Death doula Jane Whitlock on end-of-life care, grief, and the importance of telling our death stories

When her husband got sick with kidney cancer and died four months later, Jane Whitlock, having had no experience with death or grief, found that the guidance and spiritual care provided by hospice just wasn’t enough. Resolving to find her own purpose while answering for the gaps she saw in end-of-life care, she followed her intuition and became a death doula.

A death doula, or end-of-life doula, is someone trained to provide holistic care to a dying individual. There is no nationally standardized certification program, which means there are multiple training options—a process that involves a set of training classes and documented hours of direct client support, plus whatever specific assessments a particular certification program requires. Death doulas represent a growing movement toward redefining our typical approaches to death.

A death doula’s role is as nuanced as each individual who occupies that role, and Jane Whitlock sees herself first as a companion. She provides comfort and support to the dying individual and their “tribe”—as she often refers to the circle of family and friends—through a time for which most people may not be spiritually prepared. Through intentional connection, she deciphers how she and the tribe can best serve the dying person. She abides by the slogan, “Death: it’s a collaborative event!”

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

The Growler: Why do you believe death doulas are important?

Jane Whitlock: A doula helps ask the big questions so this process is as spiritually comforting as it can be. Think of your deathbed and how you want to feel—at peace, right? So, how do you get there?

A doula also gives you some sense of what’s coming and can support you through these tough situations that you may not be prepared for. You haven’t been here before and often don’t have any bank of knowledge to draw from.

Cultures have evolved to include how we care for people who are dying and have died, and while some intact cultures can trace their beliefs back very far (to the Buddha, for example), Americans don’t have those deep ties.

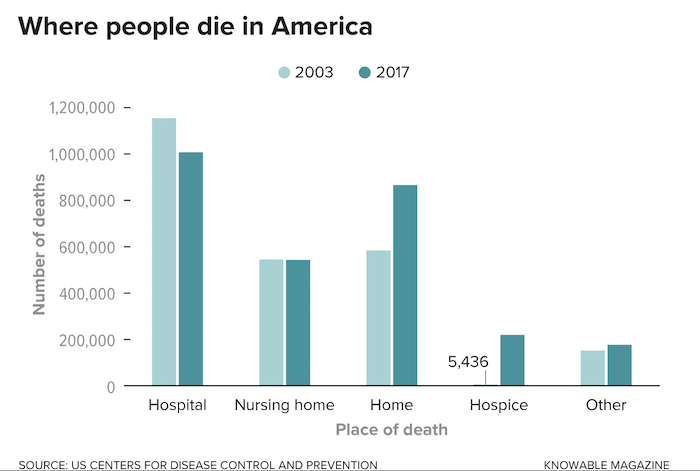

Since the Civil War, the standardization of funeral homes, embalming, and the medicalization of end-of-life have removed death from the home. We no longer know how to care for people who are dying, how to have home vigils, how to mark significant transition points (leaving a body for the last time, a body leaving the house).

How can our modern standardized systems shift to accommodate what death doulas have to offer?

It would be amazing if hospitals employed doulas! Wouldn’t it be great if you could transfer someone who has died to a room to clean them up, bring the family in, and have someone guide them through rituals of saying goodbye and nurturing the body?

I think a lot of times this seems like a white lady movement—like, we want to cover everything in crystals and candles and aromatherapy or whatever. I push pack against that because there are so many other ways of experiencing death. This movement needs to be more inclusive, to change a whole bunch; being a death doula is a teeny, tiny door, and there is a lot of growth ahead.

What characteristics make an effective death doula?

You have to be able to empty yourself out, to be hollow and free of judgment, of any preconceived ideas about what should be happening. You have to listen without thinking and really be with someone when they’re suffering without trying to fix it. An effective death doula is someone who is calm, quiet, and vulnerable. It’s really so much about vulnerability.

I volunteer at a hospice and often have to practice that whole “soft belly” thing, to stop before every room and become wide open. Even when someone doesn’t want to see you, you have to think, “It’s not about me.” You just kind of clear your energy, go into the next door. You have to fight being defensive in order to just be vulnerable.

What are some ways to go about changing our death culture?

It really starts with your stories. We don’t tell our death stories; we tell our birth stories and our family stories, but we don’t tell our death stories. It would be great to just listen to a bunch of stories about how it happens, maybe know just some weird and messy stuff, too. What was it like? What would you have done differently? What went well? What surprised you?

There’s this guy, Dr. Allan Kellehear, who says our inability to talk about death is a public health epidemic. He refers to the AIDS epidemic and how you couldn’t shut a bathroom stall without a poster on the back teaching about prevention and safety. Wouldn’t it be great if we took that type of vast approach to shifting death culture?

Another maverick in the field, Suzanne O’Brien of Doulagivers, says there should be someone on every block who knows the end-of-life basics so that when somebody in your community is dying, they are supported.

Who do you think is the best at approaching death?

Well, the Buddhists, hands down. They’ve got the saying: “We are of the nature to get old; we are of the nature to suffer; we are of the nature to die.” Imagine if that’s how we started every morning—we wouldn’t be so shocked by death! There are people who think that aging is some kind of radical punishment or who feel entitled to live in a full healthy body forever. That’s just not our nature.

I would say that to prepare for death, you have to get your spiritual house in order, whatever that means to you. Life is finite, super fragile, and you are not entitled to anything! So, spend your time wisely and be grateful.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!