At 90, a grieving widower read an essay from medical ethicist Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel and realized he’s grateful for all his years, even in the face of sadness

Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, an oncologist, medical ethicist and adviser on health care to President Obama, decided he wanted to die when he became 75 years old. He announced his intention in an essay in The Atlantic Monthly when he was 57. Emanuel saw only decline after 75, when the heights to which he had ascended would pitch downward.

As a father, he would have already celebrated the college graduations and career choices of his children, their marriages and the birth and growing independence of his grandchildren. It would be time, he felt, to abdicate the role of patriarch, stepping aside so his children could climb their own mountains.

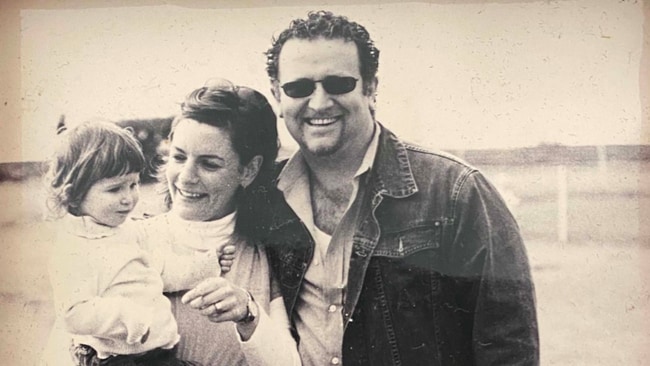

When Muriel died suddenly and unexpectedly, grief mounted my back and drove me into despair’s black waters.

As a physician, concern that declining dexterity, reading of medical advances but not leading them, being a patient rather than treating patients and taking medication he previously prescribed, only hardened his resolve. He would die up there on the mountain, not laced to a catheter in a nursing home down in the valley. Emanuel is now 65, and nothing he’s written since that I’ve read indicates he’s changed his mind.

Finding A Way to Live

Shortly after my wife died in the early days of the pandemic, a friend sent me Emanuel’s essay. I had already lived 15 years beyond my own 75th birthday and was thankful I hadn’t read the article in the first agonizing months of my loss. For Emanuel, 76 years would have been one too many to live. Would his words have tempted me to think a day without Muriel was one too many to endure?

When Muriel died suddenly and unexpectedly, grief mounted my back and drove me into despair’s black waters. Had I already read Emanuel’s essay, I might have stroked deeper, hoping to drown. But I hadn’t read it and imagined the arms of my children thrashing the dark water, hoping to grasp my hand and pull me to the surface. My death, so soon after their mother’s, would have devastated the family Muriel and I had built. I would have to find a way to live even if I wanted to die.

Since I was 22, just off a troop ship from Korea, I turned to Muriel in moments of uncertainty. I was now 90 and doubted I had the resources and will to go on without her. Emanuel — a physician and medical adviser to a president — saw no point in living beyond age 75. What reason did I have to leave my empty bed to go to other empty places? If there were reasons to live, I would have to reach deep within myself to find them.

The few reasons I did find seemed to have no purpose, certainly nothing important enough to live for. Yes, I speak every day with my children and each weekend with my grandchildren. But the emptiness within me left me with little to give them. I understood that if I found no reason to go on, the despair I felt could kill me. That would take time when every clock seemed stopped at midnight. But, unexpectedly, time’s slow crawl proved to be a blessing: it gave me hours to think of nothing but what made life worth living.

Gradually, in those midnight hours, flickers of light began piercing the darkness. A friend called and said “I don’t like the sound of your voice. I’m coming over. Meet me outside and let’s talk.” It was the first of the acts of kindness that carried with them a hint that I could heal.

A Buddhist friend urged me to talk with Muriel. “She’s not gone,” he said. “She’s in your being. Talk with her!” I was about to shrug off his advice but was in such pain I would try anything.

Understanding Life’s Purpose in My Nineties

Just thinking of Muriel began to fill the empty places within me. I called out to her, hoping she would hear my voice and that I would hear hers. Her first words sounded so like her. She told me it wasn’t what I lost that mattered. What mattered was what we had for all those years. Her words, as they always had, brought with them the gradual return of my courage.

I am certain I have found reason to press deeper into my nineties.

Now, three years since I lost Muriel, I realize what kept me from drowning in those dark waters. I was startled to find how unimportant many of my relationships and activities had been. If I were shaken awake in the middle of the night and asked what kept me alive, I could think of only two reasons. It was being surrounded by the love of my family and by acts of kindness from friends, sometimes from strangers. It was these that gave me the strength to go on, not dinners with people I barely knew.

I understood my life would have purpose only if I touched others with acts of kindness and brought love to every encounter with my family and close friends.

I need no reminder that I’m one of the “old-old.” The slightest graze leaves an angry welt; a scratch I barely feel bleeds through multiple band-aids.

But I am certain I have found reason to press deeper into my nineties. My children and grandchildren will have to climb their own mountains, but I believe they’ve seen that mountains can be climbed even when bearing the heaviest of burdens.

Perhaps that’s reason enough to be grateful I’ve remained alive in the years Dr. Emanuel has chosen to forego.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23907760/April.jpg)