— Why food plays a major role in Irish wakes and funerals

Irish funerals and wakes since ancient times have always highlighted the importance of food, feasting and hospitality

As one of those who lost an elderly parent during the pandemic, we were unable to give the appropriate ‘send-off’ to a member of the older generation who would have fully expected one. I found myself at one stage mechanically making two sliced pans worth of sandwiches in my late mother’s kitchen, forgetting there would be no mourners coming to serve them to due to lockdown restrictions.

This brought into sharp focus the real function of funeral hospitality: without visitors to share the food with, my immediate family lacked the impetus – or the appetite – and the food was thrown out days later. It’s the rituals that help make a funeral. Often we don’t know why, but we enact them in the knowledge that it’s what we’re supposed to do. Without the anchor of a set of traditions to follow, the days around a funeral, difficult enough to navigate with grief, felt even more rudderless at the height of Covid.

Providing appropriate provisions for guests was a deep seated concept in Ireland. Under the Brehon laws, a householder was required to offer food and lodging to any traveller passing through. The higher a guest’s social status, the higher level of hospitality they expected to receive.

Later, great funeral feasts were held for Gaelic chieftains where the new heir marked his succession by providing ceremonial meals for mourners. These funeral banquets were as much about the heir’s generosity for appearances’ sake. Lavish hospitality could help advance a family in Gaelic society by demonstrating prestige and power.

Stakes were high, and guests with elevated expectations could be quite judgemental about what was on offer. Guests attending funerals expected good food and drink to be served. Traditionally, mourners were provided with food and drink to provide sustenance while they sat up with the corpse through all-night wakes. Partaking of hospitality was one of many rituals that, once enacted during this liminal period, was another stage in signifying the soul of the deceased passing over into the next realm.

Perhaps therein lies the roots of Irish generosity in such circumstances: legislated in old Irish law and as a concept in tradition, it became innate in folk custom that it was right and proper to offer appropriate hospitality. It was also considered ‘unlucky to refuse’, and the superstitious time around a funeral was not one where people took their chances with luck.

By the early 20th century, bestowing hospitality despite humble circumstances was a key tenet of Irish identity. James Joyce wrote, albeit ironically, that “the tradition of genuine warm-hearted courteous Irish hospitality, which our forefathers have handed down to us and which we in turn must hand down to our descendants, is still alive among us.” The idea that generous hospitality must be extended continues to be key in most Irish celebrations and feasting today. Being conscious of appearances and not wanting to let the side down or being seen as ‘stingy’ can lead to the often-extravagant spread at Irish gatherings.

The multi-use table

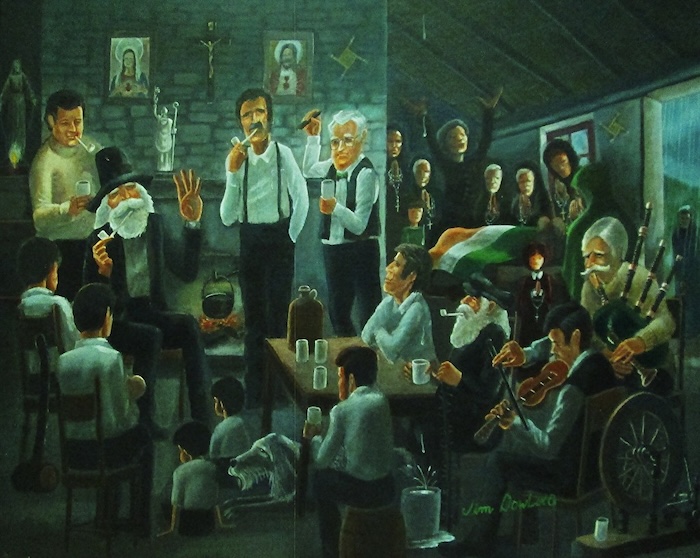

From the post Famine period and into living memory, the ‘feasts’ that maintained formal dining seated at tables were wedding breakfasts and harvest feasts. Funeral catering involved simple food usually served ‘in the hand’ or passed around to mourners informally seated while conversing. These would have been much humbler than the medieval banquets of old.

At Irish wakes throughout the 19th century, sitting at the kitchen table for hospitality was off-limits, because that piece of furniture was a focal point for reasons other than food. The kitchen table or ‘bord’ might alternatively contain an altar or the corpse itself. When laid out and ready to view on the table the corpse was termed ‘over board’. According to the funeral director David McGowan, this term persisted into living memory.

In earlier times at wakes, the long wooden stretchers underneath the tabletop might be where the corpse was laid out, while the tabletop was used as an altar. Most families would have lacked appropriate furniture to serve the large number of mourners in a formal manner, and neighbours often loaned furniture and crockery.

