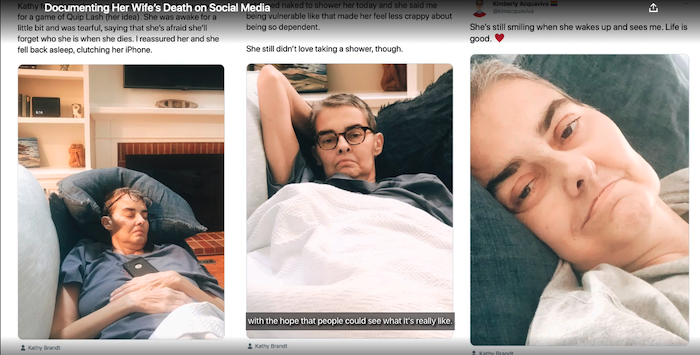

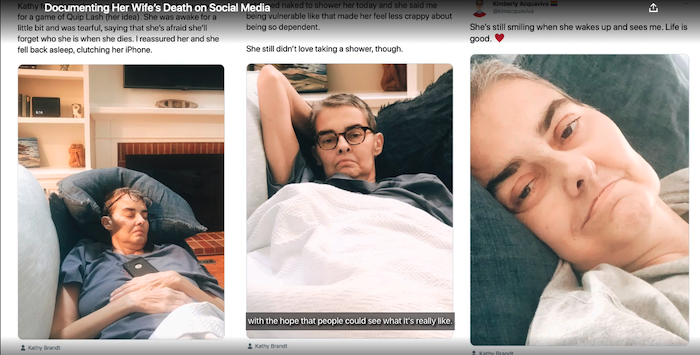

In “Documenting Death,” a couple who work in palliative care take to social media to share their experiences after one of them receives a terminal diagnosis.

Complete Article And Video ↪HERE↩!

The Amateur's Guide To Death & Dying

Enhancing Life Near Death

Complete Article And Video ↪HERE↩!

We’ve surpassed 600,000 COVID-related deaths in the United States, and many people are grieving a loss related to this pandemic.

Whether you’re dealing with a pandemic-related loss or grieving a loss related to something else, finding a way to cope is critical.

Grief counseling may help people of all ages process and cope with their feelings after experiencing a loss.

In this article, we look at how grief can affect you, the stages of grief, and how therapy for grief can help.

Therapy for grief, or grief counseling as it is often called, is designed to help you process and cope with a loss — whether that loss is a friend, family member, pet, or other life circumstance.

Grief affects everyone differently. It also affects people at different times. During the grieving process, you may experience sadness, anger, confusion, or even relief. It’s also common to feel regret, guilt, and show signs of depression.

A licensed therapist, psychologist, counselor, or psychiatrist can provide therapy for grief. Seeing a mental health expert for grief and loss can help you process the feelings you’re experiencing and learn new ways to cope — all in a safe space.

Grief generally follows stages or periods that involve different feelings and experiences. To help make sense of this process, some experts use the stages of grief.

The Kübler-Ross stages of grief model, created by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, was originally written about people dying, not about people grieving, but later, she wrote on applying the principles to the grieving process after a loss.

There are five stages of grief under the Kübler-Ross model. These include:

Over the years, some experts expanded this model to include seven stages:

It’s important to note that the empirical evidence to support the stages of grief as a model is lacking, and, according to a 2017 review, some experts believe it may not be best when helping people going through bereavement.

Kübler-Ross’s model was, after all, written to explore the stages that people who are dying and their families go through, not for people to use after death.

One positive outcome of this model is that it emphasizes that grief has many dimensions, and it’s perfectly normal to experience grief through many feelings and emotions.

When grief is long lasting and interferes with daily life, it may be a condition known as prolonged grief disorder. According to the American Psychological Association, prolonged grief is marked by the following symptoms:

In general, this type of grief often involves the loss of a child or partner. It can also be the result of a sudden or violent death.

According to a 2017 meta-analysis, prolonged grief disorder may affect as many as 10 percent of people who have lost a loved one.

Seeking therapy after a loss can help you overcome anxiety and depression by processing your experience at your own pace.

