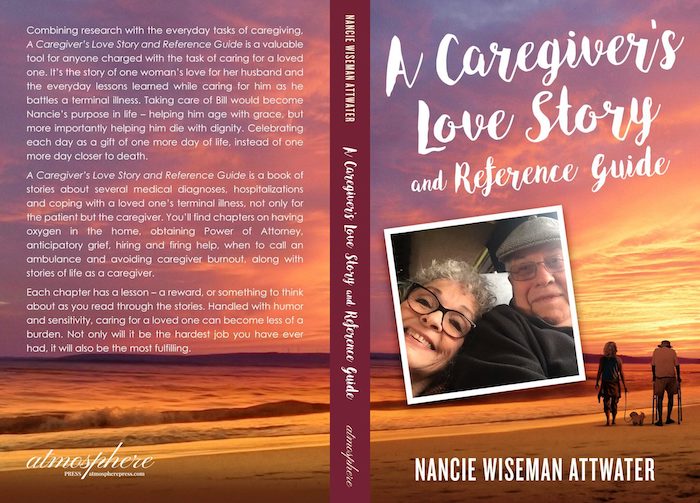

— “You may have feelings of dread, guilt, hopelessness, despair and overwhelm”

By Hannah Millington

We’re slowly starting to talk about grief more, partly due to the pandemic and partly thanks to evolving attitudes around sharing our experiences with mental health, in all its forms. But the term ‘anticipatory grief’ might possibly still be a new one for you – even if it’s likely that you personally, or someone you know, has experienced it.

While anticipatory grief – which focuses on our feelings before a grief-inducing loss, rather than just after – can be challenging and exhausting, there are ways to cope and support services out there.

But, before we dig deeper with the help of two trusted experts, we want to acknowledge off the bat that grief looks – and feels – different for everyone, and there is no such thing as experiencing it the ‘right way’. And the same goes for anticipatory grief, too.

So, what is anticipatory grief? What are the signs of it, and how can you put coping mechanisms in place? We asked the experts…

What is anticipatory grief?

“Anticipatory grief is the grief felt before an impending loss, typically someone dying,” says registered member of the British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy (BACP), counsellor Lisa Spitz.

However, Spitz explains that this ‘impending loss’ can also apply to non-death related situations, like divorce, or the scheduled removal of a limb or breast due to health reasons. The defining factor is that it is a big loss of some sort, that you anticipate will happen and that will drastically change your life.

In some cases, anticipatory grief can begin years before the loss occurs (though it may also just be a matter of days beforehand).

“It could be someone living with a dying spouse,” says the expert. “You may have feelings of dread, guilt, hopelessness, despair and overwhelm. It can include wondering and, in some cases, planning what life would or could look like afterwards [once they’ve passed].” All of which can be really tough to process on an emotional and practical level.

What are the signs of anticipatory grief?

In a nutshell: anticipatory grief is a term for the feelings that occur before a sizeable loss, which can range from dread to anxiety to despair, and can also be accompanied by physical elements, such as trouble sleeping, loss of appetite or feeling like you have a racing heart. It’s similar to grief itself, in that there are a myriad of ways it can present itself – and like each loss, each person experiencing it will do so in a unique way.

Expanding on the above, Spitz explains that in the case of losing a loved one that “there is often an overwhelming and sometimes paralysing concern for the dying person, a constant running order of how the death might look and plans to be made, as well as an attempt to adjust to life without them. It can feel overwhelming, exhausting and anxiety-provoking.”

It seems uncertainty is a big part of what can make anticipatory grief so taxing, and being unable to know for sure how your future might look.

If you’re experiencing feelings of anticipatory grief, one helpful first step can be simply acknowledging those emotions – and actively choosing to go a little easier on yourself: you’re not just ‘waiting’ or ‘preparing’ to go through a tough time, knowing that one is on the horizon is tough in itself too, and you deserve support now (and later down the line, once the loss has happened).

Why does anticipatory grief happen and do people’s experiences differ?

Much like grief itself, while anticipatory grief is a natural part of loss, there’s no one set way that it plays out, or one particular way that it looks.

As Jane Murray, counsellor and Bereavement Services lead for Marie Curie, Midlands, explains, “Very often relatives and carers have a feeling of helplessness or lack of control – particularly as the dying phase approaches – as there is nothing they can do to ‘stop’ the dying and all the decision-making is being done by the professionals. They then often feel increased anxiety and stress as they witness the actual dying.”

She adds that tensions can also be high when someone is dying, and it can place a lot of pressure on someone to say goodbye in the ‘best’ way possible, when they’re already dealing with so much.

