Breaking the silence: are we getting better at talking about death?

As the media brings us constant news of strangers’ deaths, grief memoirs fill our shelves and dramatic meditations are performed to big crowds, we have reached a new understanding of mortality, says Edmund de Waal

[B]ereavement is ragged. The papers are full of a child’s last months, the protests outside hospitals, the press conferences, court cases, international entreaties, the noise of vituperation and outrage at the end of a life. A memorial after a violent death is put up on a suburban fence. It is torn down, then restored. This funeral in south London becomes spectacle: the cortege goes round and round the streets. The mourners throw eggs at the press. On the radio a grieving mother talks of the death of her young son, pleading for an end to violence. This is the death that will make a difference. She is speaking to her son, speaking for her son. Her words slip between the tenses.

Having spent the last nine months reading books submitted for the Wellcome book prize, celebrating writing on medicine, health and “what it is to be human”, it has become clear to me that we are living through an extraordinary moment where we are much possessed by death. Death is the most private and personal of our acts, our own solitariness is total at the moment of departure. But the ways in which we talk about death, the registers of our expressions of grief or our silences about the process of dying are part of a complex public space.

Some are explorations of the rituals of mourning, how an amplification of loss in the company of others – the connection to others’ grief – can allow a voicing of what you might not be able to voice yourself. The actor and writer Natasha Gordon’s play about her familial Jamaican extended wake, Nine Night, is coming to the end of a successful run at the National Theatre. The nine nights of the wake are a theatre of remembrance, a highly codified period of time shaped to allow the deceased to leave the family.

Julia Samuel records in Grief Works, her remarkable book of stories of bereavement, a woman who “asked friends and family to sit shiva [the Jewish mourning tradition] with me at a certain time and place”. And that there was anguish when these particular times were ignored: two friends came at times that were “convenient for them rather than when she was sitting shiva, thus ‘raising all the issues I was temporarily trying to keep contained’”.

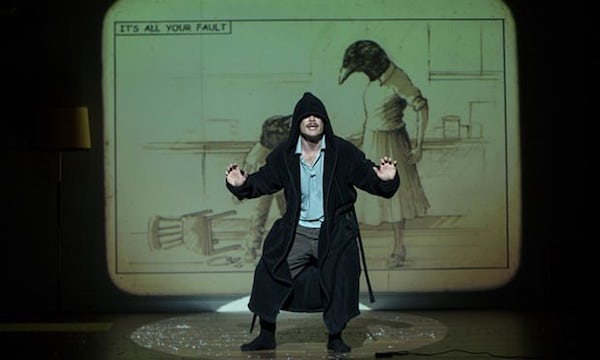

As an academic writes in the accompanying notes to artist Taryn Simon’s performance An Occupation of Loss, recently staged in London, “communication between the living and the dead is possible only in mediated forms”. There are obligations we have to fulfil to those who have died. Simon gathered professional mourners from 15 countries (Ghana, Cambodia, Armenia and Ecuador, among others). The mourners wailed and sobbed and keened, the intensity of their expression, their sheer volume, a challenge to the idea that there has to be a silence that surrounds bereavement.

There are silences. Contemporary books on death often take as their premise that to be writing in the first place is a breaking of a taboo. “It’s time to talk about dying,” writes Kathryn Mannix in her book about her work in palliative care, With the End in Mind. “There are only two days with fewer than 24 hours in each lifetime, sitting like bookmarks astride our lives: one is celebrated every year, yet it is the other that makes us see living as precious.” These books record the silence that we in the west have created. By removing dying into a medical context, where expertise and knowledge lie so emphatically with others, we have made death unusual, a process clouded by incomprehension. And by novelty.

So one kind of language we need is that of clarity. A lucidity that allows for the involvement of family and friends alongside healthcare professionals. Clarity, writes Mannix, around the questions such as “when does a treatment that was begun to save a life become an interference that is simply prolonging death? People who are found to be dying despite the best efforts of a hospital admission can only express a choice if the hospital is clear about their outlook.” Conversations about palliative care need extraordinary skill and empathy. These are skills that can be learned.

But for someone writing about their own grief, there are no guidelines. You might have read Thomas Browne’s Urn Burial, or the poems of John Donne, the theories of John Bowlby or Donald Winnicott, Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia, but it simply doesn’t register. Being well read doesn’t help when someone who matters dies. Part of this attempt to start again, to find a form out of the formlessness of grief, is a reluctance to take on the generic language of sympathy, the homogeneous effect of cliche. Bereavement is bereavement, not a masterclass in being well read in the classics. “The death of a loved one is also the death of a private, whole, personal and unique culture, with its own special language and its own secret, and it will never be again, nor will there be another like it,” writes David Grossman in Falling Out of Time, his novel about the death of his son. A death needs a special language.

The language of loss and the framing of sympathy in everyday life is so impoverished, so mired in cliche and euphemism, that deep metaphors of “passing” become thinned to nothing, to sentimentality. The iterations of “losing the battle” and the valorising, endlessly, of “courage” is a way of making the bereaved feel they need to enact a particular role. And then there is the “being strong”. If you are told how wonderful you are for not showing emotion, or for continuing as before, where does that leave being scared? How about denial? Or anger, terror, desolation, loneliness? How about confusion? Why only endurance, resilience, strength? In this need to name, to find precision, accuracy is a measure of love. I think of Marion Coutts’ book The Iceberg, on her dying husband Tom Lubbock’s language, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, charting everything, weighing her responses to her grief. This is different, they say, writing this is a work of mourning.