Each mental health expert may utilize a different approach to help patients tackle grief, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) are two methods often used for bereavement.

CBT is a common treatment approach for mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

During a CBT session, the therapist will help you identify negative thought patterns that can affect your behaviors.

They may ask you to explore thoughts related to grief and loss or other unhelpful thoughts to address how these thoughts affect your mood and behavior. They can help you lessen the impact with strategies such as reframing, reinterpreting, and targeting behaviors.

ACT is another method that may help with grief and loss.

According to a 2016 research paper sponsored by the American Counseling Association, ACT may also be helpful with prolonged, complicated grief by encouraging clients to use mindfulness to accept their experience.

ACT uses the following six core processes for grief counseling:

Grief counseling for children incorporates many of the same elements as counseling for adults, but the therapist works in ways that are appropriate for children.

According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, children, especially younger ones, react differently to death than adults.

In general, preschool-age children see death as temporary and reversible, but kids ages 5 through 9 think slightly more like adults. Some common ways grief counselors treat children include through:

Self-care is a critical component of the grieving process. In addition to participating in therapy, consider things you can do to take care of yourself. Here are some ideas to get you started:

It can be difficult to quantify or predict the outlook for people dealing with grief, especially since each person manages it in their own way. It’s also challenging to predict if any one treatment may work the best.

Grief does not follow one particular path. Healing is unique to each individual, and the outlook for people dealing with grief looks different for each person.

A therapist can play a key role in supporting the healing process by facilitating counseling sessions based on your situation.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

By Adam Mansbach

We have just lived through a year that burned ritual to the ground — both the rituals of life and the rituals of death. All of us who have lost someone have had to contend with the partial or total suspension of the comforts to which we might have looked. We are not able to cry together, nor crowd a house with food and bodies. Perhaps we have been denied even the chance to bear witness to the jolting finality of burial. And so we may find that our grief cannot run its course — that it is unable to find its way back to the ocean, absent the normal waterways.

Ten years ago, when I lost my brother David, I did not know how to grieve. Not because I lacked experience, but because suicide obliterates the rituals we have built around death. How do you celebrate a life when the person who lived it contends, as David did in the note he left behind, that he had always wanted to be dead? How do you mourn when the death has been fought for — sought, with the same fervor that most of us seek to continue living?

When I try to talk about it, suicide defies me. I have learned that it cannot be grafted onto other conversations. Even discussions of death, of depression, provide not a means of ingress but a reminder that there are no bridges to this island. You must swim. The few times I have done so, I have been a little drunk, and hours into a first conversation with someone I know I want to keep. A sense that I am being dishonest takes hold of me — that everything is false until I bare this wound. I grow impatient to find a way, bore open a point of entry, my heart throwing off sparks as if I were working up the courage to declare my love.

But once I speak it, I must contend with what it feels like to recite a narrative I have whittled down from something incomprehensible to a set of talking points. It feels obscurely disrespectful, to speak as if I understand. My brother bought an expensive skateboard that did not arrive on his doorstep until after he was gone; he was planning to live and planning to die at the same time. It was not an either/or but a both at once — no more a paradox than a train station with two sets of tracks running in opposite directions. I can write these words, shape this idea into a metaphor, but I don’t truly understand it at all.

I wish I could say that I learned to be gentle with myself when I lost David and realized that I had no means of finding peace. But I was not. I tried to force myself, at every turn — to cry when I couldn’t but felt I should, to let go of what I didn’t actually want to relinquish, to hold onto things that burned. I tried to write about him almost immediately, and castigated myself when no words came.

It took me nine years to find the language I was looking for — not a language that alleviated my grief, but one that contained it. It came suddenly, the way they say grace does. The week David would have turned 40, I began to write very fast, with an intuition about what came next and how disparate ideas connected that I trusted entirely — even or perhaps especially when it meant I was putting forth a notion only to question or disavow or undercut it.

I knew it was a ritual, even if I did not know whether a ritual was meant to fill the hole left by the loss, or deepen it until I could crawl out the other side. I would not say I found closure, as some people have asked. That word is loaded and mysterious to me. But I did find something, or perhaps something found me.

