Two years ago, my husband of 18 years took his life. I’m still coming to terms with why.

By Jennifer B. Calder

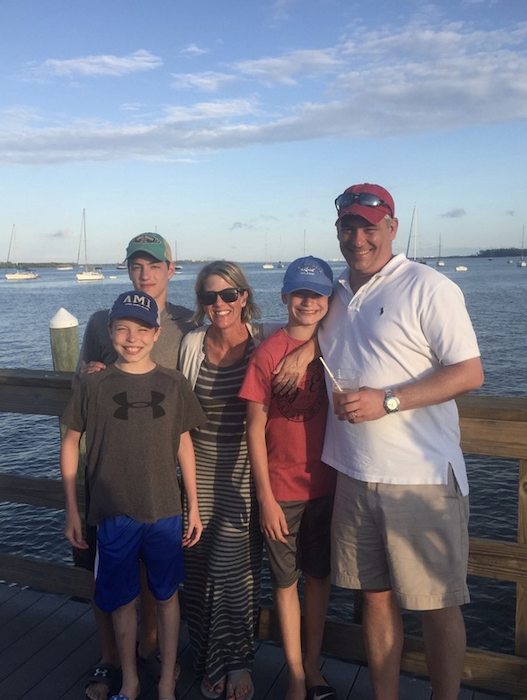

My charming, brilliant, handsomely dimpled, fun-loving husband of 18 years and father of our three sons, ages 12, 13, and 16, killed himself on July 2, 2018.

He was 46.

Was it situational depression after nearly a year of unemployment following previous decades of professional ups and downs? Was it undiagnosed mental illness? Was it noble devotion? Sacrificial, as his letters suggested? Was it desperation?

Or was it, as our oldest son, Logan, said, “A lapse in judgment?”

Or, as our middle son, Grady, asked, “Did Dad love us too much?”

I think it was some combination of all of these.

How much is the life of a father of three boys and a husband worth? Is there a number that makes sacrificing oneself an acceptable, “viable” idea?

Of course not. It’s absurd.

But this is the scenario in which we find ourselves. Trying to make sense of the nonsensical.

On that terrible day, our family became part of a grim national statistic. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of 2018, suicides not linked to a known mental condition comprised 54% of those who take their lives. Suicide rates, overall, are up 30% since 1999, with the highest increase and greatest number among those in middle age — a demographic my husband had just entered.

My husband now occupies a sliver of the pie you see on those impersonal fact sheets, the 16% who take their lives due to financial or job problems. We are now a family reduced to a mom and three sons desperately absent a husband and devoted father, trying to untangle this messy knot.

I watched my blue dot move closer to his on the Find My Friends app as I made my way through Watchung Reservation outside our hometown of Westfield, New Jersey.

His dot — the icon a tiny photo of him laughing, taken years ago on a “date night” — had been stationary for nearly an hour. I’d first activated the app around 3:45 p.m.

My last text from him was at 1:25 p.m., when I asked for reassurance that he’d seen my previously ignored text about taking our youngest son, Beckett, to guitar lessons at 4:30 p.m.

“K” was his response.

Not unusual. His messages were often terse. We joked, the boys and I, that it made him feel hip to use the minimum number of letters.

A little before 4 p.m., I checked and saw his photo near a winding road carving through the woods and assumed he was making his way home after spending the day driving Uber, which he was doing to make additional money while job searching.

I returned to writing the story I had due the next day.

I refreshed the app again at 4:20 p.m. or so. I wanted to see how close he was, to see if I should tell Beck to get his shoes on, but his icon had not moved.

Odd.

I called. I texted. I wondered. No response.

He never showed

So I dropped our son at his lesson and made my way toward him — thinking, assuming, hoping he had taken the extra few minutes between Uber runs to catch a quick nap.

I felt anxious enough, however, not to take the extra moment to IM my boss and tell her I was leaving early

I just wanted to get to him.

He was a big napper

When he worked in New York City, he routinely slept through his train and bus stops on the commute home, texting me to say he was now several stations past our town and making his way back to us.

My most nefarious thought was that he’d picked up some psycho Uber client who had robbed or hurt him.

As I drove, I called my youngest sister in Michigan and one local friend, two of the only people who knew about his attempts to make extra money in this manner (his insistence), and both did their best to quiet my concerns.