The greatest of these books find a language that encompasses the sheer confusion of bereavement. In her forthcoming book Everyday Madness: On Grief, Anger, Loss and Love, Lisa Appignanesi writes that “Death, like desire, tears you out of your recognisable self. It tears you apart. That you was all mixed up with the other. And both of you have disappeared. The I who speaks, like the I who tells this story, is no longer reliable.” This is the other loss, that of selfhood, of control, of a forward momentum, of certainty. Appignanesi’s grief at the untimeliness of her husband’s death makes time itself deranged. Her days and weeks and months go awry. Her sense of the past is also called into question. It is excoriating: “My lived past, which had been lived as a double act, had been ransacked, stolen.” Bereavement, she notes, has a deep etymology of plunder. It tears you apart. Where all these registers go wrong, you oscillate between kinds of behaviour that are disinhibited, a derangement of self. It can be physical, a falling, a losing your way. I think of the crow in Max Porter’s Grief Is the Thing with Feathers as the deranged, ransacking presence in a family where the mother has died.

These are images that go deep into history. In the Book of Lamentations we read that God “has made me dwell in darkness … he has walled me in and I cannot break out … He has weighed me down with chains … He has made my path a maze … He has forced me off my way and mangled me.” The Hebrew word eikh (how) opens the Book of Lamentations and then reappears throughout the text. This how is not a question, more a bewildered exhortation. You are beyond questions. All you can do is repeat.

In Anne Carson’s poem Nox, a response to the death of her brother, she refused to accept any conventional form. So the poem comes like a box, a casket, of fragments, attempts at definitions, parts of memories. This seems appropriate. The shape of grief is different each time. That is why the shard – the pieces of broken pottery that are ubiquitous across all cultures – is often used as an expressive image of loss. Think of Job lamenting to God, sitting on a pile of broken shards. In my own practice as a potter, whenever I pick up pieces of a dropped vessel I notice that each shard has its own particularity. Each hurts.

In her study of the deaths of writers, The Violet Hour, Katie Roiphe writes that “moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project. I refuse to rush. The pain that is thrust upon us let no man slow or speed or fix.” Bereavement takes a pathway that is different for each and every one of us. It takes different registers, different words. And that is what I take away from this very particular nine months of reading and reflecting on mortality. That there is change in the public space around death. This change is remarkable and wonderful when it comes to end-of-life care: the hospice movement and the training in palliative care are one of the greatest and most compassionate changes to occur in the last 30 years.

And, more slowly, it is happening outside the hospitals and clinics and hospices. People do want to read and talk about grief. For this we have to be grateful to those writers who are trying to find their own shard-like languages to express their own bereavements.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

When someone hovers at the edge of death, these singers step in to ease the passage

by Debra Bruno

[I]t’s a quiet afternoon at the Halquist Memorial Inpatient Center, a hospice, as four women huddle close, talking quietly in a tight circle before walking through the doors to sing to men and women on the threshold of death.

These women are part of the Threshold Choir, a group that brings the comfort of song to dying people.

A thin woman, who is in the last weeks of life, is the choir’s first stop. She is sitting nearly upright in a hospital bed, her daughter beside her. Leslie Kostrich, the group’s leader for this day, asks the older woman if she would like to hear a few songs. She nods; the singers set up folding stools and pull up close to her bed.

“We sing in a circle of love,” the women sing, a cappella and in three-part harmony. “In music we are joined.” As they sing, the woman gazes off with a faraway look in her eyes, as if she’s trying to remember something.

The group sings another song, and as they finish, the older woman claps softly. “Thank you,” she says. “Nice.”

It takes sensitivity, situational awareness and a dash of emotional intelligence to sing to the dying. The sound of soft harmonious voices can be very comforting as life closes down, but the songs can also bring forward the immediacy of death to family members sitting nearby. Singing in such an emotional environment takes practice and a recognition that it is less a performance than a service.

For the dying and their families, the singers are hoping to bring peace, comfort and a feeling of love. “We call it kindness made audible,” says Jan Booth, who with Kostrich is co-director of the Washington-area Threshold group.

It is also very life-affirming for those who sing in this unusual choir.

“When I tell people I’m in a choir that sings at the bedside of the dying, they’ll say, ‘Oh girl, what a good thing,’ or ‘Girl, you must have lost your mind,’ ” says Kadija Ash, 66.

But the opposite is true. “Sometimes I run” to rehearsals, she says, “because of the healing.” In the two years she has been a member of Threshold, Ash says, she has gone from having a fear of death to an ability to be more accepting of life’s ups and downs.

Kostrich, 60, who has been with the group for three years, likewise says: “This has changed my life. That’s not an exaggeration. It gave my life a spiritual dimension that I was totally unprepared to receive.”

Threshold Choir — which has more than 200 groups around the world — seems to have tapped into something both primal and much-needed: a growing desire not to recoil from death or abandon the dying but to face that ultimate truth and figure out how to help ease the isolation of those near the end.

Bedside singing is a way of “normalizing death,” says Kate Munger, 68, who founded the first group in the San Francisco area 18 years ago. Many of the choirs are started and run by baby boomers, who are comfortable shaking up the accepted way of doing things, Munger says. “We’ve done that for childbirth, for education, and now for our impending death.” She says the number of people participating in Threshold Choir has grown to about 2,000.

Similar deathbed choirs have also surged, including Hallowell Singers, based in Vermont, which recently celebrated its 15th year, says founder Kathy Leo. She estimates that Hallowell has as many as 100 spinoffs, mainly in the United States.

