By ashley cowie

Any parent must agree that one of the greatest hardships experienced around the death of a family member is having to explain to children what happened and what happens next? Should you tell them the stark truth; that the fun and games don’t last forever? What sort of words will you use; dead, died, passed away, lost, crossed over, or went to sleep? This is a problem with very, very ancient origins. Ancient death rituals offer up evidence for this.

Since the beginnings of civilization, whenever and wherever, parents have had to teach their children how to grieve, commemorate, and dispose of deceased loved ones. And in the ancient world death was an infinitely more complicated affair, evident in the bizarre death rites practiced from culture to culture around the world. Here are some of the oldest funeral rituals in history, ones that take death to a whole new level of macabre.

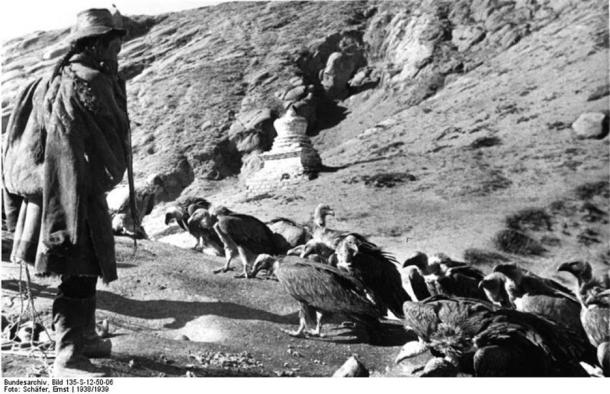

Zoroastrian Sky Burials

Zoroastrianism; the ancient pre-Islamic religion of modern-day Iran, was founded about 3500 years ago and still survives today in India, where the descendants of Iranian (Persian) immigrants are known as Parsees. A 2017 article by scholar Catherine Beyer, Zoroastrian Funerals, Zoroastrian Views of Death, describes the first step in Zoroastrian funeral rites, where a specially trained member of the community cleansed the deceased “in unconsecrated bull’s urine.” The corpse was then wrapped in linen and visited twice by ‘Sagdid’ – a spiritually charged dog believed to banish evil spirits – before it was placed on top of the ‘Dhakma’ (Tower of Silence) to be torn apart and finally devoured by vultures.

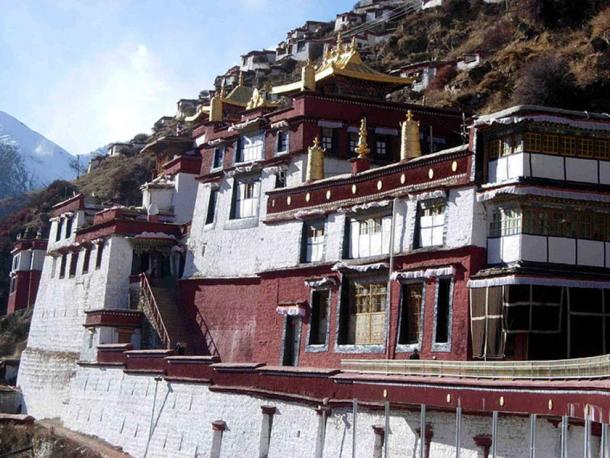

Tibetan Buddhist Celestial Burials

Similarly to ancient Zoroastrians, today, about 80% of Tibetan Buddhists still choose traditional “sky burials.” This Buddhist ritual has been observed for thousands of years and it differs from the Iranian/Indian rituals because the deceased were/are chopped up into small pieces and fed to birds, rather than being ‘left’ for the birds.

While at first this might seem nothing short of brutal, verging on undignified, a research article published on Buddhist Channel explains that Buddhists have no desire to commemorate dead bodies through preservation, as they are thought of as shells – empty vessels without a soul. What is more, in their doctrines, which promote ‘respect for all life forms’, if one’s final act is to sustain the life of another living creature the ritual is actually a final act of selfless compassion and charity, which are primary concepts in Buddhism.

Native North American Totem Poles

Native cultures in the American Northwest carved wooden Totem poles to symbolize the characters and events in myths and to convey the experiences of living people and recently deceased ancestors. The Haida people from the Southeast Alaskan territories tossed their dead into a mass grave pit to be scavenged by wild animals.

However, Marianne Boelscher tells us in her 1988 book The Curtain Within: Haida Social and Mythical Discourse that the death of a chief, shaman, or warrior, brought with it a complex and bloodthirsty series of rituals. Dead shamans, who were thought to have cured the sick, ensured supplies of fish and game, and influenced the weather, trading expeditions, and warfare, were chopped up and pulped with clubs so that they could be stuffed into suitcase-sized wooden boxes. Once pressed inside, the boxes were set atop mortuary totem poles outside the deceased shamans’ homes to assist their spirits’ journey to the afterlife.

Endocannibalism

Known to anthropologists as “endocannibalism” many ancient cultures disposed of their dead by eating them . Herodotus (3.38) first mentioned ‘funerary cannibalism’ as being practiced among the Indian Callatiae people. Furthermore, the Aghoris of northern India were said to “consume the flesh of the dead floating in the Ganges in pursuit of immortality and supernatural power,” according to an article published on Today.