“Some people may also feel judged by others in that they are not at the bedside often enough, or crying enough, or doing enough. They may feel guilty for taking a break or time out,” adds Murray. “This can cause an enormous amount of pressure which increases anxiety and stress. Just like a pressure cooker, that stress which is building has to be released or it may explode into anger or emotional outbursts.”

>With that in mind, we should feel entitled to reduce the pressure on ourselves to be ‘perfect’ when caring for or visiting a dying relative, who also may not be their usual selves.

“Guilt is a huge part of grief and because people are emotionally and physically exhausted, they can also expect to be short-tempered and emotional. All these feelings and behaviours are ‘normal’ at this time,” stresses Murray. “There really is no perfect way to react at such a time – there is only your own unique way. Normalising feelings and behaviours goes a long way to relieving anxiety at this time.”

These feelings can vary greatly, and might not always be ones of obvious compassion, which is okay. “Anger is also a big part of grief and to be expected – anger at the professionals for not doing a better job or curing the patient; anger at family and friends for not being there enough or being supportive enough; anger at themselves for not being ‘a good enough wife/daughter/son’.”

“Although seldom admitted, there can be anger at the patient themselves for dying and leaving them alone. Just like all the other emotions at this time anger should not be discouraged, it needs to be expressed in a safe way.”<

Other experts also highlight that anticipatory grief might be a positive, in its own strange way. “It allows some people to access the grieving process before it happens and potentially allow them to feel more prepared,” says Spitz. “Long illnesses often allow for time to say ‘goodbye’ and have that acknowledged.”

What are the different stages of anticipatory grief?

“Clients I encounter in my practice, often believe you must go through the stages (like denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance) in order to grieve ‘properly’ but this is untrue,” says Spitz. “You may go through multiple stages, or none at all. It is not linear and ‘stages’ may be revisited more than once and that’s also okay.

“We need to normalise that grief – to quote the late Queen Elizabeth – is the ‘price we pay for love’, and instead of expecting people to be over their grief [by a certain date], we should acknowledge that it becomes something we live with, a part of our fabric. We will always grieve but the goal is that it becomes less raw and overwhelming.”

So, with that in mind, it may prove useful to approach anticipatory grief by keeping in mind the types of feelings you may experience (dread, guilt, hopelessness, despair, overwhelm, anxiety, preparing, taking control, saying goodbye, etc), rather than anticipate any set order that they might arise in. Feelings can also repeat, even once you felt you’d ‘dealt’ with them.

How does anticipatory grief affect our experience of grief itself?

It’s likely that for most people anticipatory grief will be followed by grief (though not always, loved ones could make an unexpected recovery, for example). So for those who’ve had the chance to prepare, or expect the loss, what difference does this make to our processing?

“I think that this is an interesting question,” admits Spitz. “It’s almost like if we grieve before, can we not grieve when the person dies or the divorce happens or the breast is lost? The truth is they are different. I believe that if you have the opportunity to say goodbye to a dying loved one and they have been ill for a long time then it is a very different experience to a sudden death. The same is true to a relationship that you can see is ending, as opposed to your spouse one day saying it’s over. Or breasts removed because they are diseased and can be lifesaving.

“You can process so much but actual grief can only happen when the ending, whatever that is, has happened. You can believe and plan to think/feel one thing but actually feel something else completely (when it comes to it).”

How can you cope with anticipatory grief?

Anticipatory grief can go on for a while, or possibly have some back and forth – for those dealing with changing situations. But whether you experience it for five days or five years, support is out there.

Reach out for help

Be it with emotional or practical support (e.g. if you’re caring for an ill loved one, is someone else able to assist you with household chores for a bit? Can a charity, like Marie Curie, support with some counselling? Is there a local or online support group for others preparing to mourn the loss of a body part?).

Writing down feelings

“Journaling also helps,” says Spitz. “By externalising our internal thoughts and fears it helps to acknowledge and work through some of them.”

Practice self-care

If you’re looking after a dying loved one, this can also take its own toll. “For care givers, their own mental and physical health can suffer and looking after themselves is no longer a priority, adding to the feelings of overwhelm,” says Spitz. This makes it even more important to seek professional help or vocalise your feelings and needs to those who can listen.

Know that however you feel, it’s ‘normal’

In addition to urging us to take the pressure of ourselves to be ‘perfect’ during this time, and accept all the emotions that come our way, Murray adds: “Grief is very individual to the person – no two people will grieve the same even in the same family. There is no right way to grieve, your grief is unique to you.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!