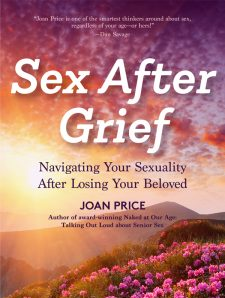

Author Joan Price’s new book focuses on intimacy after grief

In the difficult months after her husband Robert’s death, Joan Price found herself confronted with a veritable mountain of self-help books about grieving. None of them touched on the subject that would preoccupy her for the coming decade: What about sex?

Price is a sex educator, with an emphasis on older people, so perhaps she was primed for this question. But others have noticed this glaring absence in the literature of grieving, too. “The unspoken message, as I received it: keep your mouths shut about sex,” writes Alice Radosh in Modern Loss: Candid Conversations about Grief. “I turned to self-help books for widows, and found that there, too, discussions about sex were pretty much nonexistent.”

Price is used to older people’s sex lives being ignored. “I call it the ‘ick factor’ our society has,” she tells me, when I meet her near her Northern California home. “Eww: old people having sex, wrinkly sex!” she giggles to herself. Price says this ageist notion prevents older people from enjoying their sexuality, a vital part of being human, however old one is.

“We have internalized this ‘ick factor,’” she says. “We see ourselves as undesirable, as over the hill. We see ourselves as needing to say goodbye to sex when things don’t work the way they used to.” And therein lies Joan Price’s mission: to “talk out loud about senior sex,” even in life’s hardest moments. Her new book, Sex After Grief: Navigating Your Sexuality After Losing Your Beloved, seeks to fill the void in grieving literature.

A Life-Changing Love Affair

Seeing Price now, you’d have little external indication that she spent years struggling with the weight of bereavement. The first word I think of when I meet her is “spritely.” Just shy of five feet tall, Price has a twinkle of a laugh that frequently punctuates our conversation, and a playful, vibrant sense of fashion. Her fingernails are painted the purple of grape candy, and she’s wearing dangly earrings of bright, geometric shapes.

At 76, her calendar is filled with giving talks on sexuality, reviewing sex toys for her blog and teaching a bi-weekly line dancing class at a local fitness center.

It was at that line dancing class that a couple of decades ago, Price met the man who would become her husband, an artist named Robert Rice. “He walked in, and I forgot how to breathe,” she tells me. “As soon as he started moving his hips, I lost my place in the dance I was teaching. I just couldn’t take my eyes off this man.”

Price was in her late fifties at the time, already in her second career, having left a job teaching high school for one writing about fitness. The last thing she expected was a life-changing love affair. The blossoming of her romance with Robert nurtured yet another new area of work for her: writing about sex.

“It was an amazing revelation because sex was fantastic with him, but it was not the same as younger-age sex,” she says. “There was much slower arousal… It just took a lot of earnest effort on his part… It was very different. But I was feeling that sex at our age was better, that that wasn’t a defect.”

She wrote a first book, Better Than I Ever Expected: Straight Talk About Sex After Sixty, celebrating that discovery. A second book, Naked at Our Age, sought to answer the questions and resolve problems that older people were experiencing in their sex lives, from what position to use when pained by arthritic joints to a definition of sex that didn’t center orgasm as the only worthwhile goal.

It was when she was just starting to write that book, that Rice was diagnosed with cancer. “I put a hold on everything,” she says. When he died in 2008, Price was completely undone.

“I thought because I knew Robert was dying, that I was getting prepared for it,” she says. “You can’t prepare for that. You cannot know how that bludgeons your brain and your heart. It was all I could do to remember to brush my teeth.”

She would cry all day, pull herself together to drive to the health club, and teach her line-dancing class. Then she’d resume crying in the locker room, and weep all the way home.