Although they sing some requested songs, such as “Amazing Grace,” Threshold Choir mostly uses a repertoire designed for singing around a dying person. The pieces tend to be limited to just a few words, and sung without accompaniment in three-part harmony.

The idea is to keep things simple and not tied to any spiritual tradition — for instance, “Thank you for your love” and “We are all just walking each other home.” Complicated verses could intrude on the process of dying, which often involves people retreating from the day-to-day and reviewing their lives.

During the afternoon at Halquist, the four Threshold singers — Booth, Kostrich, Ash and Margo Silberstein — move out into a hallway after their first group of songs. One hospice staffer says, “I love working on Thursdays because I love listening to this group.”

The group slips into another large room with four beds separated by curtains. A frail woman with brilliant blue eyes smiles at the group. In another bed, someone is making noises that are halfway between breathing and groaning.

The blue-eyed woman asks, “Do you know ‘A Mighty Fortress?’ ” The group knows some of the words to the hymn but ends up mostly singing “oooo” to its tune. After they finish, Kostrich offers, “We do have ‘Amazing Grace.’ ” “Oh yes,” the woman answers and quietly sings along with them. After they finish, she says: “Oh, thank you. That was just wonderful.” They go on to sing “Simple Gifts” and “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” and then a few Threshold songs.

A TV next to a different bed blares.

After they finish, they approach a man sitting at the bedside of a woman. Can they sing?

“She’s pretty well gone out, but you can try,” he says.

As they sing “Hold this family in your heart,” the man’s eyes redden. He shifts in his seat. They sing, “Rest easy, let every trouble drift away.” His chin starts to tremble. As they begin to sing “You are not alone,” the woman begins to breathe more loudly but doesn’t move. The woman in the bed across the room, where they first sang, calls out, “Beautiful!”

An hour later, as the group gets ready to leave the hospice, Kostrich says that singing with Threshold has given her a way to process her own family’s experiences with death. When her parents were dying in the 1980s, Kostrich says, no one acknowledged they were close to death, which didn’t allow her and her family to come to terms with the losses themselves. The Threshold Choir has both helped her in a small way alleviate her own loss and help others avoid that kind of pain, she says.

There’s another thing that comes out of Threshold singing: community. And that feeling is evident when group members get together for a twice-a-month rehearsal, often in a church basement in the District. All but one singer at this rehearsal is female, but they range in age from 20-somethings to 70-somethings, African American, Chinese and white, those with tattoos and those with carefully coifed hairdos. There are a lot of hugs and laughter.

Olivia Mellon Shapiro, 71, says that group members are her “kindred spirits.” When she retired from her work as a psychotherapist, she told a friend, “Now I want to sing people out in hospices,” Shapiro says. “My father sang himself out — he died singing, and I was very moved by that.” Her friend said, “Oh, that’s the Threshold Choir.”

“Now I have a new group that feels like home to me. It really does,” she says. “I’ve also always been a little afraid of death and dying, but I’ve always loved the idea of hospices. So the idea of singing people out in hospices to get more comfortable with the idea of death and dying appealed to me.”

(The group sings several times a month at Halquist in Arlington and also at Providence Hospital in Northeast D.C. through the nonprofit hospice provider Capital Caring.)

One of the singers, Lily Chang, 28, notes that the choir is helping her confront her own fears of loss.

Chang says she’s very close to her grandmother and, given her age, worries about her. “I remember telling my mom, ‘I don’t know what I would do’ ” if she died. “Thinking about it, engaging with it in different ways makes me feel better.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How dying offers us a chance to live the fullest life

The price of a humanity that actually grows and changes is death.

[P]eople still sometimes discuss the question of how you could tell that you were talking to some form of artificial intelligence rather than an actual human being. One of the more persuasive suggested answers is: “Ask them how they feel about dying.” Acknowledging that our lifespan is limited and coming to terms with this are near the heart of anything we could recognise as what it means to be human.

Once we discovered that Neanderthals buried their dead with some ritual formality, we began to rethink our traditional species snobbery about them and to wonder whether the self-evident superiority of homo sapiens was as self-evident as all that. Thinking about dying, imagining dying and reimagining living in the light of it, this is – just as much as thinking about eating, sex or parenting – inseparable from thinking about our material nature – that to have a point of view at all we have to have a physical point of view, formed by physical history. Even religious systems for which there is a transition after death to another kind of life will take for granted that whatever lies ahead is in some way conditioned by this particular lifespan.

Conversely, what the great psychoanalytic thinker Ernest Becker called “the denial of death” is near the heart of both individual and collective disorders: the fantasy that we can as individuals halt the passage of time and change, and the illusions we cherish that the human race can somehow behave as though it were not in fact embedded in the material world and could secure a place beyond its constraints. Personal neurosis and collective ecological disaster are the manifest effects of this sort of denial. And the more sophisticated we become in handling our environment and creating virtual worlds to inhabit and control, the looser our grip becomes on the inexorable continuity between our own organic existence and the rest of the world we live in.

It’s a slightly tired commonplace that we moderns are as prudish in speaking about death as our ancestors were in speaking about sex. But the analogy is a bit faulty: it’s not simply that we are embarrassed to talk about dying (although we usually are), more that we are increasingly lured away from recognising what it is to live as physical beings. As Kathryn Mannix bluntly declares at the beginning of her book about pallia-tive care, “It’s time to talk about dying”. That is if we’re not to be trapped by a new set of superstitions and mythologies a good deal more destructive than some of the older ones.