It was David’s story; it was my own. I could not tell it until his death had receded enough for me to see the whole thing at once, and until I realized that it was OK, was necessary, for the particles of my loss to float in solution, unreconciled, suspended like judgment. That if all I did was stare at them the way I might the tank of undulating jellyfish at the aquarium — which I also cannot understand, but do not seek to — that would be enough.

I think about this now, at a time when so many of the rituals that have guided and succored us are trapped on the other side of the glass. What can we do, when what we need cannot be accessed, or simply does not exist? Perhaps we can trust ourselves to intuit and then invent the things we need — to become the rituals that will sustain us.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

By Shelby Hartman & Madison Margolin

Erinn Baldeschwiler had already been having a rough go of it. A mother of two teens, she was going through a divorce, moving out of her house, and splitting from her business partner all as the severity of the Covid-19 pandemic was becoming a reality. Amid it all, she was diagnosed with stage four, triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. The doctors told her that even with chemotherapy every week — something which she knew would severely impact her quality of life — and immunotherapy every two weeks, she likely had about two years to live.

“It was devastating,” says Baldeschwiler, 49. “I thought, what if I’m not going to be here for my kids? A dear friend passed very suddenly, unexpectedly from cancer a few years back and I just know the pain that it leaves behind. It was really, really heavy.”

Now Baldeschwiler, along with Michal Bloom, another cancer patient diagnosed with stage 3 ovarian cancer in 2017, their palliative care physician, Dr. Sunil Aggarwal, and his clinic, AIMS Institute, are suing the Department of Justice and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Baldeschwiler and Bloom want to try psilocybin, the psychoactive component in psychedelic mushrooms, in a therapeutic context for what’s sometimes called “end-of-life distress,” depression, anxiety, and other mental health challenges that can come along with a terminal diagnosis.

Kathryn Tucker, one of seven attorneys on the case, says Baldeschwiler and Bloom have the right to access psilocybin under Washington state’s Right to Try law, a law which permits patients with a terminal illness to access drugs that are currently being researched, but not yet approved. The federal government, she says, is wrongfully interfering with that right.

According to Tucker, who has devoted much of her career to helping pass and reform legislation meant to ease the suffering of those at the end of their lives, states are the primary authority for the regulation of medicine. And yet, in January, Tucker says, when she wrote to the Drug Enforcement Administration, on behalf of Aggarwal, Baldeschwiler, and Bloom, asking them how they should go about accessing psilocybin, the administration wrote back saying they couldn’t because psilocybin is a Schedule I drug on the Controlled Substances Act, the most restrictive category defined as drugs with “no medical use” and a “high potential for abuse.” (Typically, physicians with terminal patients would go straight to a manufacturer to get access to a drug under a state’s Right to Try law, but they needed to write to the Drug Enforcement Administration about the process for access since psilocybin is federally illegal.)

In addition to Washington state, 40 states have Right to Try laws, although they’re all worded slightly differently. (Some use language like “terminally ill” while others say “life threatening,” which could change who qualifies.) Overlaid on top of these state Right to Try laws is a federal Right to Try law, which President Trump signed in 2018. In this case, Tucker and the fellow attorneys are primarily focused on patients’ rights under Washington’s Right to Try law, but are using the federal Right to Try law to bolster their argument.

Both the Washington law and the federal law state that terminal patients can access drugs that are not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration so long as they’ve successfully made it through the first phase of an FDA-approved clinical trial and are currently being investigated. Psilocybin is currently in the final phase of research before FDA approval, and has shown so much promise for treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder that it’s been granted “breakthrough therapy” status by the FDA.

“The DEA just did not know about or did not understand Right to Try and this lawsuit is something of an educational vehicle,” Tucker says. Yes, she says, psilocybin is on the Controlled Substances Act, but in the hierarchy of legislation, The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which Right to Try falls under, trumps the Controlled Substances Act. Tucker says DEA officials just don’t understand that or are behaving as though they don’t. (The Department of Justice declined to comment for this story.)