‘Wake provisions’

As one of the key events in Irish life, guests not only fully expected ‘a good spread’ at a funeral but it had also been also keenly anticipated by the deceased that they would have, and be given, a ‘good send off’. In the more recent past, even the poorest people saved money so that their funeral could be catered suitably.

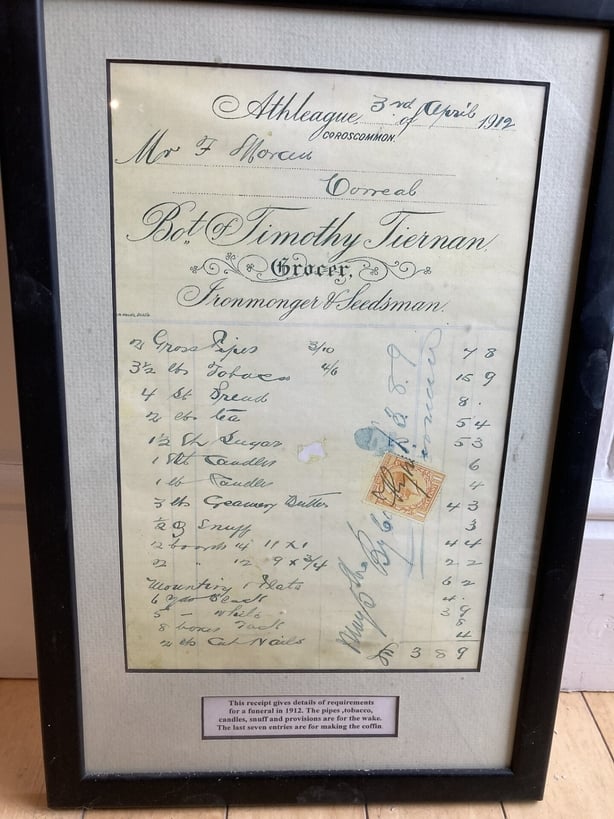

At a time of frugal diets, dominated by potatoes and buttermilk, a funeral offered a chance to feast on treats: tea with sugar, bread with jam, a glass of whiskey, good tobacco. These were key on the shopping list known as the ‘wake provisions’.

The custom was that male relatives of the deceased were responsible for going to the local grocer to collect this. The men had to do this in pairs, to have another to-hand for protection from any evil spirits at a potentially dangerous spiritual time. The wake provisions included clay pipes and tobacco, alcohol such as porter and whiskey, along with tea, shop-bought white bread, jam, sugar and meat.

In the past, wakes and funerals, along with fairs and pilgrimages, were large gatherings that allowed a usually dispersed rural community to come together. Many wakes were places for young people to stay up late and socialise, and some wake games facilitated flirtation and courtship. In addition, the serving of treats and alcohol gave a party atmosphere that along with some of the ‘heathen’ customs involved drew the ire of the Catholic Church.

Funeral hospitality today

Although many customs have died out, the funeral in Ireland retains an importance as a collective event, and one where hospitality remains important. Today, this is more formal, invite-only and restrained when compared to the past, when mourners would simply turn up at the house when they heard keening begin. Wakes are now often denoted as ‘house private’ or take place, carefully regulated, in funeral homes.

Any home catering is usually informally served tea and triangle-cut sandwiches, (egg mayonnaise, or ham, or cheese for vegetarians) along with cakes and scones. Church services are followed by cremation or burial, and the ‘afters’ now usually take place at a hotel, where that intrinsic Irish hospitality is remnant in the form of a sit-down meal for invited guests.

Post Celtic Tiger, Irish hotels have become the real engines behind the hospitality for life events that once took place in the home: funerals, weddings, and other celebrations. Hotels and their staff can offer a fascinating lens through which to observe contemporary Irish customs and rituals.

One Irish chef I spoke to observed that ‘hotel’ funerals are not as big as other such events, guests do not linger long and there is a reluctance to take alcohol as many are driving. “From what I’ve witnessed, formal sit-down [funeral] meals are a much quieter affair where people don’t really know how to ‘be’“.

The formalities therefore tend to stifle the atmosphere. The wish to offer substantial hospitality to guests, versus what the guests might actually prefer, and the struggle to figure out what is appropriate these days – food truck? Barbeque? – is a particularly modern Irish conundrum, and one that might be solved by a return to slightly more traditional rituals.

Sean Moncrieff recently wrote of the comfort of funeral food from a mourner’s point of view, and how it is an evocative part of the grieving process. From the point of view of the bereaved, serving and interacting with guests (be it at a wake house or hotel) offers a welcome fleeting distraction from grief. It gently encourages eating and engagement at a time when the stomach feels hollow. To this day, wherever the location, offering and partaking of hospitality, and ritually sharing and consuming, all continues to be an essential part of the Irish funeral tradition, and will continue to be in whatever form it takes in the future.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!