Each of these books in its way rubs our noses in physicality. Caitlin Doughty’s lively (and charmingly illustrated) cascade of anecdotes about how various cultures handle death spells out how contemporary Western fastidiousness about dead bodies is by no means universally shared. We are introduced to a variety of startling practices – living with a dead body in the house, stripping flesh from a relative’s corpse, exhuming a body to be photographed arm in arm with it… all these and more are routine in parts of the world. And pervading the book is Doughty’s ferocious critique of the industrialisation of death and burial that is standard in the United States and spreading rapidly elsewhere.

Doughty invites us to look at and contemplate alternatives, including the (very fully described) composting of dead bodies, or open-air cremations. A panicky urge to get bodies out of the way as dirty, contaminated and contaminating things has licensed the development of a system that insists on handing over the entire business of post-mortem ritual to costly and depersonalising processes that are both psychologically and environmentally damaging (cremation requires high levels of energy resource, and releases alarming quantities of greenhouse gases; embalming fluid in buried bodies is toxic to soil). Doughty has pioneered alternatives in the US, and her book should give some impetus to the growing movement for “woodland burial” in the UK and elsewhere. At the very least, it insists that we have choices beyond the conventional; we can think about how we want our dead bodies to be treated as part of a natural physical cycle rather than being transformed into long-term pollutants, as lethal as plastic bags.

Talking about choices and the reclaiming of death from anxious professionals takes us to Kathryn Mannix’s extraordinary and profoundly moving book. Mannix writes out of many years’ experience of end-of-life care and presents a series of simply-told stories of how good palliative medicine offers terminally ill patients the chance of recovering some agency in their dying. Those who are approaching death need to know what is likely to happen, how their pain can be controlled, what they might need to do to mend their relationships and shape their legacy. And, not least, they need to know that they can trust the medical professionals around to treat them with dignity and patience.

Mannix’s stories are told with piercing simplicity: and there is no attempt to homogenise, to iron out difficulties or even failures. A recurrent theme is the sheer lack of knowledge about dying that is common to most of us – especially that majority of us who have not been present at a death. Mannix repeatedly reminds us of what death generally looks like at the end of a degenerative disease, carefully underlining that we should not assume it will be agonising or humiliating: again and again, we see her explaining to patients that they can learn to cope with their fear (she is a qualified cognitive behavioural therapist as well as a medical professional). It is not often that a book commends itself because you sense quite simply that the writer is a good person; this is one such. Any reader will come away, I believe, with the wish that they will be cared for at the end by someone with Mannix’s imaginative sympathy and matter-of-fact generosity of perception.

Sue Black’s memoir is almost as moving, and has something of the same quality of introducing us to a few plain facts about organic life and its limits. She moves skilfully from a crisp discussion of what makes us biologically recognisable as individuals and how the processes of physical growth and decay work to an account of her experience as a forensic anthropologist, dedicated to restoring and making sense of bodies whose lives have ended in trauma or atrocity. The most harrowing chapter (and a lot of the book is not for those with weak stomachs) describes her investigations at the scene of a massacre in Kosovo: it is a model of how to write about the effect of human evil without losing either objectivity or sensitivity.

Perhaps what many readers will remember most vividly is her account of her first experience of working as a student with a cadaver. For all the stereotypes of the pitch-dark and tasteless humour of medical students in this situation, the truth seems to be that a great number of them actually develop a sense of relatedness and indebtedness to the cadavers they learn on and from. Black writes powerfully about the sense of absorbing wonder, as the study of anatomy unfolds, of the way in which it reinforces an awareness of human dignity and solidarity – and of feeling “proud” of her cadaver and of her relation with it.

For what it’s worth, having taken part in several services for relatives of those who have donated their bodies to teaching and research, I can say that the overwhelming feeling on these occasions has been what Black articulates: a moving mutual gratitude and respect. And the book is pervaded by the sense of fascinated awe at both the human organism and the human self that comes to birth for her in the dissecting room.

Richard Holloway writes not as a medical professional but as a former bishop, now standing – not too uneasily – half in and half out of traditional Christian belief, reflecting on his own mortality and the meaning of a life lived within non-negotiable limits. His leisurely but shrewd prose – with an assortment of poetic quotation thrown in – is a good pendant to the closer focus of the other books, and he echoes some of their insights from a very different perspective. Medicine needs to be very wary indeed of obsessive triumphalism (the not uncommon attitude of seeing a patient’s death as a humiliation for the medical professional); the imminence of death should make us think harder about the possibility and priority of mending relations; the fantasy of everlasting physical life is just that – not a hopeful prospect, but the very opposite.

He has some crucial things to say about the politics of the drive towards cryogenic preservation. Even if it were possible (unlikely but at best an open question) it is something that will never be available to any beyond an elite; any recovered or reanimated life would be divorced from the actual conditions that once made this life, my life, worth living; how would a limited physical environment cope with significant numbers of resuscitated dead? The book deserves reading for these thoughts alone, a tough-minded analysis of yet another characteristic dream of the feverish late-capitalist individual, trapped in a self-referential account of what selfhood actually is.

****

Odd as it may sound, these books are heartening and anything but morbid. Mannix’s narratives above all show what remarkable qualities can be kindled in human interaction in the face of death; and they leave you thinking about what kind of human qualities you value, what kinds of people you actually want to be with. The answer these writers encourage is “mortal people”, people who are not afraid or ashamed of their bodies, those bundles of rather unlikely material somehow galvanised into action for a fixed period, and wearing out under the stress of such a rich variety of encounter and exchange with

the environment.