“I don’t want my diagnosis to be upsetting and dark and hopeless for my kids,” says Baldeschwiler. “So I need to be in a space where I am not hopeless and there is peace. I know for certain if I’m negative and ‘woe is me,’ and desperate and have feelings of like ‘I just want to check out,’ that’s going to make it a hundred times worse.”

Baldeschwiler first got the idea to do psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy from Aggarwal, who she’d found after looking around for more holistic treatment plans in the Seattle, Washington area. Aggarwal discovered what he says is the extraordinary potential of psilocybin to help cancer patients when working with the psilocybin research group at New York University.

Researchers, going back to the late 1950s, found psychedelics such as psilocybin and LSD showed promise for end-of-life distress as well as a host of other mental health conditions, from alcoholism to trauma. Much of this research, however, is not considered valid by the Food and Drug Administration because it did not follow their current protocols.

After Richard Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act into law in 1970, there was essentially a decades-long ban on psychedelic research. It was a landmark study, published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, in 2006 — showing psilocybin holds promise for end-of-life distress in cancer patients — that largely jumpstarted what’s now known as the “Psychedelic Renaissance,” the second wave of psychedelic research in the U.S. since the 60s. The study found that after two or three psilocybin sessions, a majority of participants had significant and positive changes in their mood, while 33 percent rated the experience as the most spiritually significant experience of their life, comparable to the birth of a first child or the death of a parent. Since then, this research has continued with the same results in trials at Johns Hopkins and New York University.

“Many, many patients come to me wanting this,” says Aggarwal of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. “They read about it in the news or in Michael Pollan’s book.” He says it’s hard to predict, but there’s surely millions of terminally ill patients who could benefit from psilocybin therapy. In 2021 alone, an estimated 1.9 million Americans will be diagnosed with cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute. That doesn’t even take into account, says Aggarwal, all the other terminally ill patients, such as those with Lou Gehrig’s disease, whom he also works with.

Susan Patz, a 62-year-old woman with Lou Gehrig’s disease, filed an Amicus brief, a statement which can be filed to the court by someone in favor of a particular side of a case, for this lawsuit. Patz lives in the town of Monroe, Washington, where her husband John is now her caretaker as she slowly loses agency over her body and even her ability to breathe and swallow.

“Because of the ALS, I have had to give up a lot of the activities I was passionate about,” she wrote to the court in a brief filed on May 24th. “I loved gardening, and I used to delight in driving the tractor around our property. I loved to swim at the YMCA five days a week. I loved cooking and trying new recipes. I can no longer do any of those things.” She often stays up until 3 or 4 in the morning, because she can’t sleep; she used to be “foodie,” but now doesn’t want to eat or even see friends for fear that they’ll see her as a “sick person.”

“I am desperate to try something that will work, something that will enable me to experience joy and pleasure again,” she wrote to the court. “If the Right-to-Try laws don’t allow someone like me the chance to try something that may help alleviate my suffering, then what good are they?”

On June 21st, the Department of Justice will file a brief on behalf of the Drug Enforcement Administration. On July 12, the petitioners — Aggarwal and his patients — will be given the opportunity to reply. And then, likely in September, the oral argument will take place in which, Tucker says, they may get their first insights into where the court stands on the case. She’s hopeful that perhaps they won’t even get that far, though, because the Drug Enforcement Administration will reach out with the intention of finding a resolution.

Either way, Tucker says, if the case passes, the next doctor and patient who want access to psilocybin for end-of-life distress shouldn’t need to take it to court again. If they succeed in Washington, then, she says, doctors and patients in states with Right to Try laws should be able to access psilocybin.

There’s many unknowns, however, about how doctors and patients would go about notifying the DEA when they’re going to conduct psilocybin therapy — and how they would access the psilocybin itself. Currently, under Right to Try laws, doctors don’t need government approval at all — they can go straight to manufacturers to request access to a drug that’s under investigation for their patient. But the process might be different for psilocybin and a host of practical issues exist, too, such as that it’s difficult to find federally-licensed labs making synthetic psilocybin as there’s no publicly available directory. At this point, Tucker says, they’re just focused on taking things in “small bites.”

