BY STEVE MYALL, SACHA LANGTON-GILKS

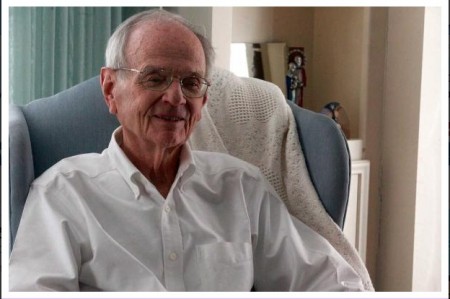

David Langton-Gilks died from a brain tumour in August 2012 at the age of 16 but before his death his mum Sacha planned a peaceful passing for him at home surrounded by his family

Death. It’s the final taboo, isn’t it? Especially when it’s a child. We can’t – or won’t talk – about it.

Sacha Langton-Gilks, the lead champion for The Brain Tumour Charity’s HeadSmart campaign for earlier diagnosis of brain tumours in children and young people shatters that taboo.

To help other parents, she talks about how her son David, who died from a brain tumour in August 2012 at the age of 16, had a peaceful death at home surrounded by his family.

She emphasises that, just like we make birth plans, we should make death plans and how being able to die peacefully at home was her last act of love for her cherished son.

Here Sacha tells her story:

Days before he died, the last lucid words my 16-year-old son David, or DD as we like to call him, said were: ‘I love it here.’ He was looking out his bedroom window into the treetops where, at night, owls – one of his passions – would come to call.

It was just a few days before London 2012 Paralympics and for five years, since being diagnosed with an aggressive, cancerous brain tumour at the age of 11, DD had endured everything globally available on the NHS, including 11 brain operations, years of chemotherapy, weeks of radiotherapy, blood transfusions and a stem cell transplant.

His cancer had now spread down his spine and throughout his brain, leaving him with severe dementia. Unfortunately someone’s child has to be in the 25 percent that don’t survive this type of brain tumour, a medulloblastoma .

Three years on, I can honestly say that giving my child a ‘good’ death – without pain, calm and comfortable in his own bed, in the arms of his family with his beloved cat sitting on the bed, will be my greatest life achievement. And it gives me immense comfort in my grief.

I am speaking out to break a taboo because I remember the silence that hung over parents in the children’s cancer ward when a family ‘went home.’

We all knew that meant the child was going to die but no one could say it.

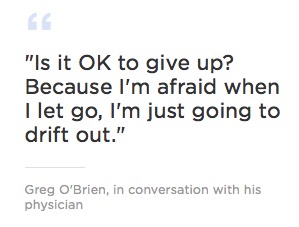

Fear overwhelmed us. If you cannot even say the word, how are you going to be able to discuss what choices best suit your family for end of life care?

With brain tumours being the biggest cancer killer in the UK of children and adults under 40, The Brain Tumour Charity’s feedback from many parents is that they feel completely isolated with no information.

Even doctors do not say the D word because they have been trained to ‘fix’ things and view death as somehow a failure on their part.

But I see my doctors and nurses as geniuses for enabling a fabulous quality of life for my child right up to his death. This taboo about death has to be shattered so that we can improve how we care for our loved ones at the end of their lives.

When I was asked to give a speech to parents and doctors at The Brain Tumour Charity’s first paediatric brain tumour information day about how we managed DD’s death, the process itself, I didn’t know if I could do It. But then I remembered that voiceless fear in parents’ eyes at the hospital.

I call this an ‘ante-mortem class’ – one parent sharing their experience with another parent just as you would at an ante-natal class.

After all, you wouldn’t dream of giving birth without talking to another mum, reading books or going to a class, would you?

Lack of information about end of life care for children breeds fear and stops parents from even being able to articulate questions to their doctors.

On top of this is our society’s obsession with being ‘positive’ with hope. The fear that somehow by saying the D word means we ourselves might have made it happen by not being positive enough, by giving up hope. It is our punishment for being cowards.

But death is part of life and comes to us all. So how can it be negative or positive? It just is what it is – ceasing to be.

When we ‘went home’ after DD’s final scan in May 2012, which showed his cancer was everywhere and he had weeks to live, we were not doing nothing or stopping treatment – there was a detailed advanced care plan in place.

He was having full palliative care treatment co-ordinated by Southampton General Hospital which included Gold Standards Framework for end of life care at our GP’s surgery and also involved Marie Curie.

It centred on the relief of his symptoms of pain and vomiting to give him quality of life.

It just was not curative treatment as this was no longer possible.

But we still had hope – we had changed that hope from one that DD could be cured to one where he had the best quality of life possible in the limited time he had left.

Some people do a bucket list, but DD just wanted to hang out at home with me and his dad Toby, his brother Rufus, now 17, and sister Holly, now 13.

He didn’t want to spend another second in hospital and wanted to have a party with his friends. So we did.

If we had not faced up to the fact that he was going to die soon, we would have spent hours of that incredibly precious time in hospital trying to convince ourselves that the chemotherapy on offer would cure him.

DD would have hated it and we’d have been traumatised by each successive scan, contradicting what we longed to see.

My biggest agony was knowing that helping my child to suffer less meant I might have less time with him.

Nothing will ever be as painful as letting DD go, but how could I have made him suffer pain on my account? That would have made me the most selfish mother alive and I couldn’t have lived with that.

So the biggest battle was actually me.

In Childhood Cancer Awareness Month, from one parent to others going through the same thing, as a gift from my heart, I am sharing how my son died to shatter the taboo and make your battle less.

Complete Article HERE!