[A] close friend passed away recently — no doubt among the first people to take advantage of California’s End of Life Option Act. Signed into law in 2015 and in effect as of June 9, 2016, the law gives terminally ill adults who have only six months to live the ability to request and obtain life-ending medication.

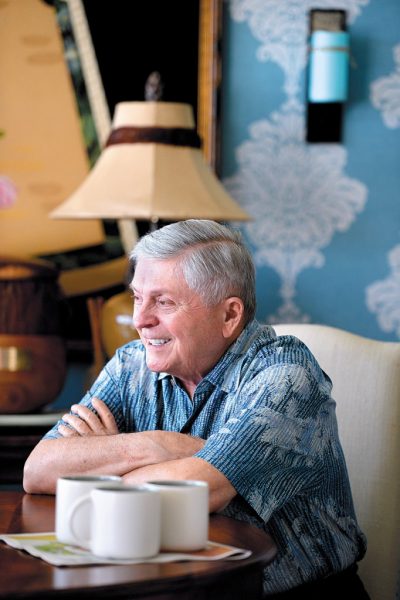

My friend had a virulent form of prostate cancer. He lived with it for a few years, but when the tumors began to invade almost every part of his body, he entered hospice and requested the drugs. He wasn’t sure he would take them, but when the pain kept getting worse and it became obvious that the end was near, he made his decision. He died peacefully with his family at his side.

Along with California, only Oregon, Washington, Vermont, Montana, Colorado and Washington, D.C., support medical aid in dying. Now, with the recent tide of conservatism, opponents of medical aid in dying are moving quickly to attack the option.

The law was challenged in Riverside in August, but a judge denied the request for an injunction filed by a group of anti-choice physicians. The Montana House of Representatives was considering a bill that would have allowed the state to execute doctors for prescribing end-of-life medication. The bill was narrowly defeated on March 1. The nominee to the Supreme Court, Judge Neil Gorsuch, wrote a book on how to defeat death-with-dignity bills, suggesting the option violates the Constitution.

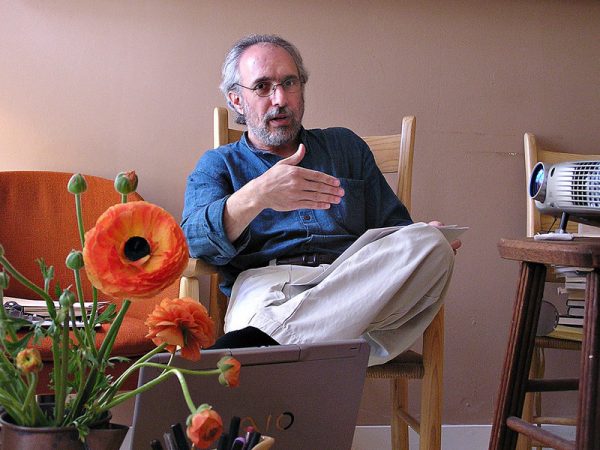

I have always been a strong advocate of death with dignity. I first became involved in this issue several years ago, when my mother found out she had ALS, a devastating neurological disease. She was 77, a refugee from Hitler’s Germany, and knew what was in store. She asked me to help her.

I spoke to her doctor, who said he might be able to “put her under” if her distress became unbearable. We left it at that, until hospice became involved. When I told them about the agreement, they said they could not support it and would now monitor the amount of morphine in the house.

At a loss, I did research and found an organization called Compassion & Choices. They came to visit my mother and me, and told us what she could legally do to take control of her death in New York. She would have to acquire the appropriate life-ending medication, and take it while she was still functional. Like most patients in her situation, she was relieved to know what she could do, but ended up dying on her own.

All religions take a stand on this issue. There is no question that Jewish law and tradition reject suicide, prohibit murder and accept pain and suffering as a part of life. The tradition is less clear when it comes to a person who is already dying of a terminal illness.

The Talmud tells the story of the death of a great sage, Rabbi Judah Ha-Nasi. The rabbi is suffering greatly but his students are praying with fervor in the courtyard to keep him alive. Out of compassion for his suffering, his maidservant drops a jar from the rooftop, stunning the students into silence, at which point the rabbi dies.

This story has been used to justify the removal of life support, validating the patient’s right to a death with dignity, without pain and suffering. Judaism also usually considers palliative care an appropriate measure if someone is suffering at the end of life. But most Jewish traditions end there.

If we allow caregivers to remove life support, and to provide palliative care, why can’t we give the terminally ill the tools for a peaceful death? The states that support the legislation have very strict safeguards in place, and patients must take the life-ending medications themselves, after they have been prescribed by a physician for that purpose.

My friend found great comfort knowing he had the life-ending medication, even if he wasn’t sure he would take it. He told me it freed him from anxiety, so he could spend his last days focusing on what meant most to him — being with his family and his friends.

Complete Article HERE!