by FREDERICK S. PAXTON

In the world in which Christianity emerged, death was a private affair. Except when struck down on the battlefield or by accident, people died in the company of family and friends. There were no physicians or religious personnel present. Ancient physicians generally removed themselves when cases became hopeless, and priests and priestesses served their gods rather than ordinary people. Contact with a corpse caused ritual impurity and hence ritual activity  around the deathbed was minimal. A relative might bestow a final kiss or attempt to catch a dying person’s last breath. The living closed the eyes and mouth of the deceased, perhaps placing a coin for the underworld ferryman on the tongue or eyelids. They then washed the corpse, anointed it with scented oil and herbs, and dressed it, sometimes in clothing befitting the social status of the deceased, sometimes in a shroud. A procession accompanied the body to the necropolis outside the city walls. There it was laid to rest, or cremated and given an urn burial, in a family plot that often contained a structure to house the dead. Upon returning from the funeral, the family purified themselves and the house through rituals of fire and water.

around the deathbed was minimal. A relative might bestow a final kiss or attempt to catch a dying person’s last breath. The living closed the eyes and mouth of the deceased, perhaps placing a coin for the underworld ferryman on the tongue or eyelids. They then washed the corpse, anointed it with scented oil and herbs, and dressed it, sometimes in clothing befitting the social status of the deceased, sometimes in a shroud. A procession accompanied the body to the necropolis outside the city walls. There it was laid to rest, or cremated and given an urn burial, in a family plot that often contained a structure to house the dead. Upon returning from the funeral, the family purified themselves and the house through rituals of fire and water.

Beyond such more or less shared features, funeral rites, as well as forms of burial and commemoration, varied as much as the people and the ecology of the region in which Christianity developed and spread. Cremation was the most common mode of disposal in the Roman Empire, but older patterns of corpse burial persisted in many areas, especially in Egypt and the Middle East. Christianity arose among Jews, who buried their dead, and the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus were its defining events. Although Christians practiced inhumation (corpse burial) from the earliest times, they were not, as often assumed, responsible for the gradual disappearance of cremation in the Roman Empire during the second and third centuries, for common practice was already changing before Christianity became a major cultural force. However, Christianity was, in this case, in sync with wider patterns of cultural change. Hope ofsalvation and attention to the fate of the body and the soul after death were more or less common features of all the major religious movements of the age, including the Hellenistic mysteries, Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism, Manichaeanism, and Mahayana Buddhism, which was preached as far west as Alexandria.

Early Christian Responses to Death and Dying

In spite of the centrality of death in the theology and spiritual anthropology of early Christians, they were slow to develop specifically Christian responses to death and dying. The most immediate change was that Christians handled the bodies of the dead without fear of pollution. The purification of baptism was permanent, unless marred by mortal sin, and the corpse of a Christian prefigured the transformed body that would be resurrected into eternal life at the end of time. The Christian living had less need than their neighbors to appease their dead, who were themselves less likely to return as unhappy ghosts. Non-Christians noted the joyous mood at Christian funerals and the ease of the participants in the presence of the dead. They observed how Christians gave decent burials to even the poorest of the poor. Normal Roman practice was to dump them in large pits away from the well-kept family tombs lining the roads outside the city walls.

The span of a Christian biography stretched from death and rebirth in baptism, to what was called the “second death,” to final resurrection. In a sense, then, baptism was the first Christian death ritual. In the fourth century Bishop Ambrose of Milan (374–397) taught that the baptismal font was like a tomb because baptism was a ritual of death and resurrection. Bishop Ambrose also urged baptized Christians to look forward to death with joy, for physical death was just a way station on the road to paradise. Some of his younger contemporaries, like Augustine of Hippo, held a different view. Baptism did not guarantee salvation, preached Augustine; only God could do that. The proper response to death ought to be fear—of both human sinfulness and God’s inscrutable judgment.