“It kind of kills me that I have to be dying to even possibly have access to this medicine when I think it could be incredibly helpful for so many people that maybe don’t fall into that category,” says Baldeschwiler. “I truly, truly am hoping that we have some open minds and open hearts with regards to the DEA and that they honor the intent and the letter of the law because we fall within it.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

by Sydni Ellis

Doulas are compassionate people who help others navigate some of life’s biggest transitions. Some doulas provide support and care to women bringing babies into the world, while others help ease individuals through the difficult and emotional passing of a loved one. These people are known as death doulas, or end-of-life doulas.

Recently, Riley Keough — granddaughter of Elvis and Priscilla Presley — announced on Instagram that she recently completed The Art of Death Midwifery training by Sacred Crossings and is on her way to becoming a certified death doula. In the post, she said, “I think it’s so important to be educated on conscious dying and death the way we educate ourselves on birth and conscious birthing. We prepare ourselves so rigorously for the entrance and have no preparation for our exit.” Riley’s decision to become a death doula comes almost a year after her brother, Benjamin, died by suicide in July 2020 at the age of 27.

Many other women have decided to take on this noble role of helping people in their final days. There are various courses that will certify you as a death doula, including the International End of Life Doula Association (INELDA). This association trains doulas to a high standard of professionalism, where they learn how to listen deeply, work with difficult and complex emotions, explore meaning and legacy, utilize guided imagery and rituals, assist with basic physical care, explain signs and symptoms of last days, guide families through the early days of grieving, and more. We talked to a few death doulas to find out more about this unique profession.

Dana Humphrey, a New York-based life coach and death doula who is certified through INELDA, told POPSUGAR, “Death doulas help the active dying transition with ease. We help them have difficult conversations with their loved ones, so they may say goodbye with grace. We help them figure out their legacy project and help them complete it. We add presence to the dying during a busy hospice environment. We also provide support to the family if they are having a hard time with the transition.”

Death doulas are the people that hold the hand of a dying person, ask them about their wishes and try to make them happen, and advocate for them every single day, according to Humphrey. Some of the things she might do include asking the dying person what mood they would like to see and feel when the family comes to visit and then setting that tone, like by having guests take a minute to sit down and move to a place of gratitude before visiting their loved one. Or she might have visitors meet in a “fun station” to put on funny hats or bedazzle themselves in glitter to add lightness in the room.

Suzanne O’Brien, RN, is the founder of the International Doulagivers Institute, who’s mission is to provide awareness, education, support, and programs to communities, patients, and their loved ones worldwide to ensure the most positive elder years and end-of-life process. She told POPSUGAR that a death doula is “a nonmedical person trained to care for someone holistically (physically, emotionally, and spiritually) at the end of life.” This job “recognizes death as a natural, accepted, and honored part of life.”

After years of working as a hospice and oncology nurse, O’Brien felt unfulfilled working hospice, where nurses manage the dying patient’s care but teaches the family how to do the actual 24/7 care. She said she typically didn’t have enough time with patients on hospice as she was only allowed about one hour, once a week with the patient, and she encountered many families afraid of death. This helped her realize that death is “a holistic human experience and not a medical one,” and she wanted to become a death doula instead.

“Every day brings different needs, but it will always center around support,” O’Brien explained. “I will get called by a family whose loved one was just given a terminal diagnosis and they do not know what to do next, or a family whose loved one is actively transitioning and needs more help in the home. [I also get] many calls from families and community members looking for education and resources to help facilitate the most peaceful passing possible.”

Donna Janda, Thanadoula practitioner (another term for death doula) and registered social worker, and Ananda Xela, Thanadoula practitioner and life coach with over 20 years’ experience in social work who has trained with INELDA, both founded Embracing Daisies to empower clients to “see the cycle of life and death not as something to simply rise above but as something to move through with soul and awareness, creating a living and lasting legacy.” They chose this profession to deal with their own feelings about death, as it helped them let death inform the fullness of their own existence, as well as to become part of this burgeoning field in which they didn’t see themselves or other BIPOC well-represented.

