— Death doulas help people navigate end-of-life. “I say we work in the in-between.”

By Renee Wilde

David Copeland remembers his great grandmother’s death.

“She died with all of us around her, singing to her, and that’s how she slipped away from here,” he said. “And I want to slip away the same way.”

Copeland is the owner of Live Without Regrets. He works as a death doula guiding others through the end-of-life.

Only 36% of Americans have written or talked to loved ones about their end-of-life plans, according to the National Funeral Directors Association. Yet, everyone will have the experience of dying.

“I say we work in the in-between. In between life and death. In between joy and sorrow. We work in between questions and answers. We’re navigating that.”

Having these difficult conversations, and coming to terms with our impermanence can be scary, sad, and mysterious, and it provokes anxiety for many.

“I say we work in the in-between. In between life and death. In between joy and sorrow. We work in between questions and answers. We’re navigating that,” Copeland said.

“If I can be, I try to be present for the death and the transition,” he said. “If you want a vigil, if you want somebody to stand next to you, if you want songs or singing, and all the things that come with vigiling.”

Copeland also helps the dying navigate conversations with friends and family, and examine the kinds of legacy they want to leave behind.

“Sometimes it’s writing letters to friends, or writing letters to kids that may not be in your life. You’re estranged, but this is what they wanted to give you when they passed – here you go, directions,” he said. “And it’s just good for people to take control of that part of their dying experience and the life they lived.”

Even medical professionals, whose jobs require delivering difficult news, can struggle to talk with their patients about dying. So part of Copeland’s role as a death doula is working with the dying to help them understand what’s going on.

“We have the ability to have real conversations,” Copeland said, giving an example. “Alright, they say you have pancreatic cancer and have six weeks (to live). Well what does that mean? What to expect? Some folks want that to know that so they can prepare, some people don’t. They don’t know how to have those conversations with the health care system. “

Copeland is also an advocate for the LGBTQIA+ community, who have unique needs that often require them to not only grapple with death, but also dignity and identity.

“You have aging trans people who go back in the closet when they go inside of hospice centers and nursing homes because they won’t be able to keep themselves,” he said. “I really push for them to have a representation for disposition of the body. It helps so that the next of kin don’t come in and do whatever they want to you, and dead name you and misgender you and do all the things that you didn’t want.”

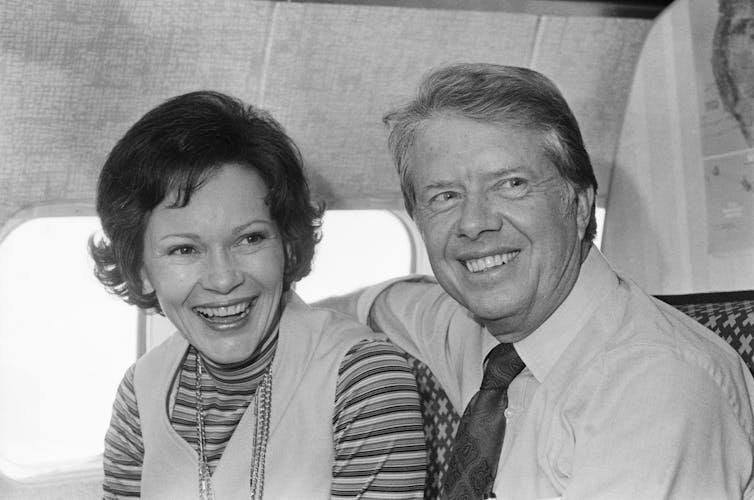

Michael Kammer said the five important things family and friends can say to a loved one who is dying are: I love you, I forgive you, forgive me, I’m going to miss you, and goodbye.

Michael Kammer, a former medical social worker at Hospice of Dayton, has guided many people through the end-of-life. With his unique background as a former chaplain, massage therapist, and social worker, he has helped the dying navigate the mind, body and spirit.

Kammer said that when people come into hospice sometimes it’s already too late to have these conversations.

“The patient comes in and is unresponsive, so we are working with the family. But, of course, it’s still important for the family to communicate with the patient, even when the patient can’t communicate back,” Kammer said. “Because we all believe in hospice care that they hear, that the patient hears and at some level understands.”

Kammer said the five important things family and friends can say to a loved one who is dying are: I love you, I forgive you, forgive me, I’m going to miss you, and goodbye.

He said he would also add a sixth: that it’s OK to let go.

“It’s amazing to see how when just the right person gets there and has that conversation with the person who is dying, they’re often able to slip away, sometimes very quickly,” Kammer said.

Like Copeland, Kammer’s work with the dying has led him to come to terms with his own mortality. “Well, for one thing I no longer fear my death. I’ve imagined my death in every imaginable way possible.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!