This more anxious attitude toward death demanded a pastoral response from the clergy, which came in the form of communion as viaticum (provisions for a journey), originally granted to penitents by the first ecumenical council at Nicea (325), and extended to all Christians in the fifth and sixth centuries. There is, however, evidence that another type of deathbed communion was regularly practiced as early as the fourth century, if not before. The psalms, prayers, and symbolic representations in the old Roman death ritual discussed by the historian Frederick Paxton are in perfect accord with the triumphant theology of Ambrose of Milan and the Imperial Church. The rite does not refer to deathbed communion as viaticum, but as “a defender and advocate at the resurrection of the just” (Paxton 1990, p. 39). Nor does it present the bread and wine as provisions for the soul’s journey to the otherworld, but as a sign of its membership in the community of the saved, to be rendered at the last judgment. Thanks, in part, to the preservation and transmission of this Roman ritual, the Augustinian point of view did not sweep all before it and older patterns of triumphant death persisted.

However difficult the contemplation (or moment) of death became, the living continually invented new ways of aiding the passage of souls and maintaining community with the dead. In one of the most important developments of the age, Christians began to revere the remains of those who had suffered martyrdom under Roman persecution. As Peter Brown has shown, the rise of the cult of the saints is a precise measure of the changing relationship between the living and the dead in late antiquity and the early medieval West. The saints formed a special group, present to both the living and the dead and mediating between and among them. The faithful looked to them as friends and patrons, and as advocates at earthly and heavenly courts. Moreover, the shrines of the saints brought

people to live and worship in the cemeteries outside the city walls. Eventually, the dead even appeared inside the walls, first as saints’ relics, and then in the bodies of those who wished to be buried near them. Ancient prohibitions against intramural burials slowly lost their force. In the second half of the first millennium, graves began to cluster around both urban and rural churches. Essentiallycomplete by the year 1000, this process configured the landscape of Western Christendom in ways that survive until the present day. The living and the dead formed a single community and shared a common space. The dead, as Patrick Geary has put it, became simply another “age group” in medieval society.

Emergence of a Completely Developed Death Ritual in the Medieval Latin Church

However close the living and dead might be, it was still necessary to pass from one group to the other, and early medieval Christians were no less inventive in facilitating that passage. The centuries from 500 to 1000 saw the emergence of a fully developed ritual process around death, burial, and the incorporation of souls into the otherworld that became a standard for Christian Europeans until the Reformation, and for Catholics until the very near present. The multitude of Christian kingdoms that emerged in the West as the Roman Empire declined fostered the development of local churches. In the sixth, seventh, and eighth centuries, these churches developed distinctive ritual responses to death and dying. In southern Gaul, Bishop Caesarius of Arles (503–543) urged the sick to seek ritual anointing from priests rather than magicians and folk healers and authored some of the most enduring of the prayers that accompanied death and burial in medieval Christianity. Pope Gregory the Great (590–604) first promoted the practice of offering the mass as an aid to souls in the afterlife, thus establishing the basis for a system of suffrages for the dead. In seventh-century Spain, the Visigothic Church developed an elaborate rite of deathbed penance. This ritual, which purified and transformed the body and soul of the dying, was so powerful that anyone who subsequently recovered was required to retire into a monastery for life. Under the influence of Mosaic law, Irish priests avoided contact with corpses. Perhaps as a consequence, they transformed the practice of anointing the sick into a rite of preparation for death, laying the groundwork for the sacrament of extreme unction. In the eighth century, Irish and Anglo-Saxon missionary monks began to contract with one another for prayers and masses after death.

All of these developments came into contact in the later eighth and ninth centuries under the Carolingian kings and emperors, especially Charlemagne (769–814), but also his father Pepin and his son Louis. Together they unified western Europe more

successfully around shared rituals than common political structures. The rhetoric of their reforms favored Roman traditions, and they succeeded in making the Mass and certain elements of clerical and monastic culture, like chant, conform to Roman practice whether real or imagined. When it came to death and dying, however, Rome provided only one piece of the Carolingian ritual synthesis: the old Roman death ritual. Whether or not it was in use in Rome at the time, its triumphant psalmody and salvation theology struck a chord in a church supported by powerful and pious men who saw themselves as heirs to the kings of Israel and the Christian emperors of Rome. Other elements of their rituals had other sources. Carolingian rituals were deeply penitential, not just because of Augustine, but also because, in the rough-and-tumble world of the eighth and ninth centuries, even monks and priests were anxious about making it into heaven. Although reformers, following Caesarius of Arles, promoted the anointing of the sick on the grounds that there was no scriptural basis for anointing the dying, deathbed anointing came into general use, often via Irish texts and traditions. Carolingian rituals also drew liberally on the prayers of Caesarius of Arles and other fathers of the old Gallican and Visigothic churches.