“He’s just sleeping” was the mantra I repeated over and over, but as I drove, I scanned oncoming traffic for an ambulance. Something — it was elusive — but something about our last interaction that morning bubbled up and ignited worry in me

I woke earlier than normal and heard Matt come and go from the back door near the garage. I asked about the commotion he was making, and my voice seemed to surprise him. “Oh, you’re up early. I just forgot something,” he said, and he went to leave

I called out in an annoyed, sarcastic tone, “Um, okay. See ya?!” and he stopped and asked me what I’d said.

I heard him take a step toward me in the hall as I was pouring my coffee. I repeated my comment, tossed over my shoulder, because in my pre-caffeine grouchiness, I thought, “God forbid he come and give me a proper goodbye

He hesitated for a moment — a long, silent moment — then turned and left, which I found strange. Normally, a passive-aggressive comment at least got me a kiss on the head.

I forever will be tormented by wondering what might have happened if I had called out an “I love you” instead of a snide comment.

I shrugged and went about my day, thinking of how best to structure my story and hoping the boys would sleep late enough for me to get a good handle on it.

It wasn’t until later that night, after this happened, that I came across our life insurance policy in the “mailbox” we keep at the top of the basement stairs for important bills. And, in the middle of the basement floor, pulled from the dregs of boxes stored in the back closet, I found our bin of important files — birth certificates, marriage license, social security cards, passports, and so on.

The commotion I’d heard earlier came into clear focus.

Matt had been prepping for what he was about to do that day, and when I woke earlier than expected, it interrupted him. A friend graciously theorized that had he come to me and said a proper goodbye, it may have broken the spell of what he had planned

As for me, I forever will be tormented by wondering what might have happened if I had called out an “I love you” instead of a snide comment

Or, conversely, if my bitchy tone made his decision all the easier.

As I drove, I mumbled promises. If I found him unhurt, I would be nicer, kinder

Our marriage had become strained under the stress of yet another job loss, at least the ninth in 18 years of marriage. While polite, we were nearing a breaking point

My queries about a Plan B—a “what do we do next?”—were dismissed.

“It’s under control” was his common refrain, which irritated me, yet none of that mattered as darker thoughts flitted through my mind. I vowed to be a better, more encouraging wife — after, of course, I gave him hell for napping through our son’s guitar lesson while I was on deadline.

I underestimated him.

I underestimated his desperation.

I underestimated our debt to the IRS.

I underestimated his devotion to our boys and his willingness to sacrifice his joy in watching them grow up in order to provide them, in his mind that terrible day, with a potentially stable financial future at the expense of a mentally secure one

I underestimated how much my disappointment with his consistent job losses over the past nearly two decades may have destroyed him.

I underestimated so many things, and for that, I don’t know if I will ever forgive myself.

What if I had been less exasperated? What if I had been more supportive?

What if? What if? What if?

He knew I was nearing the end of my rope. We’d danced this dance numerous times. I’d pull in from grocery shopping or school pickup and see his car in the driveway in the middle of the day. Let go again from whatever job, usually through no fault of his own.

The life of an options trader on Wall Street is precarious, and opportunities grew more scarce as the years rolled past.

We lost our home to foreclosure, along with so many people across the country, after the financial crisis in 2008. A year before that, I went out one morning to drive the kids to school, and my Suburban was missing from our driveway, repossessed for delinquent payments

I went back to work full-time as a writer, but my contributions barely covered the boys’ hockey fees, groceries, the occasional dinner out, and our health insurance.

He refused to talk about the details of our financial life as his unemployment ticked by, month after month.

“I am handling it,” he would say.

And, since he worked in the financial industry, I trusted he did have it under control. This was his area of expertise.

But it angered me. I wanted and expected to be a full partner. It wasn’t that he didn’t know this about me. I didn’t need protection. I have many faults, but being materialist is not one of them. I believe he simply did not want me to worry.

I offered to sell my valuable engagement ring. He wouldn’t hear of it, and that also made me mad.

So, I determined to take the pressure off him and look for a more prestigious, well-paying job. He counterargued that my current arrangement worked well for our family: I was able to work from home unless traveling on assignment, and I had no costs. I never missed a school concert or hockey game, and I made decent money.

His evasiveness and obstruction about our financial position pissed me off. But by that point, nearly everything pissed me off. I didn’t want to create more discord, so I didn’t push it.

“He gave us a great life,” I thought a month or so before this happened, as I looked around our lovely house filled with lovely things, and I wanted, I thought, to tell him this. But I was stubborn, annoyed, and fed up and couldn’t bring myself to thank him.