None of these books addresses at any great length the issues of euthanasia and assisted dying, but the problem is flagged: Black says briskly that she hopes for a change in the law (but is disarmingly hesitant when it comes to particular cases), while Mannix, like a large number of palliative care professionals, strikes a cautionary note. She tells the story of a patient who left the Netherlands for the UK because he had become afraid of revealing his symptoms fully after being (with great pastoral sensitivity and kindness) encouraged by a succession of doctors to consider ending his life. “Be careful what you wish for,” is Mannix’s advice; and she is helpfully clear that there are real options about the ending of life that fall well short of physician-assisted suicide.

Like all these authors, she warns against both the alarmist assumption that most of us will die in unmanageable pain and powerlessness and the medical amour propre that cannot discern when what is technically possible becomes morally and personally futile – when, that is, to allow patients to let go. The debate on assisted dying looks set to continue for a while yet; at least what we have here goes well beyond the crude slogans that have shadowed it, and Mannix’s book should lay to rest once and for all the silly notion occasionally heard that palliative care is a way of prolonging lives that should be economically or “mercifully” ended.

The most important contribution these books make is to keep us thinking about what exactly we believe to be central to our human condition. It is not a question to answer in terms simply of biological or neurological facts but one that should nag away at our imagination. How do we want to be? And if these writers are to be trusted, deciding that we want to be mortal is a way of deciding that we want to be in solidarity with one another and with our material world, rather than struggling for some sort of illusory release.

Richard Holloway doesn’t quite say it in these terms, but the problem of a humanity that doesn’t need to die is that it will be a humanity that needs no more births. The price of a humanity that actually grows and changes is death. The price of eternal life on earth is an eternal echo chamber. As someone once said around this time of year: “Unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed.”

Waiting for the Last Bus: Reflections on Life and Death

Richard Holloway

Canongate, 176pp

All that Remains: a Life in Death

Sue Black

Doubleday, 368pp

From Here to Eternity: Travelling the World to Find the Good Death

Caitlin Doughty

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 272pp

With the End in Mind: Dying, Death and Wisdom in an Age of Denial

Kathryn Mannix

William Collins, 352pp

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What a dying old woman taught me about love

[I] was a newly trained hospice volunteer, and E. was to be my first patient. I had to work up the nerve to cross the threshold.

After gently clearing my throat and shuffling my feet in an attempt to wake her, I bent low to look at her face. Suddenly, her eyes opened wide.

She was as startled as me and said, in a forced whisper, “Who are you?”

“I’ve come to visit for a while,” I replied.

“Why, are you being punished?” she deadpanned.

I laughed a little, mostly with relief. I introduced myself to the dying woman who was a few decades my senior and then nervously began a monologue, telling her all about me. She listened attentively for a while but soon closed her eyes. On a tray table was a wedding photo. I peered at the circa 1940s picture and was taken aback. “Wow!” I said out loud. In her youth, E. had been stunningly beautiful. Bright eyes, fresh face. I looked up and saw her once clear but now milky eyes examining my face, watching my reaction to the photo.

She was bedridden, her bones fragile. During our next visit, I asked the nurse if E. could go outside in a wheelchair. The nurse said it was up to E. We rolled out into the sunlight and fresh air, and that’s when everything began to move faster for us, literally and figuratively.

I maneuvered her down the cracked and bumpy sidewalk into a nearby neighborhood. She lifted her face to the sun and opened her mouth to its warmth. She stayed that way until I parked the chair under a shade tree. I sat down with the trunk as my backrest.

For the longest time, she simply stared at me. Until she slowly stretched out her arms and beckoned me to her. I jumped up, although she didn’t seem in distress. I leaned toward her and she gently cupped my face with her hands. I could feel the pressure of each finger on my face. Suddenly, with purpose, she pulled me close and kissed me. On the lips, with a dry pucker.

I was not made uncomfortable by the gesture. Quite the opposite. I sensed in her a genuine joy and appreciation. So she kissed me. Perhaps the most meaningful kiss of my life.

Those meetings under the tree became our routine, where we shared stories of our lives. We quickly bonded through unabashed, intimate conversations. I told her things about myself that I had never, nor would ever share with anyone else. We simply started talking to each other that way. Instant trust, instant karma. Instant honesty.

E. told me she wasn’t so much afraid of dying as she was of going to hell. She had married young, to a very ambitious man, and as the years progressed, his business flourished, but their marriage did not. He increasingly spent more and more time at the office, with colleagues and away from her. Estrangement set in.

She found a job as a secretary and over time fell prey to the attentions and intentions of her boss — afternoon “lunches” at a motel.

One day, on the ride back to the office, her boss spotted his wife in town, waiting to cross a street. With a violent shove, he sent E. into the passenger side footwell, hissing at her to stay down until he was sure he had avoided detection.

It was a humiliating and illuminating moment for E. She ended the affair. But the deed had been done. She was officially an adulterer. Worse, a mortal sinner. And now, as her life was about to end, she could not shake the guilt and dread that God was about to deliver her to the eternal fires of damnation.

She wept as I knelt beside her chair and held her.

I know something about the Catholic church, having been an altar boy. I reminded her about the convenience of confession. “From what I just saw, I’ll assume you are truly remorseful.” “Yes of course,” she said. “And you have formally confessed this, yes?” “Once a month for the past 66 years,” she said. “Well, then, I think God has gotten the message … you’re off the hook!” “Do you think so?” she asked earnestly. “I know so,” I told her.

As our visits continued, I also shared stories I was not proud of, of my regrets, sins, character flaws, abuse of drugs and alcohol, tales of ruined relationships and marriages and career paths gone awry. How I blamed others and circumstances as if the bad things that happened in my life were not of the choices I made. She was at times scandalized by what she heard, but never judgmental. The process was cathartic, cleansing, transformative.