“There can be different ways of seeing and dealing with death, and when we talked to both clients within our Black communities and other doulas outside of our communities, we noticed the differences in approach and practice,” Janda and Xela told POPSUGAR. “A lot of the work that takes place in our own communities involves more emphasis on creating comfort around the idea of just talking about death in an honest and open manner before reaching the point of being able to plan for it. It can be a challenge for people who are already in vulnerable positions, historically and personally, to find the desire to face death and accept the idea that it can create more joyful living and offer more control over one’s own narrative — something that is often denied to marginalized peoples.”

Janda and Xela said, “To us, a death doula is someone who can hold space and offer support to both an individual and their loved ones in various areas all along the path between living and dying — from the parts where death seems unimaginable to the parts where it seems inevitable.”

As Thanadoula practitioners, these women hope to aid their clients in seeing that “life and death are connected and give meaning to each other.” They believe that deaths can matter as much as lives, and their job as death doulas is to help patients “discover, create, articulate, and manifest your heart’s wishes.” They also give families space to grieve by taking care of some of the more practical aspects that come from someone nearing the end of life.

If you are thinking about becoming a death doula, you should have a passion for other people, an open-mindedness about death, and the courage to help people through difficult times. O’Brien said, “People often ask, ‘How can you do that work? It must be so depressing.’ I have to say that it is the exact opposite. Working as a death doula has been the hardest thing I have ever done, but the most fulfilling and rewarding. It is an honor and privilege to work with families at this sacred time. What you learn from those at the end of life is wisdom that teaches us about life. It is the best decision I have ever made.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

By Madeleine Burry

The loss of a loved one isn’t the only life event that leads to grief, and grieving isn’t just about hard crying, deep sadness, and other ovewhelming emotions. “We grieve and experience loss at every life transition,” Emily Stone, PhD, owner and senior clinician at Unstuck Group, a consulting organization for churches. That grief can be spurred on by sad or tragic events (a house fire, an infertility diagnosis, the loss of a job) and even by more joyous moments, like a child graduating kindergarten or going off to college, she says, because of what’s lost due to the change.

Opening up to the possibility that there are various types of grief is important for healing. “When we can recognize and name what’s going on emotionally inside of us, we can be kinder to ourselves during the process,” California-based therapist Skylar Ibarra, MSW, LCSW, tells Health. “Once they were able to see their grief for what it was, they were able to start healing,” she says.

Here, are some of the lesser known varieties of grief a person may experience, what they feel like, and what can cause them.

Expecting loss or change can lead to anticipatory grief. With it, “we end up essentially experiencing the loss before it even happens,” Robin Hornstein, PhD, a licensed psychologist and co-owner of the Philadelphia-based mental health practice Hornstein Platt & Associates, tells Health.

That can have a destructive element. Hornstein recalls a person diagnosed with a disease in childhood who anticipated dying young. Now, the individual is in their 80s. “Approaching their actual death, as they are not well, has made them understand how much time they have spent worrying,” Hornstein says.

But there’s a reason people engage in this behavior: It provides a sense of control. “Anticipatory grief is our mind and body’s way of preparing for the loss. We do this to make the ‘after’ of the loss a bit less intense-and it works,” Ibarra says.

Grief doesn’t always happen immediately: Sometimes people aren’t in a place to process loss, Stone says. That can be because of cognitive or emotional reasons, she notes, such as a young age or trauma. “I often see delayed grief in clients when they hit points of transitions in their life: at their wedding, at graduation, at the birth of a child,” Stone says.

This type of grief “can feel overwhelming, confusing, and unwarranted at first, since we don’t immediately recognize that we are grieving a long-ago loss,” Ibarra explains.

With this type, it may seem to people around you-and yourself-as if you’re not grieving something you feel you should be grieving, or your grief doesn’t look like the grief of people around you. But there can be a lot of reasons for not having a typical response, Ibarra says.

Shock, a feeling of relief that someone’s free from pain, or lack of understanding how to grieve-these can all lead to absent grief, Hornstein says. “Sometimes it could be linked to already processing the loss, such as an abusive parent or someone who has been ill for a long time,” she notes.