I also thought, this go-around, tough love might be better.

I was frustrated.

I was frustrated by the consistency of his car showing up back in our driveway during the workday.

I was frustrated by the thought of college in two years for our oldest son while we struggled, renting a house.

But I was mostly frustrated by his refusal to talk about other options, his stonewalling, his insistence that he had things under control.

And now, I guess, it seems he had a plan all along.

When we had our kids, we decided my job would be to stay at home with them. Which I absolutely loved. Not that life wasn’t challenging with a newborn, one-year-old, four-year-old, and neither help nor relatives nearby. It was much more difficult than my previous job running a gallery in New York City. Although I have a master’s degree in art history, my salary would have barely covered daycare for our three boys, and this privately thrilled me.

I was disillusioned with my career by that point. I loved my artists, but I’m more academic in temperament and not a natural salesperson, which made me ill-suited to the commercial art world.

But in hindsight, it seems silly.

Worse than silly — tragic. Placing our family’s entire financial burden on him was ridiculously unfair

After drinking too much wine one night, I told him how proud I was that he was driving Uber while job hunting.

He told me he didn’t want to talk about it.

Maybe he thought I was being sarcastic, but I wasn’t, and I hope — I truly hope — he knew I was sincere

I found him honorable

I encouraged him to tell our boys the truth, but he refused. He felt ashamed and told the boys he was “consulting.”

Worst-case scenario, I thought our marriage might not survive, although all the solutions and future plans I suggested — moving somewhere cheaper, a new career of teaching and hockey coaching for him — involved the five of us.

I wanted us to go to marriage counseling once he found a new job. I didn’t want to pile onto what was already an emotional and stressful time by doing it earlier.

We were a great family, the five of us. Even when our marriage was challenging, as a family unit, we were fantastic.

Enviable

We truly loved being together. Maybe it was because we had no family close by, but any discord we may have felt with one another as spouses evaporated when the five of us were together. Which was constantly.

We had a blast. The jagged edges of my bossy, Type A personality were rounded out by the easygoing nature of his.

Well, at least in the beginning of our relationship.

Over the years, his inability to walk away from an argument, his inflexibility — although he was often right — was tempered by my more level-headed outlook, and I advised him to better pick his battles (not that he listened much). Still, he could make me laugh at myself and vice versa.

And we laughed a lot.

We joked and teased and made incredible memories together, creating a family shorthand only we understood: random words referencing an entire vacation the summer before, “Choo Choo byeeeeeeee,” and so on. We were an affectionate family, hugging and kissing and sharing “I love you’s.”

Although life at the moment muddied the waters, I believed the detritus would eventually settle. I thought we would return to clearer waters.

Divorce was my worst-case scenario. Our endgame. Not this.

He broke the deal.

On the map, my blue dot eventually, finally, gratefully overlapped with his as I spied my car and pulled into the tiny parking lot on the edge of the woods.

I was in his small BMW, which we’d bought in 2000, before we had our first son, and I parked next to my truck. He earned more money driving Uber in a larger car, hence, he’d taken over my 2006 Suburban.

I immediately knew something was wrong.

He was not in the car.

Either someone had hurt him or he’d gone into the woods to use the bathroom and had a heart attack. The app told me the car had been parked in the same spot for more than an hour, and it was so very hot that day.

Either way, I knew I needed help.

I got out of his BMW and began to dial 911, my heart ticking up in beats, thumping in my ears.

Then I heard the engine of my truck running.

I tried the driver-side door, and it was unlocked. I disconnected with 911 before anyone took my call. Opening it, frigid AC blasted me, a stark contrast to the 105-degree real-feel temperature outside.

I glanced into the back seat and had a moment of pure, gloriously unadulterated relief.

His legs.

They are seared into my mind, no matter how many times I shake my head to clear the image. His legs, crossed at the ankles, socks and sneakers and, farther up, his khaki shorts and a gray souvenir T-shirt from Anna Maria Island, where we had spent our last spring break.

In half the time it takes to exhale, I felt such extreme happiness and a smidge of annoyance.

Yep, napping.

He missed taking our youngest son to guitar lessons because he was sleeping while I had a story due, and now he’d made me drive into the middle of the woods to find and wake him.