I felt a lightness of being I had never experienced before.

Within a year, she began to rapidly decline. During the day, I’d find her in a deep sleep. The nurses said she’d lay awake most nights and was eating very little. I started setting my alarm for 1:30 a.m. to make the 40-minute drive to her facility in the San Fernando Valley. I’d sit on a folding chair and move in close, so our whispered conversations would not wake others.

She was comforted and calmed by my presence. She was grateful that I had re-arranged my visiting times. (I know because she told me so.) And she also told me that she loved me. Too weak now to even raise her hands to my face, I fulfilled the need for that contact by tenderly kissing her cheek and forehead often. I needed it too. Time was slipping away.

I soon realized her truth, raw honesty and tenderness had created in me a level of introspection and self-examination that had previously been inaccessible. Was this a cause and effect of true love? And I did grow to love her — for her courage, candor and kindness. She was well aware her days were numbered. But for all of her failing health issues, she never expressed bitterness. It was another lesson learned for me.

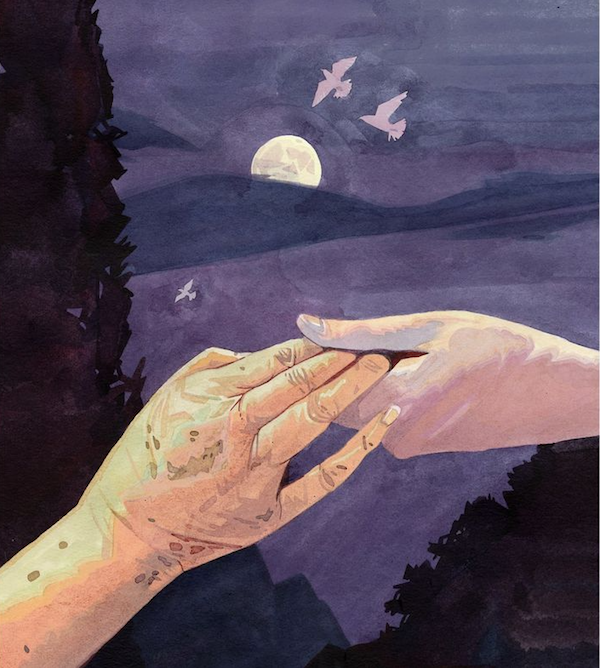

For the first time in almost two years after I started visiting with E., I was going to be away from her, to make good on a long-planned vacation in the Yucatán. I told her that I’d be gone only a week and during that time there would be a full moon. I suggested that since she was awake at night she should look up for the full moon, and I promised I would too, and maybe we’d do it at the same time. Corny, maybe, but she didn’t think so.

One night during the middle of my trip, I couldn’t sleep and walked outside to where a hammock was strung between two palm trees. I laid back and looked up at a crystal clear moon and said out loud, “See? I told you.”

Upon returning home, it took me a few days to get back into the groove of work and life. But before I could make my next visit, I got a call from the hospice volunteer coordinator. E. had died while I was away. Peacefully, in her sleep, at age 87.

I often think of E., of how a dying old woman helped me to access and express my true, honest feelings about life and love. Not only did I get to learn from my mistakes, but from hers, too. I was able to affect the quality of her life for a time, but not the direction. She did both for me.

In real ways, we set each other free.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

When do you know you’re old enough to die?

Barbara Ehrenreich has some answers

By Lucy Rock

With her latest book, Natural Causes, Barbara Ehrenreich notes that there’s an age at which death no longer requires much explanation

[F]our years ago, Barbara Ehrenreich, 76, reached the realisation that she was old enough to die. Not that the author, journalist and political activist was sick; she just didn’t want to spoil the time she had left undergoing myriad preventive medical tests or restricting her diet in pursuit of a longer life.

While she would seek help for an urgent health issue, she wouldn’t look for problems.

Now Ehrenreich felt free to enjoy herself. “I tend to worry that a lot of my friends who are my age don’t get to that point,” she tells the Guardian. “They’re frantically scrambling for new things that might prolong their lives.”

It is not a suicidal decision, she stresses. Ehrenreich has what she calls “a very keen bullshit detector” and she has done her research.

The results of this are detailed in her latest book, Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer, published on 10 April.

Part polemic, part autobiographical, Ehrenreich – who holds a PhD in cellular immunology – casts a skeptical, sometimes witty, and scientifically rigorous eye over the beliefs we hold that we think will give us longevity.

She targets the medical examinations, screenings and tests we’re subjected to in older age as well as the multibillion-dollar “wellness” industry, the cult of mindfulness and food fads.

These all give us the illusion that we are in control of our bodies. But in the latter part of the book, Ehrenreich argues this is not so. For example, she details how our immune systems can turn on us, promoting rather than preventing the spread of cancer cells.

When Ehrenreich talks of being old enough to die, she does not mean that each of us has an expiration date. It’s more that there’s an age at which death no longer requires much explanation.

“That thought had been forming in my mind for some time,” she says. “I really have no hard evidence about when exactly one gets old enough to die, but I notice in obituaries if the person is over 70 there’s not a big mystery, there’s no investigation called for. It’s usually not called tragic because we do die at some age. I found that rather refreshing.”

In 2000, Ehrenreich was diagnosed with breast cancer (she wrote the critical, award-winning essay Welcome to Cancerland about the pink ribbon culture).

The experience of cancer treatment helped shape her thoughts on ageing, she says.

