejulie) to speak openly with her followers about death and answer any questions people might have. Many of her videos have gone viral with millions of views, and while she does get a lot of positive feedback, there is also plenty of negativity.

There are people who wholly disagree with her advocacy for death with dignity as they claim she is playing God, or that she’s promoting suicide. But by having an open conversation, the 40-year-old hopes to make people less fearful of dying.

Speaking to Newsweek, she said: “Most of my audience is general public, that’s why I don’t talk like I’m speaking to other nurses or physicians. I talk like I’m speaking to my families who I talk to in everyday life. I think death just isn’t talked about, or it’s not explained well.

“I’m seeing so many times that people who are willing to have difficult conversations about their own death, who are willing to say they’re afraid to die, those patients who were willing to ask me those things and talk to me about death, had a much more peaceful death.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Care of the Body After Death

By Glen R. Horst MDiv, DMin, BA

Family members or close friends may choose to be involved in washing and dressing the body after death has occurred. Caring for a body is not easy and can stir up strong emotions. See Moments After a Death. Many people turn to health care providers and funeral directors for help. They find comfort and assurance in entrusting the body to those who provide professional services. The deceased may have left instructions for their after-death care to be handled by the health care team and chosen funeral home. Other people practice religions or belong to communities that view care of the body as a family responsibility. Their faith community, elders or neighbours provide guidance and support for hands-on care of the body. For some, this is a way of honouring the person – a final act of kindness to him or her.

This article outlines the steps involved in the care of the body after death.

In advance of the death

Talk to the health care team in advance about family or friend involvement in after-death care. You may also want to talk to the health care team about the supplies and assistance that will be required.

Washing, dressing and positioning the body

Washing and dressing the body is an act of intimacy and sign of respect. Those who were most involved in the person’s physical care may feel the most comfortable in doing this. Continued respect for the person’s modesty is essential.

Regardless of whether the person died at home or in hospital, hospice or nursing home, washing and positioning the body is best done where death occurs before stiffening of the body (rigor mortis) sets in. Rigor mortis happens within two to seven hours after death. Regardless of the location of care, you may need four to six people to help in gently moving and turning the body.

At home, you can wash the body in a regular bed. However, a hospital bed or narrow table will make the task easier. Since the body may release fluids or waste after death, place absorbent pads or towels under it. It is important to take precautions to protect yourself from contact with the person’s blood and body fluids. While you are moving, repositioning and washing the body, wear disposable gloves and wash your hands thoroughly after care.

Washing the person’s body after death is much like giving the person a bath during his or her illness.

1. Wash the person’s face, gently closing the eyes before beginning, using the soft pad of your fingertip. If you close them and hold them closed for a few minutes following death, they may stay closed on their own. If they do not, close again and place a soft smooth cloth over them. Then place a small soft weight to keep the eyes in position. To make a weight, fill a small plastic bag with dry uncooked rice, lentils, small beans or seeds.

After you have washed the face, close the mouth before the body starts to stiffen. If the mouth will not stay shut, place a rolled-up towel or washcloth under the chin. If this does not provide enough support to keep the mouth closed, use a light-weight, smooth fabric scarf. Place the middle of the scarf at the top of the head, wrapping each end around the side of the face, under the chin and up to the top of the head where it can be gently tied. These supports will become unnecessary in a few hours and can be removed.

2. Wash the hair unless it has been washed recently. For a man, you might shave his face if that would be his normal practice. You can find step-by-step instructions in the video Personal Hygiene – Caring for hair.

3. Clean the teeth and mouth. Do not remove dentures because you may have difficulty replacing them as the body stiffens.

4. Clean the body using a facecloth with water and a small amount of soap. Begin with the arms and legs and then move to the front and back of the trunk. You may need someone to help you roll the person to each side to wash the back. If you wish, you can add fragrant oil or flower petals to your rinse water. Dry the part of the body you are working on before moving to another. Some families or cultures may also choose to apply a special lotion, oil or fragrance to the person’s skin.

5. Dress or cover the body according to personal wishes or cultural practices. A shirt or a dress can be cut up the middle of the back from the bottom to just below but not through the neckline or collar. Place the arms into the sleeves first and then slipping the neck opening over the head, tucking the sides under the body on each side.

6. Position the arms alongside his or her body and be sure the legs are straight. If the person is in a hospital bed with the head raised, lower the head of the bed to the flat position.

The Canadian Integrative Network for Death Education and Alternatives (CINDEA) has a video series on post-death care at home that includes videos on “Washing the Head, Face, and Mouth”, “Washing the Body”, “Dressing the Body”.

Next steps

If a funeral home is assisting with the funeral, cremation or burial, call to arrange for transport of the body to their facility. If the death has occurred in a hospital, hospice or long-term care facility, the staff will arrange for the body to be picked up by the funeral home of your choice. In hospital, once the family agrees, the body is moved to the morgue and kept there until transported to the funeral home.

If your family is planning a home funeral or burial, cover the body in light clothing so it will stay as cool as possible. A fan, air conditioning, dry ice or an open window in the room where you place the body will help to preserve it.

See also: Planning a Home Funeral

For more information about providing care when death is near or after a death, see Module 8 and Module 9 of the Caregiver Series.

For additional resources and tools to support you in your caregiving role visit CaregiversCAN.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!