But almost simultaneously, I saw an enormous brushed-aluminum cylinder tipped on its side. It took up most of the space between the two captain’s chairs in the second row. I would later learn it was a helium tank from a nearby party store — used to make balloons for children’s parties, not death.

I climbed through the front seats and onto his body, following the tube taped to the tank.

I didn’t see his bag-covered head at first; it had tipped back behind the seat as if asleep. A mask over his mouth connected to a tube under the bag, a bag you would use for a roasting turkey, and its string was pulled tight around his neck. I easily ripped it off and slapped his face, his head hanging back and his brown eyes half-opened while I screamed, “No! No! No!”

I could still hear the hissing of gas.

The force of my hand repeatedly striking his face moved his head back and forth and, for a grateful moment, I mistook this as responsiveness.

But then I saw his left arm resting on the canister. The top was yellow and, along the bottom, gravity had pulled the blood down, turning the entire length of it a mottled red.

I redialed 911, screaming, got out of the car behind the driver’s-side door and moved around the back of my truck to the rear passenger door nearest him. I did not feel a pulse but knew I needed to try CPR.

He was so heavy, and although the seat he was in was reclined, it was not flat. I knew that in order to administer CPR, he had to be flat. I tried, but I could not budge him out of the car on my own. Although we were in the woods, we were near a street. I stood in the middle of the road, my hands up, still connected to 911 and implored, screamed for people to stop and help me.

No one did.

As the mom of three boys, I have become, over years of many, many injuries, unnaturally calm in moments of crisis.

But not now.

Precious minutes ticked by as car after car swerved around me, no doubt frightened off by my panic.

The 911 operator kept admonishing me to calm down, repeatedly asked for my location and scolded me for my hysteria. But I had no idea where we were, having taken an odd, circuitous route through the reservation.

My inability to tell them our location only increased my desperation and the sheer horror I felt.

I continued to fail him.

Finally, an older woman with short gray hair and wearing a floral scrub top stopped, took the phone out of my hand, and directed them to our position.

Then another car stopped. And another. I remember one woman had a small child in the back seat, visible through the open window, and I shouted at her to stay in her car. I didn’t want her child to witness this.

The ambulance seemed to arrive quickly. They immediately pulled Matt’s body out of our car and onto the the uneven gravel of the parking lot. No one would let me near him. I can still feel their hands on me, holding me back.

I texted my sister, who had been calling repeatedly and getting my voicemail, two words: “He’s dead.”

She thought I meant it figuratively, that I’d found him sleeping and was irritated to have left my workday while on deadline only to find him napping. She called again, and apparently I answered. She recalls hearing nothing but my screams.

With uncontrollably trembling hands, I called my friend and asked her to gather my boys from their various positions around town. Her hysterics matched mine, and she later said I told her to knock it off, to pull herself together, hide her emotions, and get my kids home, words of which I have no memory.

She did. How, I have no idea, but she did.

I watched them working on Matt on the rock-strewn ground of the parking lot, weeds sprouting behind him, cutting his T-shirt to expose his chest. His body violently lurched over and over from their efforts, but I knew he was gone.

I knew he was gone from the moment I saw his arm in my car.

I had a fleeting hope that they could revive him, at least long enough for the boys to say a proper goodbye in a hospital. I asked where they were taking him and if could ride in the ambulance.

I then had the fear that he would be brought back enough to survive but not enough to actually live, and I didn’t know what to wish for in that moment.

I sat on the bumper of his car, my legs bouncing in hysteric motions mimicking my insides, drinking water a kind bystander had pushed into my hand.

I tried to focus on the bystander, on her commands to take deep, slow breaths, but I couldn’t make my body obey.

I saw Matt through the side door of the ambulance, his body now on a gurney. By this point they were working on him in the rig. His handsome head, with his salt-and-pepper hair, was perfectly framed by that door, like in a movie.

Then, suddenly, they stopped.

Snapping off their plastic gloves, they all stepped away, and he was alone.

It was then, for certain, I knew he was gone.

A howl that did not sound human escaped my body. I remember the noise startled me and it took a moment to realize I was the one making it.

It was 5:19 p.m.

Time of death: a little over a half-hour from when I’d called 911 at 4:46 p.m.

In the car were three letters: one to me, one to our boys, and one to his parents. I hadn’t noticed them during the chaos and my panic. They accompanied his birth certificate, passport, wallet, cellphone, and copies of various bills. From this evidence, I can only assume he never expected I would be the one to find him.