A Difficult Subject to Discuss

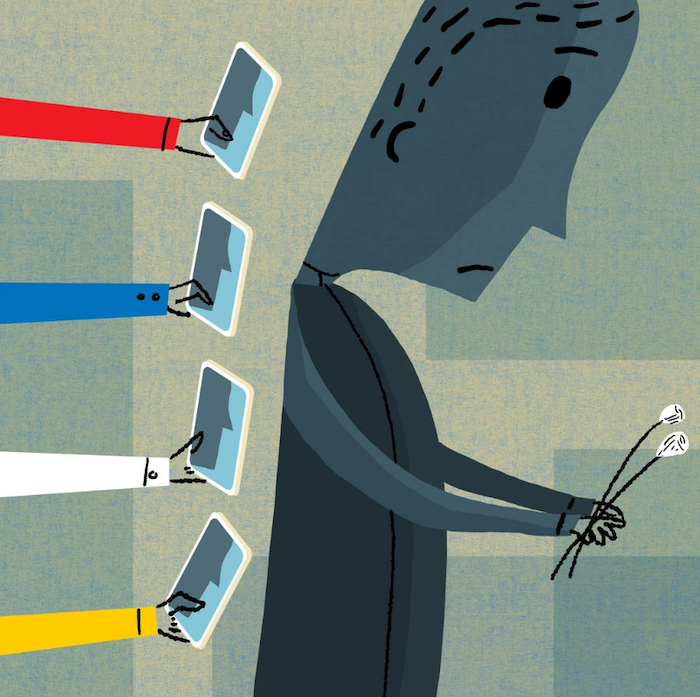

For months, Price writes, her sexuality was dormant. That period of deep grief was followed by the fits and starts of trying to find her way into a new version of her romantic and sex life. This became the fodder for Sex After Grief. Price wanted to give other grievers a manual for navigating the tangle of experiences they might have.

“Some people feel frenetic sexual energy and yearn for a sexual outlet right away,” she writes. “Some start dating immediately, some gradually, some not ever. Some withdraw from sexual possibility. Some share their bodies but not their hearts. Many give themselves sexual release to the fantasy of their lost loved one.” All of these different responses are normal, Price insists. There isn’t one right way to move through it.

“Some people feel frenetic sexual energy and yearn for a sexual outlet right away,” she writes. “Some start dating immediately, some gradually, some not ever. Some withdraw from sexual possibility. Some share their bodies but not their hearts. Many give themselves sexual release to the fantasy of their lost loved one.” All of these different responses are normal, Price insists. There isn’t one right way to move through it.

In keeping with the absence of sex in the literature of grief, there’s been very little scientific research into it, either. One of the few studies of “sexual bereavement,” as its authors term it, came out in 2017 in the journal Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters.

The study revealed that 72% of respondents (who were women age 55 and older) anticipated missing sex with their partner, and that 67% would want to initiate a discussion with a friend about it. But there was also a disconnect: 67% reported that it’d be difficult to discuss sex with a friend whose partner had died, attributing that difficulty to embarrassment.

Price addresses that embarrassment head-on in her new book. She dives into the thicket of myths and taboos of sexuality after loss — from questions of loyalty to one’s deceased partner to how long grieving should last — offering readers scripts for how to respond to advice that doesn’t resonate with their experience.

“Because in the moment, you know, you think, ‘Oh my gosh, am I supposed to take that on?’” she tells me. “’Am I supposed to be embarrassed? Am I supposed to be shamed? Am I doing the wrong thing? Am I doing grief wrong?’ You’re not doing grief wrong.”

Price’s message is clear: our sex lives don’t have to end as we get older, or when our partner dies. Whether we’re having partnered sex or not, she advocates, our sexual selves continue.

The book delves into the practicalities of solo sex, as well as various approaches for dating and different relationship models for older people who may not want to follow a marriage with another long-term relationship, but still want to remain sexually active.

Price is an advocate for thinking about a trusted “friends-with-benefits” arrangement, and quotes a 2013 “Singles in America” study from Match.com that revealed 58% of single men and 50% of single women had had one, including one in three people in their 70s.

‘You’re Not Making Any Kind of Commitment You Can’t Reverse’

She writes about how she kept two journals: one to chronicle the difficulties of grieving and another to record treasured memories that kept her husband alive for her. She writes about feeling out her own personal timetable for when to start having sex again, and with whom.

Price had some false starts, which she found instructive. “If you don’t know if you’re ready to date, it’s okay to try it and then put dating on hold if it feels wrong,” she writes. “You’re not making any kind of commitment you can’t reverse. The same is true for sex. You can explore, then change your mind at any point.”

Price’s own story is one of persistence, of refusing to allow society’s derision of aging bodies to stop her from enjoying her own and of not allowing even the tremendous loss of her loving partner to stop her from engaging with her sexual self. The story, she says, is always continuing.

In the past couple of years, it’s had yet another twist. Price put up a profile on OKCupid, and, after more than a few disappointing dates, she met a retired anthropologist named Mac Marshall who lived nearby. Marshall had recently lost his long-term partner to illness. They shared their grief stories amidst a flurry of other information on their early dates, and in emails.

Price dedicates Sex After Grief both to her husband Robert, “who lives in my memory and in my heart,” and to Mac, “who shows me that joy is possible after grief.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!