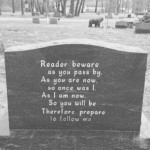

“We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Sahara. Certainly those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively outnumbers the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here.”

— Richard Dawkins

It might be odd to start a column about spirituality at the end of life with a quote from Richard Dawkins the noted atheist, but I believe there are plenty of spiritualties that don’t involve organized religion or even a divine being per se. So maybe he’s not as far off the mark as some traditionalists think.

I’ve been thinking a lot about metaphysics lately, because there have been several articles in the press lately that discuss the clinical efficacy of prayer in medical settings. Curiously enough, most researchers in this area of study will admit that it is very difficult to measure such things, but apparently antidotal evidence abounds and thus the continued interest.

For example, in one study sited by a doctor in her recent Boston Globe article, strangers were instructed to pray for patients undergoing heart surgery. The prayers did not seem to improve the patients’ outcomes. In fact, the study goes on to say, if the patients were told they were being prayed for, they had more postoperative complications. But for every study that finds a dubious connection between prayer and its effectiveness there is another study that suggests just the opposite—prayer as being powerful and transformative.

So I got to thinking; maybe it’s not so much if people pray, but rather what people pray. And maybe, just maybe, it is what we pray for, if we pray at all, that might be the determining factor in whether or not our prayers are answered or even perceived to be answered.

What I know for certain is, much of what passes for spirituality, particularly at the end of life, is fear based—dealing with divine retribution. It never ceases to amaze me that people continue to pray to a God that is abusive. Isn’t that like paying someone to beat you?

Many people embrace a spiritual path that teaches that there is merit in suffering. This, they believe, is a way of atoning for one’s sins. (I’ve always thought that such a philosophy was a no brainer since life is full of suffering and we humans are such flawed creatures.) But if there is virtue in suffering, how can suffering that makes us bitter and angry and at odds with our self and our God be the source of merit?

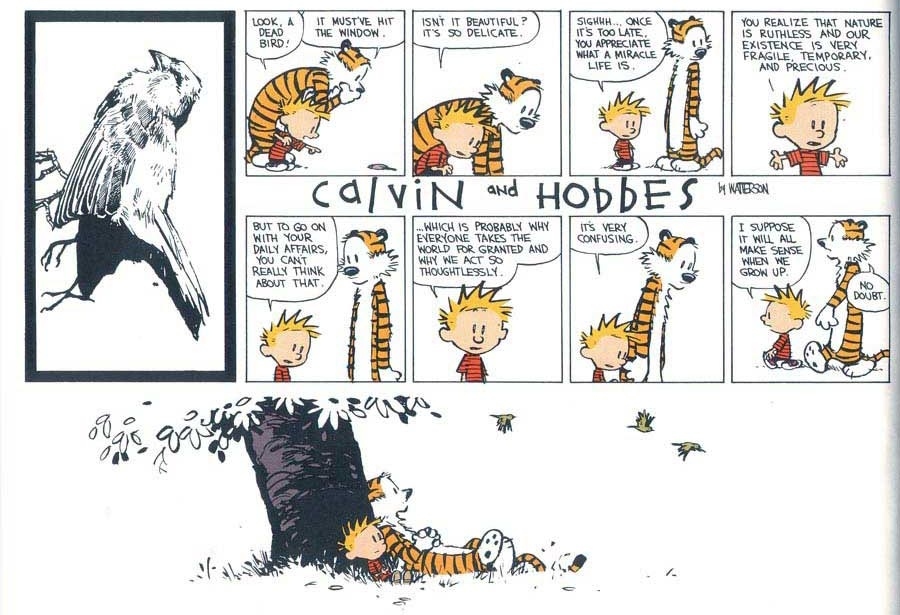

I reminded of the groundbreaking work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. Her five stages of grief — denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance has a lot to do with spirituality, and not always in a good way. For example, consider the bargaining stage. Traditionally this stage involves attempting to bargain with God to miraculously change the course of one’s life—I was dying, but now I’m not.

If one prays for deliverance—that this cancer be cured or this terminal diagnosis be reversed—perhaps the prayer will seem to go unanswered, because we are all mortal. But if the prayer is for serenity, under these same trying circumstances, perhaps that prayer will be answered, because serenity is easier to come by than a cure.

In the end, I think Professor Dawkins is right; we are lucky. Our existence, be it a quirk of cosmic fate or personally designed by the hand of God, makes us special. And regardless if we thank our lucky stars, or thank divine providence, our prayer of thanksgiving will always be answered, because, simply put, giving thanks is its own reward.