“Within this last decade, I realised I was not going to go through chemotherapy again. That’s like a year out of your life when you consider the recovery time and everything. I don’t have a year to spare.”

In Natural Causes, Ehrenreich writes about how you receive more calls to screenings and tests in the US – including mammograms, colonoscopies and bone density scans – as you get older. She claims most “fail the evidence-based test” and are at best unnecessary and worst harmful.

Ehrenreich would rather relax with family and friends or take a long walk than sit in a doctor’s waiting room. She lives near her daughter in Alexandria, Virginia, and likes to pick up her 13-year-old granddaughter from school and “hang out with her a while”.

Work is still a passion too. She fizzes with ideas for articles and books on subjects that call for her non-conformist take.

Once a prominent figure in the Democratic Socialists of America, she is also busy with the Economic Hardship Reporting Project she founded, which promotes journalism about inequality and poverty in the US, and gives opportunity to journalists who are struggling financially. (The Guardian often partners with the organisation.)

Ehrenreich, who is divorced, has talked to her children – Rosa, a law professor, and Ben, a journalist and novelist – about her realisation she is old enough to die, but “not in a grim way”. That wouldn’t be her style. While a sombre subject, she chats about it with a matter-of-fact humour.

“I just said: ‘This is bullshit. I’m not going to go through this and that and the other. I’m not going to spend my time, which is very precious, being screened and probed and subjected to various kinds of machine surveillance.’ I think they’re with me. I raised them right,” she laughs.

“The last time I had to get a new primary care doctor I told her straight out: ‘I will come to you if I have a problem, but do not go looking for problems.’”

She pauses: “I think I beat her into submission.”

Natural Causes is Ehrenreich’s 23rd book in 50 years. Much of her work is myth-busting, such as Bright-sided, which looks at the false promises of positive thinking; other work highlights her keen sense of social justice. For her best-selling 2001 book Nickel and Dimed, she went undercover for three months, working in cleaning, waitressing and retail jobs to experience the difficulties of life on a minimum wage.

A recent exchange with a friend summed up what Ehrenreich hoped to achieve with Natural Causes.

“I gave the book to a dear friend of mine a week ago. She’s 86 and she’s a very distinguished social scientist and has had a tremendous career. “She said: ‘I love this, Barbara, it’s making me happy.’ I felt ‘wow’. I want people to read it and relax. I see so many people my age – and this has been going on for a while – who are obsessed, for example, with their diets.

“I’m sorry, I’m not going out of this life without butter on my bread. I’ve had so much grief from people about butter. The most important thing is that food tastes good enough to eat it. I like a glass of wine or a bloody mary, too.”

Yet despite her thoughts on the “wellness” industry with its expensive health clubs (fitness has become a middle-class signifier, she says) and corporate “wellness” programs (flabby employees are less likely to be promoted, she writes), Ehrenreich won’t be giving up the gym anytime soon. She works out most days because she enjoys cardio and weight training and “lots of stretching”, not because it might make her live longer.

“That is the one way in which I participated in the health craze that set in this country in the 70s,” she says. “I just discovered there was something missing in my life. I don’t understand the people who say, ‘I’m so relieved my workout is over, it was torture, but I did it.’ I’m not like that.”

In Natural Causes, Ehrenreich uses the latest biomedical research to challenge our assumption that we have agency over our bodies and minds. Microscopic cells called macrophages make their own “decisions”, and not always to our benefit – they can aid the growth of tumours and attack other cells, with life-threatening results.

“This was totally shocking to me,” she says. “My research in graduate school was on macrophages and they were heroes [responsible for removing cell corpses and trash – the “garbage collector” of the body]. About 10 years ago I read in Scientific American about the discovery that they enable tumour cells to metastasise. I felt like it was treason!”

She continues: “The really shocking thing is that they can do what they want to do. I kept coming across the phrase in the scientific literature ‘cellular decision-making’.”

This changed her whole sense of her body, she says.

“The old notion of the body was like communist dictatorship – every cell in it was obediently performing its function and in turn was getting nourished by the bloodstream and everything. But no, there are rebels – I mean, cancer is a cellular rebellion.”

Ehrenreich, an atheist, finds comfort in the idea that humans do not live alone in a lifeless universe where the natural world is devoid of agency (which she describes as the ability to initiate an action).

“When you think about some of these issues, like how a cell can make decisions, and a lot of other things I talk about in the book, like an electron deciding whether to go through this place in a grid or that place. When you see there’s agency even in the natural world. When you think about it all being sort of alive like that, it’s very different from dying if you think there’s nothing but your mind in the universe, or your mind and God’s mind.”

Death becomes less a terrifying leap into the abyss and more like an embrace of ongoing life, she believes.

“If you think of the whole thing as potentially thriving and jumping around and having agency at some level, it’s fine to die,” she adds reassuringly.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

There is more than one way to die with dignity

By I

“Who are you here to see?”

On this day, I was at Mount Sinai Hospital, in the oncology ward. The receptionist I usually check in with wasn’t at her desk. I was being greeted by a volunteer. Dark hair, wide eyes and a smile like a child’s doll. High school co-op student, maybe?

I handed over my health card and told her my doctor’s name.

“I’m sorry, I don’t know who she is. What are you here for?”

Her smile widens.

“Because I’m a patient?” I retort.

I know I’m being rude. But it’s an oncology ward. What does she think I’m here for? To discuss the weather? The shortage of wheelchair-accessible parking spaces in the lot?

What I really want to say is, my doctor is a palliative-care specialist. I’m seeing her because I have cancer. I’m preparing for my death.

