— A Practical Perspective on Good Deaths

Death is considered taboo in the Western world and many other cultures. With the world’s population aging rapidly, we cannot afford to turn a blind eye toward the process of dying. We owe it to ourselves and our loved ones to advocate for the tools, knowledge and spaces necessary to prepare for a good death.

At the age of 87, my father passed away from cancer in Calgary, Canada. He had multiple myeloma, an illness that made his bones very fragile. He was bedridden for the last nine months of his life. Instead of hospice, he wanted to spend his remaining time at home for several reasons. We could be with him 24/7; he could be in familiar surroundings, eat his favorite foods and watch his favorite shows; and we could retain control over his care and manage it according to his wishes.

My mother, sister and I supported his decision. My 80-year-old mother managed the home and cooking. I scheduled appointments and managed his day-to-day care. Since this was during the COVID pandemic, my sister could work from home and would pop up between meetings to feed him. My sister and I would alternate doing night duty. It was the best of times; it was the worst of times. It brought us all closer; it was frightening and exhausting.

In the final days, I felt myself woefully unprepared to guide a loved one through this inevitable journey in a gentle and reassuring manner. I wondered why our society and culture do not offer us more support. Death needs to be made into a less traumatic and more normalized process.

We are woefully underprepared…

Globally, the population is aging; the number of people over 80 is expected to increase dramatically from 137 million in 2017 to 909 million by 2100. In Canada, more than 20% of the population is over the age of 65. In the US, that number is approaching 18%.

Some 61 million people the world over died in 2023. That number is expected to reach 120 million annually by the end of this century. The upcoming decades will see the steepest rise in the number of annual deaths in possibly all of our human history. Death should be an important public health topic — both globally and nationally.&

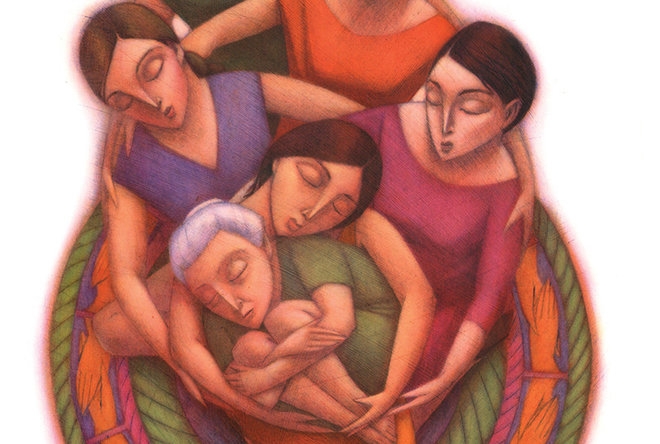

For the experience of birth, there is an abundance of support and enthusiasm. There are informational books like the classics What to Expect When You’re Expecting and Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Newborn and Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth. More are published each year. Prenatal classes are found in numerous hospitals and community centers. Some stores cater specifically to new parents, offering necessary as well as cute items. There are celebrations like baby showers. Grandmothers and mothers and aunts and sisters and friends share their excitement, wisdom and help. There are hospitals and obstetricians. And there are doulas and midwives.

For the experience of death, we are sad, frightened and alone. There’s not enough support, even though experiencing death — either others’ or even our own — is as much a part of our existence as birth. In fact, one could argue that death is the more universal experience. Yes, we’re all born, but we don’t even remember it later. In contrast, many of us are even conscious and coherent in our final days before death. Apparently, just before he died, Oscar Wilde had the wherewithal to say, “Either that wallpaper goes or I do.” While not all of us give birth, we all die. We need to be better prepared for death.

…but we don’t have to be

We don’t do too badly in terms of books on the subject of death. While there’s not yet a What to Expect When You’re Dying, there are several excellent books on the practical aspects of death: Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal; Sherwin Nuland’s How We Die; Margaret Rice’s A Good Death; Katy Butler’s The Art of Dying Well; and Sallie Tisdale’s Advice for Future Corpses. Such books can help to introduce, inform and normalize the concept. They can help us see death not just as something to avoid, but as something to prepare for.