We talked often about odd people he picked up and stories on the news of Uber drivers who had been hurt. I believe he thought I would call the police to check on him before going out to the woods alone, which in hindsight is probably what I should have done.

I’m forever grateful I didn’t go out there with one of our kids.

But it hurts to think he assumed I would not search for him, that he would need various forms of ID for police to tell us he was gone. If it were reversed, he would have hunted for me, and it destroys me that he did not consider I would do the same.

After, I could not speak.

I rotted my throat with my screams for help. Crackly, gaspy sounds were all I could make for days. A bruise covering my entire upper thigh appeared the next day, visible proof of my efforts to drag his body out of our car. I caught myself staring at that bruise over the following days, trying, unsuccessfully, to convince myself there was nothing more I could have done to save him.

I have no idea how much of this is my fault.

The letters, which I was not allowed to read on-site for reasons that still baffle me, were paraphrased by the kind, on-scene chief after I begged and pleaded for some insight.

Not that it helped.

I mean, when I finally read them, word for word, days later, it did.

I understood how he got from A to Z in his mind.

Sort of.

I understood the sliver of the prism through which my husband viewed our lives and future, but I remain perplexed by his inability to recognize how distorted his theory became as it passed through this spectrum.

While he potentially fixed our financial problem, he created a million more that splintered off in bouncing, inaccurate, agonizing directions that were infinitely harder, if not impossible, to solve.

And this makes me so angry. We created three amazing boys who are all on really incredible paths, and I don’t know how I will forgive him if this knocks them off track.

Or myself.

They are this way because they had a dad who loved them so very much, who spent time with them, had conversations with them, valued their opinions. He coached all three of their hockey teams, spent years making memories together with them on the drive to and from chilly rinks.

While unemployed, he dropped them off and picked them up from school, went to the grocery store, and cooked dinners. He played video games with them, tossed a football, made huge breakfasts every weekend.

He adored them. Plain and simple.

He loved them more than anything.

Kids aren’t supposed to be your best friends, and Matt was good at not blurring those lines. He was a disciplinarian, but they secretly were his best friends.

In his letter to them, he oddly signed it “Matt and Dad.” A friend theorized it was because he truly thought of them as his friends, not just his children.

How can your dad taking his own life so that you may have a “better” future not screw you up? The night before he killed himself, we had a family movie night.

The pick, A Quiet Place, was a random selection.

Prior, Matt went to the store to buy microwave popcorn for the boys and made each of them specialized milkshakes. In the movie, at the end (spoiler alert), the dad sacrifices himself to keep his kids safe.

Our boys were upset by this, but we explained that’s the job of a parent. That either of us would do anything to keep them safe in a similar situation.

I have no idea if that triggered a plan he’d long had in the making, but the timing doesn’t make sense to me otherwise.

As dumb as it sounds, he had just received a new batch of plastic cups for his iced coffee. We’d talked about either a beach day or an amusement park for the Fourth of July and had two family vacations planned. This may have been his fallback plan, but I believe its implementation was set into action after the movie that night.

I later learned from the police that Matt rented the helium tank at 8:30 a.m. He was still alive at 1:25 p.m. when he texted me.

This tortures me.

I cannot envision the pain he was in, the courage he was trying to muster, the possible debate he was having with himself, knowing what a horrific idea this was, the damage it would inflict on all of us — but believing without his life insurance policy, our lives were doomed. He thought he ran out of road, which is nonsense.

There is always more road.

He made the choice to kill himself not because he wanted to — if we were financially stable, he would still be here. He didn’t suffer from chronic depression. He sacrificed himself so his family might, in his twisted view on that terrible day, have a chance of a more secure future financially — but a severely diminished one in all the ways that truly matter.

He believed we’d be better off without him.

He also robbed his parents of their only child.

How wrong he was.

In his letter to the boys, he wrote, “You will get past this, you will go to college, fall in love and marry and have families of your own. I hope you can forgive me and understand.”

With every fiber in me, I hope he is right, although I know that is an impossible request.

A loving, present dad is unquantifiable.

Irreplaceable.

The worst moment of my life, finding my husband dead in our car, would be eclipsed by something even more horrific: having to tell our three adored sons he was gone.

The officer, who held my hand the entire ride home, dropped me off down the block, at my request, so the boys wouldn’t see the police car.

Every step I took up our driveway made my legs quake, knowing, as I got closer to our front door, that I was about to cross a line separating “before” and “after,” and nothing would ever be the same.