I don’t look like I have cancer, let alone the incurable kind. I have all my hair. My friends and husband assure me my colour is good. Dressed in my normal clothes and not the pajamas I currently favour, I look reasonably well – for a middle-aged woman who also has spinal muscular atrophy, a congenital neuromuscular condition.

I rely on a motorized wheelchair to get around and need personal support workers to assist me in all aspects of daily living. It’s been this way forever, but now I have colon cancer, and two external abdominal bags to collect various bodily fluids.

This, to put it mildly, complicates things.

My palliative-care doctor is a compassionate young woman who wouldn’t look out of place in a medical drama. She has been guiding me through my own recent hospital drama: I was readmitted to hospital a couple of weeks earlier, for yet another emergency.

I’ve been fighting off a major abdominal abscess for more than a year now. At one point, my abscess was so large, one of my doctors admitted surprise that I was upright. This is what initially led to my cancer diagnosis. A colon biopsy confirmed the cancer was malignant. In October, I was told my cancer was inoperable, despite 28 rounds of radiation.

At least it’s not metastatic. Localized, but nowhere else. For now, anyway. Plus, my surgeon tells me, I likely have years with this cancer. Not months or weeks, like some of his other patients.

The challenge now is the infection associated with the abscess. During this current crisis, antibiotics are working. What my surgeon can’t tell me is when the next infection will hit, or when antibiotics may fail.

Some patients reinfect every month, he tells me. I’ve done well, he adds. I tell him I couldn’t handle being hospitalized every month. He acknowledges I would need to evaluate my quality of life, if this became my reality. In that moment, my decision to seek palliative care early seems the smartest decision I’ve made in a while.

Like most Canadians, I had limited understanding of palliative care before I had cancer. To me, “palliative care” was synonymous with “you are about to die.”

That’s not the case. On my first palliative visit, the doctor explains the word is Latin for “to cloak.” She personally likes that, seeing her role as guide and protector to patients who are coping with the most difficult time of their lives.

I need her guidance. There is no clear path around how to deal with cancer while living with a disability. I’m used to being disabled. It’s my normal. My quality of life up to now has been exceptional, complete with a husband I adore, a sweet, sassy daughter and a brand-new career.

Like everyone else diagnosed with cancer, my life has suddenly imploded. I find myself in this new world, navigating how to continue while knowing the end is coming much sooner than I’d like.

That’s why I’ve sought out palliative care. My own research leads me to studies showing that having a palliative-care expert can help me prolong my quality of life through the management of symptoms, such as pain that I know will likely worsen over time. My family doctor concurs, telling me outright that I need this.

This new relationship has enabled me to talk about my greatest fears. After my conversation with my surgeon, I fear dying slowly of sepsis, waiting for my organs to fail. I’ve agreed to a Do Not Resuscitate order, which ensures I won’t be hooked up to machines in the ICU, prolonging The End.

During this particular admission to hospital and based on what my surgeon has said, my choices seem stark. Down the road, I could die slowly from an infection that will shut down my organs, or sign up for a medically assisted death.

Then, my palliative-care doctor arrives at my bedside. She points out I have bounced back from severe, acute episodes before. She also knows I don’t want an assisted death and takes the time to explain there are options available, such as palliative sedation, a process where I can have large doses of morphine to keep me comfortable. She firmly tells me I am not close to needing this. My goal needs to be focused on getting better and getting home, to my daughter.

As she explains this, I start to relax. She’s given me the window I need to live my life, as compromised as it now is. It is not the life I would have chosen, but it still has meaning. My task now is to figure out what that meaning is. And her task is to help me to define my priorities while maximizing the quality of my life with medical therapies and emotional support.

It’s an interesting time to be thinking of my life as a person who is both disabled and has cancer. Less than two years ago, the federal government enacted a new law enabling Canadians with incurable conditions, whose death is foreseeable and are suffering irremediably, to ask a doctor to end their lives.

It’s been called “dying in dignity,” but for me, that’s not the way I want to go, at the hands of a doctor, wielding a poisoned syringe.

I believe no one with a terminal illness should be forced to endure suffering – but, if there is one lesson for me in the past year, death is not the only way to alleviate suffering. Managing physical suffering feels like traveling a winding road. Some days, it feels never-ending; other days, manageable, almost like the life I had before. Some days are so bad, I’m convinced death really is the only relief, but I’m brought back to reality when I think of what I could miss out on.

My life is definitely smaller now. I doubt I will ever work full-time again. I barely leave my apartment. Thanks to my father’s financial generosity, my husband has been able to take unpaid leave from his work to be with me. The time we spend together is precious. Even in its ordinariness, it is meaningful.

I appreciate the world differently now. It is as though time has slowed for me to see the small details of life, whether it be the softness of my bed sheets or watching snow drift down through my apartment window.

I’m trying to live with dignity, as I always have, despite the very real medical indignities I have been subjected to.

Which is why it dismays me greatly there are continuing attempts to make it easier for people without terminal conditions to ask a doctor to end their life. It dismays me that a lobby organization calling itself Dying With Dignity is not actively lobbying for increased access to palliative and hospice care, or advocating for more community supports for people with disabilities to live as productively as possible. In other words, to live with dignity.

We are all going to die, but before we do, each one of us has a right to a good quality of life, even to the very end. Yet too many Canadians do not have adequate access to palliative and hospice care. The lobbying efforts of those to equalize this are rarely discussed in our media.

I’ve chosen my path, thanks to the help of empathetic doctors and my own advocacy. My hope now is that more Canadians have the right to do the same, without the implied suggestion there is only one real way to die with dignity.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!