“Losing both your parents doesn’t get any easier”

There are painful and sometimes unexpected feelings associated with losing both parents in adulthood.

By Caron Kemp

If it’s possible to have a good death, that’s how I’d describe my mum’s. Within the unlikely surroundings of a quietly attentive intensive care unit, she went peacefully, flanked by her family. It was a mere five months after her cancer diagnosis and none of us believed that the Large B-Cell Lymphoma coursing through her blood, lungs and chest would beat her. But the chemotherapy regime was gruelling, rendering her weak and even more ill at every dose and the final bout of pneumonia proved too much.

I was just 33 and juggling three young children of my own, yet as I sat vigil at her bedside in her final hours, all I wanted was to be scooped up into the arms that once cradled me, to be looked after.

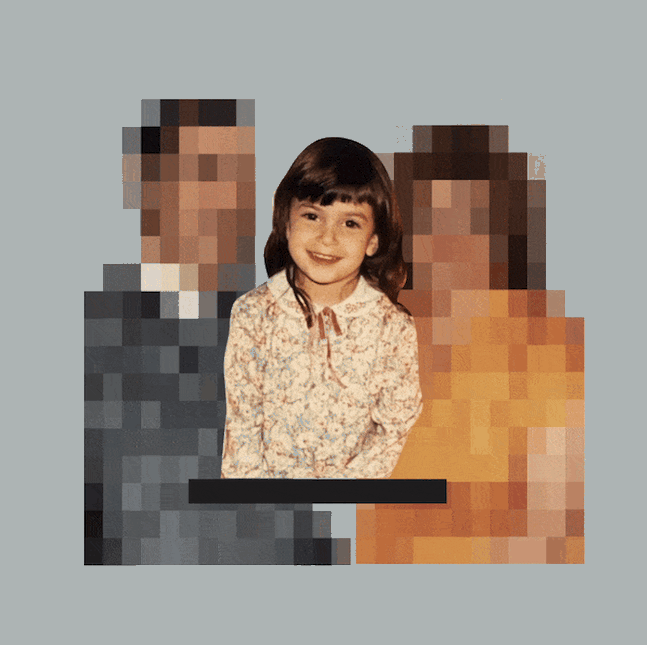

A mummy’s girl to my core, I looked like her, shared many of her quirks and, in her latter years, doted on her as she endured more than her fair share of poor health. Yes, we bickered and, yes, she drove me mad regularly – but my mum was my biggest cheerleader. Even when I failed my driving test over and over again, or felt like I was falling apart at university, she was on hand to remind me of my worth.

Her death hit me hard. However long we’d lived with the realities of hospital visits and hushed conversations, living without her wasn’t an option. The funeral passed in a daze and once everyone else’s world carried on turning, I was left fumbling in the dark for a way to carry on.

Stoic to the end – I’ll never forget the final thumbs-up sign my mum gave as she was put into an induced coma – here was my lead. She never lamented her situation, and neither would I. Her greatest riches in life were her family and I knew all she’d want was for myself and my sister to rally around my dad; her soulmate of more than 35 years, himself bereft and broken-hearted.

“I was left fumbling in the dark for a way to carry on”

So, I poured all my energy into him. I sobbed until I physically hurt, I sought her out in the feathers that landed at my feet, and I got my first tattoo in a big ‘screw you’ to the world. But my dad gave me purpose. Thus, when he was diagnosed with a rare blood cancer exactly two years after my mum died, the cruelty of the situation wasn’t lost on me.

In the seven months that followed, I watched the wisest man I knew become reduced to a shadow of himself; frail, dependant and scared. In the last four weeks – played out from a small, clinical hospital room – life existed in a vacuum, where fear was palpable.

My dad’s death was not a good one. Riddled too with pneumonia and sepsis, I was woken in the middle of the night to news that he’d had a heart attack. He died before we could get to him. It was Mother’s Day.

It was my sister who first helped me try on the title of ‘orphan’ for size. But a fully-fledged adult, juggling a career and motherhood, I felt like the proverbial square peg. Yet here I was, without the greatest anchor in my life, and somehow the shoe began to fit.

Losing both parents is not the same as losing one, twice over. When my dad died, I didn’t just lose him. I lost my identity as someone’s daughter, I lost the family and friends only connected to me through them, and I lost anything standing in the pecking order between me and my own demise.

Plus, without my dad to anaesthetise my pain, I found the wound of my mum’s death finally laid bare too. It was all too much and for weeks I couldn’t muster a tear; numb to the earthquake that had ruptured my world as I knew it.

Life since has been punctuated with plenty of difficult days, but my first birthday without either parent was the toughest yet. However hard it was receiving a card signed solely from my dad, receiving nothing stung so much more. I spent the day at home in my pyjamas, because some things can’t be fixed and at times it’s ok to feel crushed.

Before my dad died, I’d always found camaraderie in others walking a similar path. But this was unchartered territory and it was a very lonely place to be. People tried to empathise. Like the friend of my dad’s – himself in his 70s – who told me he ‘knew exactly how I felt’ having recently lost his second parent. Grief is not a competition, but I can tell you – comparing two completely different experiences hurts.

“There are so many questions that now have no answer and so much I wish I could still weave into our family tapestry”

As someone who struggles with vulnerability, being honest about my feelings is a constant work in progress, yet opening up to the rare few individuals who don’t wipe away my tears, who hear what I say and what I don’t and who share my newfound dark and often inappropriate sense of humour, has been fantastically medicinal.

There are so many questions that now have no answer and so much I wish I could still weave into our family tapestry. But no one leads a perfectly curated life; it’s what we do with our pain that makes the difference.

Losing my parents has been an incalculable, lasting blow, but it’s also been surprisingly freeing. Without anyone to be my guide, I’ve emerged into a new stage of adulthood; finding out who my truest, deepest self is, what serves me well and what really matters. At times it’s been ugly, I’ve been very angry and I’ve lost and found many relationships along the way.

I am also, though, acutely aware of how short and precious life is and I’m more motivated than ever to live mine fully – with my parents’ values and spirit carried with me in my heart.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!