There are no classes on how to die well, but there could be. Just like how we have prenatal classes, we could offer pre-death — or to be parallelly Latin, “premortem” — classes, for anyone experiencing death. Premortem classes would be taken when we know death is impending, or even beforehand to motivate us to make the most of our remaining time. To make them accessible, these classes could be offered in hospitals and community centers just like prenatal classes.

True, death means the loss of a person instead of a gain. But isn’t that even more of a reason to have a celebration before dying, to appreciate what is precious while we still have it? There is rarely a pre-death celebration, particularly in the West. End-of-life celebrations can bring the dying and their loved ones together to reminisce, reaffirm and say goodbye. In some communities in South India, the 60th and the 80th birthdays have long been celebrated with special fanfare. There is a puja (prayer) for the guest of honor, followed by a feast and party attended by a large number of family and friends. The Western world is now thinking of “living funerals” — or the happier term, “celebrations of life.” Perhaps we should embrace them wholeheartedly.

Preparation for death could also involve a bit of a shopping-and-social experience. There are already “Death Cafés” where people meet in a café to talk about death. There is potential to expand this to a full-time, accessible space with books on philosophy, faith, how to have a good death and how to guide loved ones through the process. There could be support group meetings for the dying as well as their companions. Conversation groups on a variety of death-related topics and lectures from experts could offer those premortem classes. Given the growing demand foreseen over the course of this century, this has the scope to develop into a purposeful space for preparing for death.

Professional care shouldn’t end at the hospital

While bookstores and cafes can offer space to talk about death, there is still a demand for experts to coach us through the process. There are palliative care doctors, but only in cases of incurable diseases and not for cases of regular deaths. Hospices are few in number and are only open to those with a terminal illness and a prognosis of less than six months. As a society, we need to consider and plan spaces where people — especially those who are alone — can die in comfort and with easy access to professional expert care.

Over the past 20-some years in the US, the percentage of deaths at hospitals has decreased from 48% to 35.1%. The percentage of deaths at home has increased from 22.7% to 31.4%. In a 2013 survey in Canada, 75% said they would prefer to die at home. Governments too prefer to have us pass away at home, as it lessens the burden on nations’ hospitals and healthcare systems. Passing away at home may be what most of us want — in a familiar place, surrounded by our memories and family. How nice it would be if we could also have a death expert on hand. Just as we have a midwife to assist us in the birthing process, we could have a midwife to help us in the dying process. Surprisingly, such people exist.

A death midwife or doula is simply defined as a person who assists in the dying process. There are already death midwife associations in several countries (e.g., Canada, US, UK), such as the International End-of-Life Doula Association (INELDA). Death midwives can perform a variety of services. Many provide information and logistical assistance, such as death planning and funeral planning.

I envision a broader and more intimate role. I see a death midwife as similar to a birth midwife, someone who is very hands-on and who has a link with a doctor. A comforting, compassionate and yet objective presence who has helped many die well. It would involve assisting with physical as well as emotional end-of-life care. Just as the birth midwife helps both the mother and the child, I see the death midwife as helping both the dying and their companions. Death midwives can give guidance in accordance with the wishes of the family and, most importantly, in accordance with the wishes of the dying. They can hold our hand till the gate.

We owe it to ourselves

Given the unprecedented numbers that will be dying in the coming decades, it would be wise for societies at large to treat death as a public health issue. And given that none of us is likely to escape death, it behooves us individually to advocate for support systems – such as informative literature, preparatory classes, conversation groups, dedicated products and spaces, and accessible death experts and midwives. A good death may well be possible if we prepare to evolve in such a manner. We owe it to our parents, ourselves and to our children.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!