I have no idea how much of this is my fault.

It could be most of it. It could be if I had been kinder, more supportive, more encouraging, we would not find ourselves here.

It could be the opposite, that nothing I could have said would have swayed him off this course.

It’s all too fresh. I don’t have any answers. And maybe I never will.

All I know for certain is that I am now the solo parent to three extraordinary boys.

Boys who were shaped by a loving and exceptional father.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Grief expert David Kessler on the power of finding meaning during the COVID holidays

By Karen Ocamb

How can emptiness be so oppressive? Absence hangs darkly in the air, a steadily descending, suffocating pall of grief threatening to choke out the joyous light of life. Obligatory smiles are forced around the family dinner table. Tears are not, falling unexpectedly with flash images of happier times. Death did not take a holiday this year.

This Christmas, the families, friends, and loved ones of the more than 9,000 people who’ve died from COVID-19 in Los Angeles County will struggle with the grief. Loss upon loss upon loss—not only death but job loss, the loss of financial and relationship security, the loss of feeling in control of one’s own life—suffered in silence creates a numbness that can make even the simplest task a struggle.

David Kessler understands and wants to help. During the height of the AIDS crisis, Kessler, the gay founder of Progressive Nursing Services, helped care-providing friends of those dying from the stigmatized disease cope with their fears and grief, later cofounding Project Angel Food with his friend, former presidential candidate Marianne Williamson. Kessler subsequently teamed up and wrote two books with his mentor, psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who pioneered the concept of the five stages of grief in her ground-breaking book On Death and Dying. After the 2016 accidental overdose death of his 21-year-old son during the opioid crisis, Kessler wrote Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief, about “remembering with more love than pain.” On his website Grief.com, Kessler posts helpful videos, including one in which he shares how to heal the five areas of grief, as well as resources and help with myriad feelings not generally associated with grief. He also started a free Facebook group so people can connect virtually.

“It’s really important that we name our feelings because you can’t heal what you don’t feel,” Kessler tells Los Angeles. “People don’t realize that grief is exhausting and that heaviness you’re feeling, that sadness, that lack of motivation—there’s a good chance this time it’s grief. And when we name it, we no longer feel we’re crazy or something could be wrong with us. Grief is a reflection of what’s going on in our life and in the world. And how many losses are there right now?”

Every day in L.A. is a 9/11. “The problem is we can’t see this,” Kessler says. “Because it’s everywhere and there’s no funerals and there’s no visuals. Our mind can’t comprehend what’s really happening. When you look back on the AIDS crisis, the Vietnam war, 9/11—there were caskets and nonstop funerals. We are not seeing that. Now we’re at home. Funerals are rarely happening, and if they are, they’re on Zoom.”

Meanwhile, the comfort of physical contact with loved ones who live outside our households has been temporarily taken away. And we’re subconsciously mourning little things every day. Even discovering that a beloved neighborhood restaurant has shuttered can trigger grief.

So what do we do?

“Part of our work is to try to find a meaning. Now, meaning isn’t in the pandemic. There is no meaning in a horrible death or a pandemic. The meaning is in us,” Kessler tells Los Angeles. “I live on a street here in Los Angeles where I never knew my neighbors. I mean, I kind of waved at the people to my right and to my left, but I didn’t know them. During the pandemic, all of a sudden, we got a whole text chain where we started texting one another. Someone was going to the grocery store. Check on the elderly man at the end of the street because he may need groceries. That was finding meaning. All of a sudden, I saw kids in the front lawn playing with their parents. I’ve never seen them play with their parents. That’s meaning. We’re suddenly, ‘well, it’s so horrible, we can only connect on news.’ But suddenly, we’re talking to people around the country, around the world on Zoom.”

Kessler hopes that people find a lot of new meanings. “Maybe part of the meaning is that we take our government personally. Maybe we make sure that we’re fully in line with our government and the future and that our government really represents us,” he says.

And what of finding meaning during a holiday season in which cheer seems like an insult?

“Love is still important,” Kessler says. “Even if I just have conversations with people I love. Even if I realized that this is going to pass. Sometimes some of those worst moments become the meaningful ones when we’re no longer having superficial conversations with each other. I can’t tell you how many people have said, ‘I just can’t go commercial on a lot of gifts or do that whole thing this year.’ It’s going to be more love than commercial gifts. Maybe we’ll be a little more meaningful this year.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!