The ritual experts of the Carolingian age did not just adapt older rites and provide a setting for their synthesis, however; they made their own contributions as well. In his classic 1908 study on ritual, the anthropologist Arnold van Gennep was surprised by the lack of elaboration of the first phase of death rites in the ethnographic reports he studied. People generally ritualized burial and commemoration, but gave little attention to the dying. Unlike other rites of passage, few rituals prepared people for death. Familiarity with European Christian traditions may be the source of van Gennep’s surprise, for well-developed preliminal rites are one of their most characteristic features. Around the year 800 certain clerical communities introduced a ritual for the death agony. To aid the dying through the struggle of the soul’s exit from the body, the community chanted the names of the denizens of paradise. Rhythmically calling on the Trinity, Mary, the angels, the prophets and patriarchs, the martyrs and confessors, and all living holy men and women, they wove a web of sung prayer to aid the soul’s passing. This practice quickly became part of a common tradition that also included rites of penance, absolution, anointing, and communion, each of which helped cut the ties that bound the dying to this world, ritually preparing them for entry into paradise.

Like most human groups, Christians had always used rites of transition to allay the dangers of the liminal period after death before the corpse was safely buried and the soul set on its journey to the otherworld. The same was true of post-liminal rites of incorporation, which accompanied the body into the earth, the soul into the otherworld, and the mourners back into normal society. But medieval Christians placed the ritual commemoration of the dead at the very center of social life. Between 760 and 762, a group of churchmen at the Carolingian royal villa of Attigny committed themselves to mutual commemoration after death. Not long afterward, monastic congregations began to make similar arrangements with other houses and with members of secular society. They also began to record the names of participants in books, which grew to include as many as 40,000 entries. When alms for the poor were added to the psalms and masses sung for the dead, the final piece was in place in a complex system of exchange that became one of the fundamental features of medieval Latin Christendom. Cloistered men and women, themselves “dead to this world,” mediated these exchanges. They accepted gifts to the poor (among whom they included themselves) in exchange for prayers for the souls of the givers and their dead relatives. They may have acted more out of anxiety than out of confidence in the face of death, as the scholar Arno Borst has argued, but whatever their motivations, their actions, like the actions of the saints, helped bind together the community of the living and the dead.

Like most human groups, Christians had always used rites of transition to allay the dangers of the liminal period after death before the corpse was safely buried and the soul set on its journey to the otherworld. The same was true of post-liminal rites of incorporation, which accompanied the body into the earth, the soul into the otherworld, and the mourners back into normal society. But medieval Christians placed the ritual commemoration of the dead at the very center of social life. Between 760 and 762, a group of churchmen at the Carolingian royal villa of Attigny committed themselves to mutual commemoration after death. Not long afterward, monastic congregations began to make similar arrangements with other houses and with members of secular society. They also began to record the names of participants in books, which grew to include as many as 40,000 entries. When alms for the poor were added to the psalms and masses sung for the dead, the final piece was in place in a complex system of exchange that became one of the fundamental features of medieval Latin Christendom. Cloistered men and women, themselves “dead to this world,” mediated these exchanges. They accepted gifts to the poor (among whom they included themselves) in exchange for prayers for the souls of the givers and their dead relatives. They may have acted more out of anxiety than out of confidence in the face of death, as the scholar Arno Borst has argued, but whatever their motivations, their actions, like the actions of the saints, helped bind together the community of the living and the dead.

The Carolingian reformers hoped to create community through shared ritual, but communities shaped ritual as much as ritual shaped communities, and the synthesis that resulted from their activities reflected not just their official stance but all the myriad traditions of the local churches that flowed into their vast realm. By the end of the ninth century a ritual process had emerged that blended the triumphant psalmody of the old Roman rites with the concern for penance and purification of the early medieval world. A rite of passage that coordinated and accompanied every stage of the transition from this community to the next, it perfectly complemented the social and architectural landscape. Taken up by the reform movements of the tenth and eleventh centuries, this ritual complex reached its most developed form at the Burgundian monastery of Cluny. At Cluny, the desire to have the whole community present at the death of each of its members was so great that infirmary servants were specially trained to recognize the signs of approaching death.