The ancient Melanesians of Papua New Guinea and the Wari people of Brazil both held “feasts of the dead,” where they attempted to “bond the living with the dead” and to express community fears associated with death. Some specialists believe that endocannibalism is something the dead might have expected as a final gesture of goodwill to the tribe and their direct family.

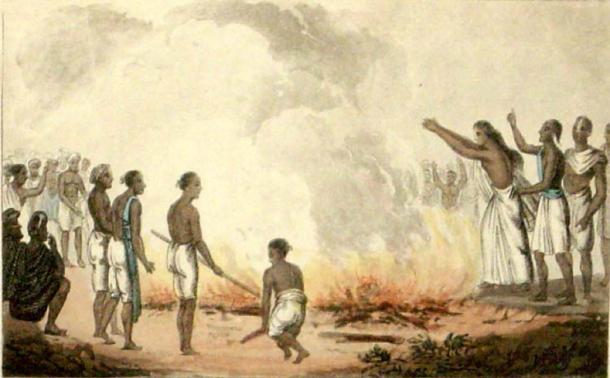

Sati – Burning The Widow

Sati (suttee) is an ancient funeral custom practiced by the Egyptians, Vedic Indians, Goths, Greeks, and Scythians. Banned mostly everywhere today, Sati required widows to be burnt to ashes on their dead husband’s pyres; sometimes voluntary ending their lives, but there are many recorded incidences of women being forced to commit Sati, which is murderous, inconceivable, and beyond any reason.

Robert L. Hardgrave, Jr. is Temple Professor Emeritus in the Humanities, Government and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin. In his informative book The Representation of Sati: Four Eighteenth Century, the Sati ritual is considered as having maybe originated to “dissuade wives from killing their wealthy husbands” and it was sold to the public as a way for husband and wife to venture to the afterlife together.

Sacrificial Viking Slaves

While the threat of a Sati ritual must have utterly terrified Hindi women of all ages and creeds, the death of an ancient Scandinavian nobleman, according to Ahmad ibn Fadlan, a 10th century Arab Muslim writer, brought funerary events of an “exceptionally barbaric nature.” After the death of a chieftain, his body was placed in a temporary grave for ten days while a slave girl was ‘selected to volunteer’ to join him on his passage to the afterlife. The sacrificial maiden was forced to drink highly intoxicating, psychedelic mushroom enhanced drinks, and as a way “to transform the chieftain’s life force” she was forced to have sex with every man in the village who would all say to her, “Tell your master that I did this because of my love for him.”

A 2015 Ancient Origins article written by contributor Mark Miller titled The 10th century chronicle of the violent, orgiastic funeral of a Viking chieftain explored these rites in detail and explained that after what amounts to constitutionalized ‘rape’, the girl was taken to another tent where she had sex with six Viking men. The last man strangled the girl with a rope while the settlement’s matriarch ritually stabbed her to death. The chieftain and his slave girl were finally placed on a wooden ship to take them to the afterlife.

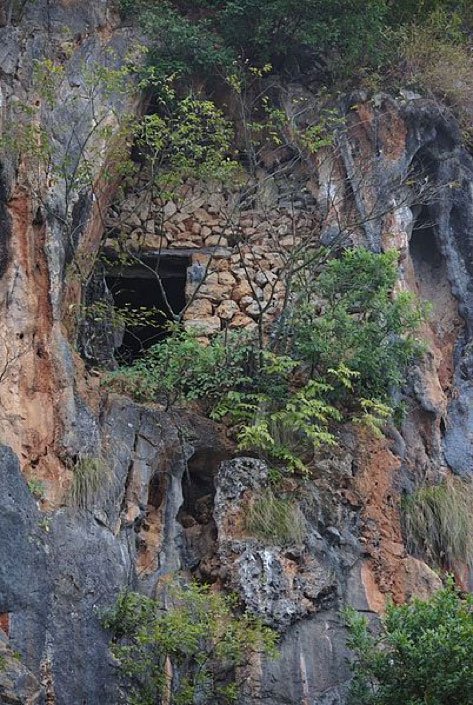

Somewhere Between The Above And The Below

In 1573 AD, the Bo people of southern China’s Gongxian County were massacred by the Ming Dynasty and are today all but completely forgotten, if not for their mysterious 160 hanging coffin baskets located almost 300 feet (91 meters) high on cliffs and in natural caves above the Crab Stream. A China.org article informs that locals refer to the ancient Bo people as the “Sons of the Cliffs” and “Subjugators of the Sky”, and murals surround the coffins that were executed with bright cinnabar red colors illustrating the lifestyles of the ancient slaughtered people.

What Can We Learn from Ancient Death Rituals?

Having skirted over some of the ancient world’s death rituals, we are now hopefully better equipped to answer those questions that our children will inevitably ask us. You might be well served to offer your child the words of author Robert Fulghum: “I believe that imagination is stronger than knowledge. That myth is more potent than history. That dreams are more powerful than facts. That hope always triumphs over experience. That laughter is the only cure for grief. And I believe that love is stronger than death.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!