A person might even grieve without realizing it. “Many people think of grief as uncontrollable tears, ripping clothing, not being able to get out of bed, etc.,” Ibarra says. But it can also manifest as anger, difficulty concentrating, or intense worry, she says. “These aren’t the typical grief reactions we see in popular media, but they are what I see in my office,” she notes.

“Inhibited grief is usually classified as grief that someone is consciously attempting to quash,” Ibarra says. This can look like overworking or being excessively busy, Hornstein says. “Sadly, this does not stop the grief, just twists it into a different form that is harder to work through,” she says.

Ibarra compares it to ignoring a pebble in your shoe: Leave it in place instead of removing it, and a blister will form. “So not only do you now have to deal with the pebble, but the blister, too,” she says.

This type of grief isn’t recognized by our culture, Stone notes. That can be because people don’t think the event is worthy of mourning or due to your circumstances. For example, you may not be fully and openly mourn the loss of a lover in an extramarital affair, she points out.

It can also be a kind of grief that feels hard to explain, Hornstein says. “I once literally cried over a death on a long-running TV show and felt an acute sense of sadness,” she says. But taking off of work due to Poussey dying on Orange Is the New Black might not make much sense to others, she says.

“There are so many situations where a loss is not recognized or just glazed over by society.” Stone says. “This can be a very dark and lonely journey for the person experiencing the loss.”

People may experience environmental grief tied to the worsening climate, Ibarra says. “Another one that many people experience is perpetual grief after the diagnosis and living with a long-term disability,” Ibarra says. Or, people may grieve over the loss of an imagined future (this can occur due to an infertility diagnosis, the loss of a job, and so on).

There can also be unexpressed grief that’s intergenerational, Hornstein notes. She gives the example of survivors of genocide victims, who will never know their predecessors. “They might harbor a sense of fear/doom that this could happen again or is still happening in a different way and have grief symptoms that are expressed in familial patterns,” Hornstein says. It’s something that’s seen in BIPOC people in the United States, she notes.

“This type of grief is hard and needs unpacking so that feelings can be expressed, and actions taken to be more present and find ways to feel safe,” Hornstein adds.

Coping strategies may differ based on the type of grief a person experiences. “If someone is experiencing a delayed grief reaction because they are in crisis, then the crisis needs to be addressed first,” Ibarra says.

But there are some general strategies that apply to all types of grief, Hornstein says. These include:

“If you notice you are grieving, be compassionate, allow for time, drop the need to be perfect at it or anything else, do not judge the quality or length of time you grieve, and honor the feelings,” Hornstein says.

It can be cathartic and healing to create a memorial for the person or thing you’ve lost, Ibarra says. “This may be a letter you burn or an altar you maintain for years. It allows us to accept the reality of the loss, create a space to feel our feelings, and to build a new life moving forward-all critical parts of the grieving process,” she says.

That can take the form of crying over flowers instead of missing someone who has died, Hornstein says. “Allow the grief to lead you where you need to be,” Hornstein says.

“No one escapes grief,” Hornstein says.But the process-though normal and necessary for long-term health-can be challenging and painful, Ibarra says. And the kind of grief you feel over one thing or event may be very different than that of another, so your response may feel unfamiliar and worrisome. “You deserve support as you navigate this experience,” Ibarra says. That’s true for anyone experiencing grief, she says. Still, there are a few indicators that you should reach out for help.

“You do not need to be broken and nothing needs to be wrong with you to seek the help of a professional,” Ibarra says-that is, if you think you’d benefit from support, seek it out.

If you are not able to go through the ordinary routine of life-taking regular showers, showing up to work on time, and so on-it’s a good idea to seek help, Hornstein says. Difficulty sleeping or an inability to eat are also cues to reach out for support, she says.

Certain feelings-such as intense, out-of-control anger or prolonged hopelessness-can be a sign that you should seek professional help, Ibarra says.

Reach out to professionals if you experience guilt over being alive or a desire to self-harm, Hornstein says. But keep this in mind: “You do not need to wait until things get really bad to seek help,” Ibarra adds.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Death looms larger than usual during a global pandemic. An age-friendly community works to make sure people are connected, healthy and active throughout their lives, but it doesn’t pay as much attention to the end of life.

