This VR experience puts doctors in a dying man’s shoes

By Luke Dormehl

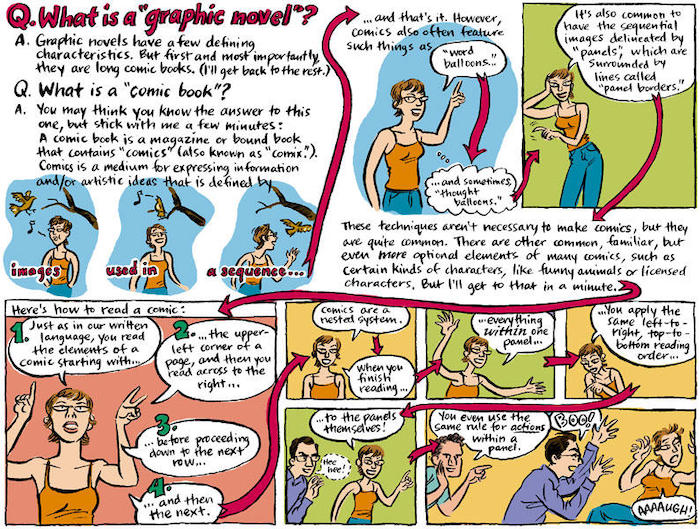

Virtual reality may be able to transport you to spectacular other worlds, but a large part of its promise is the ability to also put you into the shoes of other people. In doing so, the hope is that VR could help make us more empathetic, since it gives us the ability to literally experience life from another person’s perspective.

That’s what VR studio Embodied Labs hopes to do. Based in Los Angeles — arguably the entertainment capital of the world — Embodied Labs wants to use cutting edge virtual reality to do something more than provide escapism. It wants to use it to promote empathy. And it wants to do it in such a way that can help train tomorrow’s caregivers.

We’ve previously covered Embodied Labs’ work creating a virtual experience intended to simulate the effects of Alzheimer’s disease. Called “The Beatriz Lab: A Journey Through Alzheimer’s Disease,” it follow the fictitious character Beatriz, a math teacher in her 60s, as she grapples with the neurodegenerative disease. Now Embodied Labs is back with another virtual training tool, this time designed to function as an end-of-life simulation for educating staff and medical students in hospices, hospitals, and universities. It’s currently being used at the Gosnell Memorial Hospice House in Scarborough, Maine, as well as by medical students at the University of New England.