The Modern Age

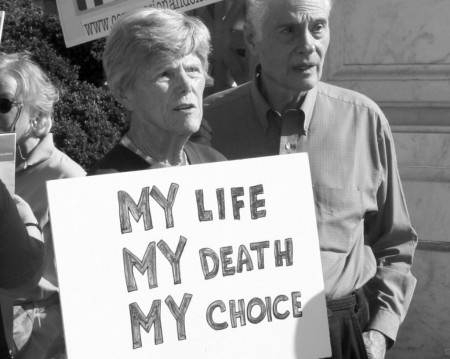

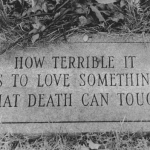

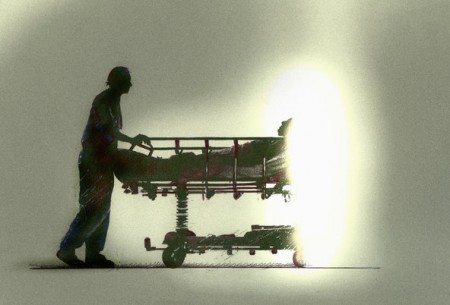

Christian death rituals changed in the transition to modernity, historians like Philippe Ariès and David Stannard have detailed in their various works. But while Protestants stripped away many of their characteristic features, Catholics kept them essentially the same, at least until the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). Like the Carolingian reformers, the fathers of Vatican II moved to restrict ritual anointing to the sick, but they may be no more successful in the long run, for the symbolic power of anointing as a rite of preparation for death seems hard to resist. And while the secularization of society since the 1700s has eroded the influence of Christian death rites in Western culture, nothing has quite taken their place. Modern science and medicine have taught humankind a great deal about death, and about how to treat the sick and the dying, but they have been unable to give death the kind of meaning that it had for medieval Christians. For many people living in the twenty-first century death is a wall against which the self is obliterated. For medieval Christians it was a membrane linking two communities and two worlds. In particular, Christian rites of preparation for death offered the dying the solace of ritual and community at the most difficult moment in their lives.

Reconnecting with the Past

The Chalice of Repose Project at St. Patrick Hospital in Missoula, Montana, is applying ancient knowledge to twenty-first-century end-of-life care. Inspired in part by the medieval death rituals of Cluny, the Chalice Project trains professional music thanatologists to serve the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of the dying with sung prayer. With harp and voice, these “contemplative musicians” ease the pain of death with sacred music—for the dying, but also for their families and friends and for the nurses and doctors who care for them. While anchored in the Catholic tradition, music thanatologists seek to make each death a blessed event regardless of the religious background of the dying person. Working with palliative physicians and nurses, they offer prescriptive music as an alternative therapy in end-of-life care. The Chalice of Repose is a model of how the past can infuse the present with new possibilities.

The Chalice of Repose Project at St. Patrick Hospital in Missoula, Montana, is applying ancient knowledge to twenty-first-century end-of-life care. Inspired in part by the medieval death rituals of Cluny, the Chalice Project trains professional music thanatologists to serve the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of the dying with sung prayer. With harp and voice, these “contemplative musicians” ease the pain of death with sacred music—for the dying, but also for their families and friends and for the nurses and doctors who care for them. While anchored in the Catholic tradition, music thanatologists seek to make each death a blessed event regardless of the religious background of the dying person. Working with palliative physicians and nurses, they offer prescriptive music as an alternative therapy in end-of-life care. The Chalice of Repose is a model of how the past can infuse the present with new possibilities.

Complete Article HERE!

I was trained to use highly sophisticated tools to rescue those even beyond the brink of death. But I was never trained how to unhook these tools. I never learned how to help my patients die. I committed the protocols of lifesaving to memory and get recertified every two years to handle a Code Blue, which alerts us to the need for immediate resuscitation. Yet a Code Blue is rarely successful. Very few patients ever leave the hospital afterward. Those that do rarely wake up again.

I was trained to use highly sophisticated tools to rescue those even beyond the brink of death. But I was never trained how to unhook these tools. I never learned how to help my patients die. I committed the protocols of lifesaving to memory and get recertified every two years to handle a Code Blue, which alerts us to the need for immediate resuscitation. Yet a Code Blue is rarely successful. Very few patients ever leave the hospital afterward. Those that do rarely wake up again.