What might a death-friendly community ensure?

In today’s context, the suggestion to become friendly with death may sound strange. But as scholars doing research on age-friendly communities, we wonder what it would mean for a community to be friendly towards death, dying, grief and bereavement.

There’s a lot we can learn from the palliative care movement: it considers death as meaningful and dying as a stage of life to be valued, supported and lived. Welcoming mortality might actually help us live better lives and support communities — rather than relying on medical systems — to care for people at the end of their lives.

Until the 1950s, most Canadians died in their homes. More recently, death has moved to hospitals, hospices, long-term care homes or other health-care institutions.

The societal implications of this shift are profound: fewer people witness death. The dying process has become less familiar and more frightening because we don’t get a chance to be part of it, until we face our own.

In western cultures, death is often associated with aging, and vice versa. And a fear of death contributes to a fear of aging. One study found that psychology students with death-anxiety were less willing to work with older adults in their practice. Another study found that worries about death and aging led to ageism. In other words, younger adults push older adults away because they don’t want to think about death.

A clear example of ageism being borne out of a fear of death can be seen through COVID-19; the disease gained the nickname “boomer remover” because it seemed to link aging with death.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) framework for age-friendly communities includes “respect and social inclusion” as one of its eight focuses. The movement fights ageism via educational efforts and intergenerational activities.

Improving death-friendliness offers further opportunities to improve social inclusion. A death-friendly approach could lay the groundwork for people to stop fearing getting old or alienating those who have. Greater openness about mortality also creates more space for grief.

During COVID-19, it’s become clearer than ever that grief is both personal and collective. It’s especially relevant to older adults who outlive many of their peers and experience multiple losses.

The compassionate communities approach came from the fields of palliative care and critical public health. It focuses on community development related to end-of-life planning, bereavement support and improved understandings about aging, dying, death, loss and care.

The age-friendly and compassionate communities initiatives share several goals, but they don’t yet share practices. We think they should.

Originating with the WHO’s concept of healthy cities, the compassionate communities charter responds to criticisms that public health has fallen short in responding to death and loss. The charter makes recommendations for addressing death and grief in schools, workplaces, trade unions, places of worship, hospices and nursing homes, museums, art galleries and municipal governments. It also accounts for diverse experiences of death and dying — for instance, for those who are unhoused, imprisoned, refugees or experiencing other forms of social marginalization.

The charter calls not only for efforts to raise awareness and improve planning, but also for accountability related to death and grief. It highlights the need to review and test a city’s initiatives (for instance, review of local policy and planning, annual emergency services roundtable, public forums, art exhibits and more). Much like the age-friendly framework, the compassionate communities charter uses a best practice framework, adaptable to any city.

First, it comes from the community, rather than from medicine. It brings death back from the hospitals and into the public eye. It acknowledges that when one person dies, it affects a community. And it offers space and outlets for bereavement.

Second, the compassionate communities approach makes death a normal part of life whether by connecting school children with hospices, integrating end-of-life discussions into workplaces, providing bereavement supports or creating opportunities for creative expression about grief and mortality. This can demystify the dying process and lead to more productive conversations about death and grief.

Third, this approach acknowledges diverse settings and cultural contexts for responding to death. It doesn’t tell us what death rituals or grief practices should be. Instead, it holds space for a variety of approaches and experiences.

We propose that age-friendly initiatives could converge with the work of compassionate communities in their efforts to make a community a good place to to live, age and, ultimately, die. We envision death-friendly communities including some, or all, of the elements mentioned above. One of the benefits of death-friendly communities is that there isn’t a one-size-fits-all model; they can vary across jurisdictions, allowing each community to imagine and create their own approach to death-friendliness.

Those who are working to build age-friendly communities should reflect on how people prepare for death in their cities: Where do people go to die? Where and how do people grieve? To what extent, and in which ways, does a community prepare for death and bereavement?

If age-friendly initiatives contend with mortality, anticipate diverse end-of-life needs, and seek to understand how communities can indeed become more death-friendly, they could make even more of a difference.

That’s an idea worth exploring.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!