Meet Clay

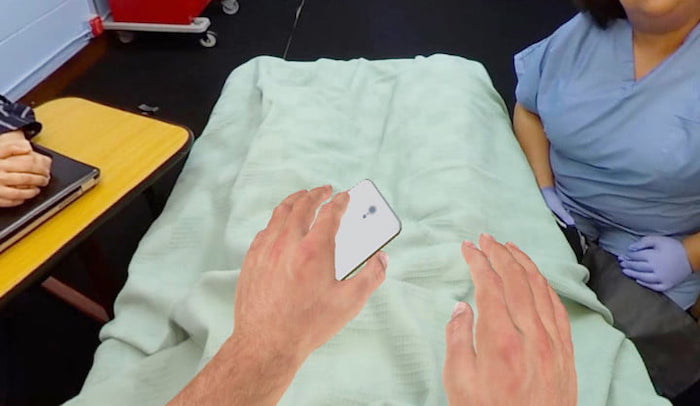

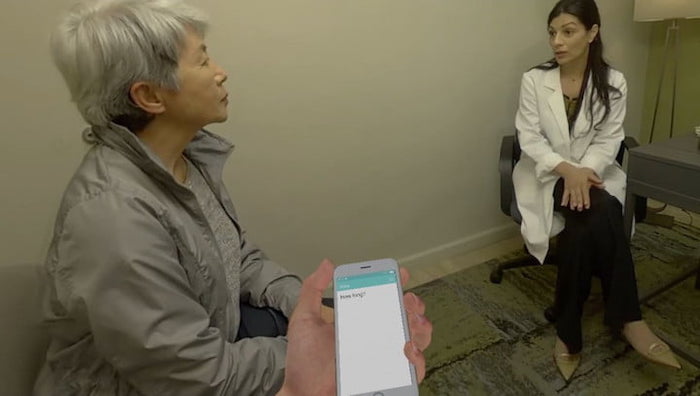

The 30-minute simulation places users in the role of “Clay,” a 66-year-old lung cancer patient in need of hospice care. During the course of the VR story, Clay has important conversations with family, suffers a fall that puts him in the E.R., and eventually winds up in hospice care. Through simulating physical changes in virtual reality — such as how Clay’s skin alters and his senses dull — the user also gets to feel some approximation of what it would be like to experience end-stage cancer. By the end of the experience, Clay’s eyesight becomes dim as his life comes to a close. For anyone who associates VR predominantly with gaming, the effect is surprisingly poignant.

“The embodied experience includes receiving a terminal diagnosis from your oncologist, counseling from your case manager, and care from your hospice provider and family, and ultimately, it involves reaching the end of your life,” Erin Washington, co-founder and COO at Embodied Labs, told Digital Trends. “By embodying Clay, people gain insights into challenges faced by patients and families when curative treatment is not available, learn how hospice care supports loved ones, and explore the physical, spiritual, and mental changes that may occur at end of life.”

Through its painstakingly created and very human VR experiences, the company has cornered the market on a type of next-generation training tool. It provides an experience that caregivers or clinicians cannot get simply by reading textbooks.

Through its painstakingly created and very human VR experiences, the company has cornered the market on a type of next-generation training tool. It provides an experience that caregivers or clinicians cannot get simply by reading textbooks.

“Embodied Labs creates immersive training and wellness tools for healthcare students, and for professional and family caregivers, so they can feel more empowered and confident in having the difficult conversations that surround end-of-life decisions,” Washington continued. “Organizations such as skilled nursing facilities, medical schools, hospice and home care agencies, and assisted-living providers use Embodied Labs to improve outcomes, operations, and culture.”

In addition to creating its experiences, Embodied Labs creates customized assessment questions to be answered before and after staff and students sample a VR scenario. This qualitative and quantitative data can then be used to provide new insights, on the part of professionals, into things such as how conversations about end-of-life are carried out.

Building empathy

But does this actually work, or is this a case of creating a solution to a problem that doesn’t actually exist? In fact, according to a new piece of research, virtual reality really be prove to be a useful tool in encouraging empathy.

In a study published this month in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, researchers from Stanford University compared the attitudes of people who had read a first-person narrative piece of writing about homelessness, those who had experienced a 2D interactive narrative about it on computer, and those who had undergone a perspective-taking VR scenario on the same topic. They found that the people who had experienced the VR simulation were more likely to sign a petition to support homeless populations. Follow-up surveys also found that they experienced longer-lasting empathetic feelings than those who had done the narrative-reading task.

Of course, there are problematic aspects with the idea of building empathy through VR. A 30-minute simulation about end-of-life conversations is not the same thing as experiencing it for real. A person really experiencing the effects of homelessness or discriminatory activity cannot simply take off their headset when they decide they’ve had enough of their life circumstances. Attempts to “gamify” complex scenarios risk inadvertently diminishing them, and carry the chance of turning something intended for good into something exploitative.

Of course, there are problematic aspects with the idea of building empathy through VR. A 30-minute simulation about end-of-life conversations is not the same thing as experiencing it for real. A person really experiencing the effects of homelessness or discriminatory activity cannot simply take off their headset when they decide they’ve had enough of their life circumstances. Attempts to “gamify” complex scenarios risk inadvertently diminishing them, and carry the chance of turning something intended for good into something exploitative.

However, properly considered, there is room for virtual reality as a teaching tool. Certainly, it needs the proper care and attention of trained professionals, and it shouldn’t be considered a substitute for other forms of teaching. But as something that we’re glad to see being explored? Absolutely. And if it potentially means more empathetic treatment for yourself and your fellow human beings, you should be, too.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Gilbert reflects on the death of her partner, Rayya Elias — her longtime best friend, whose sudden terminal cancer diagnosis unlatched a trapdoor, as Gilbert put it, into the realization that Rayya was the love of her life:

Gilbert reflects on the death of her partner, Rayya Elias — her longtime best friend, whose sudden terminal cancer diagnosis unlatched a trapdoor, as Gilbert put it, into the realization that Rayya was the love of her life: