by Robert Barron

Surrounded by his many friends and loved ones, Ernie Sievewright finally died with dignity in his Crofton home on Jan. 15.

After wading his way through a long bureaucratic process that began late last spring, the wheelchair-bound senior from Crofton was finally allowed to legally commit suicide with the assistance of a physician on Sunday under Canada’s new Medical Aid in Dying legislation, which became law in June.

His death follows the physician-assisted suicide in their home on Jan. 11 of his beloved wife Kay.

Kay had been suffering for some time from complications of multiple sclerosis and other medical issues at a nursing home in Duncan.

That makes Ernie and Kay among the first couples to successfully access doctor-assisted suicide in Canada since the Supreme Court of Canada voted unanimously to strike down the federal prohibition against it in Bill C-14.

Bill C-14 restricts physician-assisted deaths to mentally competent adults who have a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability.

Sievewright suffered from cauda equina syndrome, a serious neurological condition that causes loss of function of nerve roots along the spinal cord.

Before his death, Sievewright said the quality of life he and Kay had was continuing to deteriorate rapidly, so they decided that death was preferable.

“It was very difficult for me to see Kay in pain all the time, and I live at home alone in a wheelchair dealing with the pain of my own illness and counting on friends to come by and pick me up when I fall,” he said.

“There’s no value in our lives anymore, so we had to ask ourselves what was the point of sticking around. We didn’t want to minimize our decision, but it was well thought out and we had discussions with friends and family. We all agreed that this was the best for both of us.”

But the approval process was long, and both had to meet with countless doctors and other specialists for their assessment and approval, so it took many months before they were finally given the green light.

Both died quickly and painlessly by lethal injections delivered by a doctor.

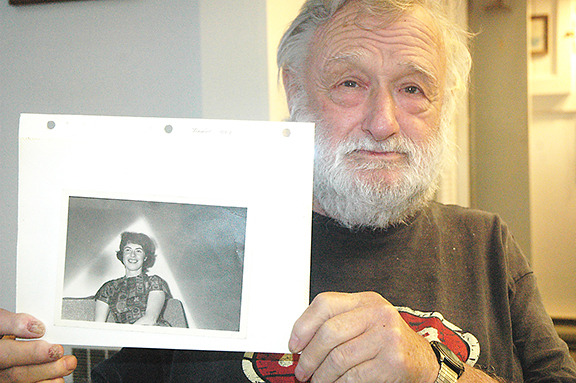

Sievewright invited the Cowichan Valley Citizen to his home just 36 hours before his scheduled death.

It was the happiest this reporter had seen him in the four months since I first met the Irishman with his infectious grin.

During that encounter in October, Sievewright was frustrated with all the meetings and consultations with doctors and delays he and Kay were facing in the process.

All that was in the past in the hours after he held Kay’s hands on Jan. 11 while the lethal injection was being administered to her.

“I feel really, really good,” he said at his kitchen table while friends looked on.

“I was a little upset that we couldn’t go together, but now I’m glad that Kay went first and I was with her at the time. She went so peaceful and beautifully and it was a great relief for me to see that. I’m not frightened now of my own death.”

Sievewright said he still wished the process could have been easier and quicker, but all the doctors and medical officials he and Kay dealt with were very kind, and did the best they could for the couple under the new law.

Dr. David Robertson is the co-chairman of Dying with Dignity Canada’s physicians advisory council.

He said there are no day-to-day records of exactly how many people have died through doctor-assisted suicides across Canada since Bill C-14 was legislated in June.

But Robertson said it’s been estimated that approximately three doctor-assisted deaths have been occurring a week on Vancouver Island for the last six months.

“I think the numbers across Canada are steadily increasing, particularly on the Island which has a long history of activism on this issue,” he said.

Robertson said it’s a fact that some doctors and nurses have personal views and are reluctant to participate in doctor-assisted deaths, “but many others are very willing”.

He said there are currently only 12 physicians on the Island who have taken the required training to perform the deaths, and many more are in the process of completing the education.

But Robertson said the numbers of medical staff who have the training and expertise have little to do with the amount of time it takes for people to make their way through the medical bureaucracy.

“We have the same requirements in B.C. as the rest of the country, and there are numerous documents and forms to be filled out and steps that have to be taken,” he said.

“There are very high standards to fit the criteria, so this is no simple process. It’s not a decision that patients or the medical community take lightly. We’ll continue to monitor physician-assisted suicides across the Island and the country and develop the process as we go to better fit the needs out there.”

As for Sievewright, he was just happy to finally get to the end of his long journey.

“Kay said she’d have the boat in the water with a full bait bucket and at least one dog on board waiting for me when I get there, and we’ll go fishing on flat and calm seas,” he said with a smile.

“I’m hoping that this really happens because it would be fantastic. Kay and I have lived a rich and full life. All is now in order, and we’re ready to move on.”

Complete Article HERE!