John started his first appointment in the Neuropalliative Care Clinic with, “I want to talk about MAID.” In our clinic, his request for medical assistance in dying is common. As legislated by government, I referred him to the MAID navigator. I had one request: that John wait to make his MAID decision until after seeing a community palliative care physician.

At his next appointment, John informed us he had withdrawn his MAID request because his primary symptom —pain — was now well controlled after our suggestions and those of the community palliative care doctor. John lived for two more years, during which he became closer with his daughter and continued to enjoy the company of his siblings.

John is not unusual. Neurologic illness accounts for 18 per cent of deaths in the Canada but rarely has palliative care involvement. By contrast, cancer accounts for 20 to 30 per cent of deaths, but typically receives 75 per cent of palliative care.

Part of the challenge is that palliative care services are often hospital-based, but most people who could benefit get their care in the community. Similarly, patients have recently refused palliative care in the belief that is the same as MAID. In 2017, MAID accounted for 1.07 per cent of deaths in Canada, increasing to two per cent in 2019.

In June 2016, the passed legislation that gave all eligible Canadians the right to request MAID. Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons required physicians to refer people who request MAID to services or arrange for a physician who would make the referral.

Since then, every province and territory devoted resources to navigate requests and assessments for MAID. Typically, provinces have a website for self-referral, easily found by internet search and/or dedicated health-care staff to help navigate the MAID process or inform those who are MAID-curious.

Complicated referrals

By contrast, the referral process for palliative care is often convoluted. Many provincial web pages simply give a definition of palliative care (some confuse the issue by including the MAID navigation site) but do not provide a central access point for physicians or nurses. Referral forms (where available) are complex, which creates another barrier to access. Many palliative care programs have an unofficial prognosis of three to six months’ life expectancy for services, despite research demonstrating that early palliative care improves outcomes and in fact, can prolong life.

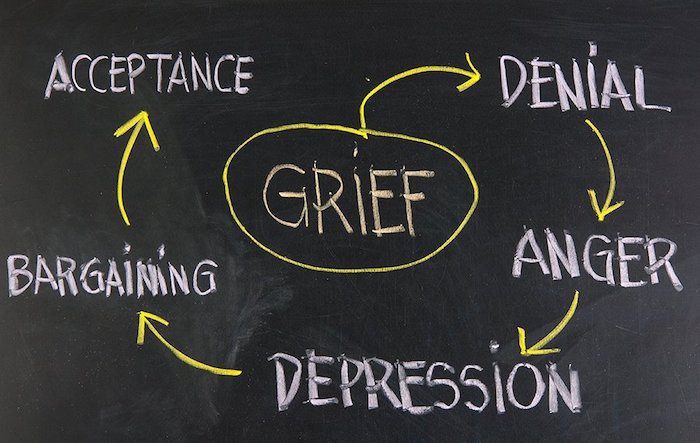

What is the disconnect? Health-care providers are an unexpected barrier as they often cling to the belief that palliative care is for the imminently dying or means to give up hope. For the public, palliative care means dying soon.

But modern palliative care is about living well now, meeting patients’ goals and finding meaning in life. For John, we helped him set goals, focused on the positive in his life, like his better relationships with his children and ongoing closeness with his siblings. His sharp sense of humour emerged despite communication challenges.

Additionally, many palliative care programs exist in the oncology (cancer) department and thus, their focus is cancer-based. Twenty per cent of people die from cancer, but receive 75 per cent of palliative care services. Current training for palliative care physicians requires exposure to other patient populations like heart failure, kidney failure and neurologic illnesses, but health-care systems are slow to change.

And finally, the workforce for palliative care is inadequate to meet the needs for Canadians with chronic burdensome illnesses.

Making palliative care more accessible

The solution requires a multi-faceted approach. All health-care providers need to have general palliative care skills because, in the way we all learn to control blood pressure and read a basic electrocardiogram, palliative care is part of good medical care.

At a systems level, placing as much importance on palliative care as we do on MAID might make navigation to palliative care less difficult for patients and clinicians. Given the broader applicability of palliative care, it is time for palliative care to become an independent department. Up to 28 per cent of Canadians will be seniors, which means more people with multiple, chronic conditions that could benefit from a palliative approach.

Building the palliative care workforce is essential. The palliative care workforce in Canada is estimated to be 773 doctors for a population of 39 million. Once the palliative care workforce is established, educating the public that palliative care includes a holistic approach to wellness and meaning in life can help re-frame and increase acceptance.

There are more people like John who should connect with a palliative care team before walking down the road to MAID. Let palliative care help you live well, now.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!