By Steve Lopez

When my mother was dying, a private, for-profit hospice agency failed her — the assigned nurse was late for the first visit because of a staffing shortage. My mother suffered in misery without pain medication, and our family dumped the agency and switched to a nonprofit.

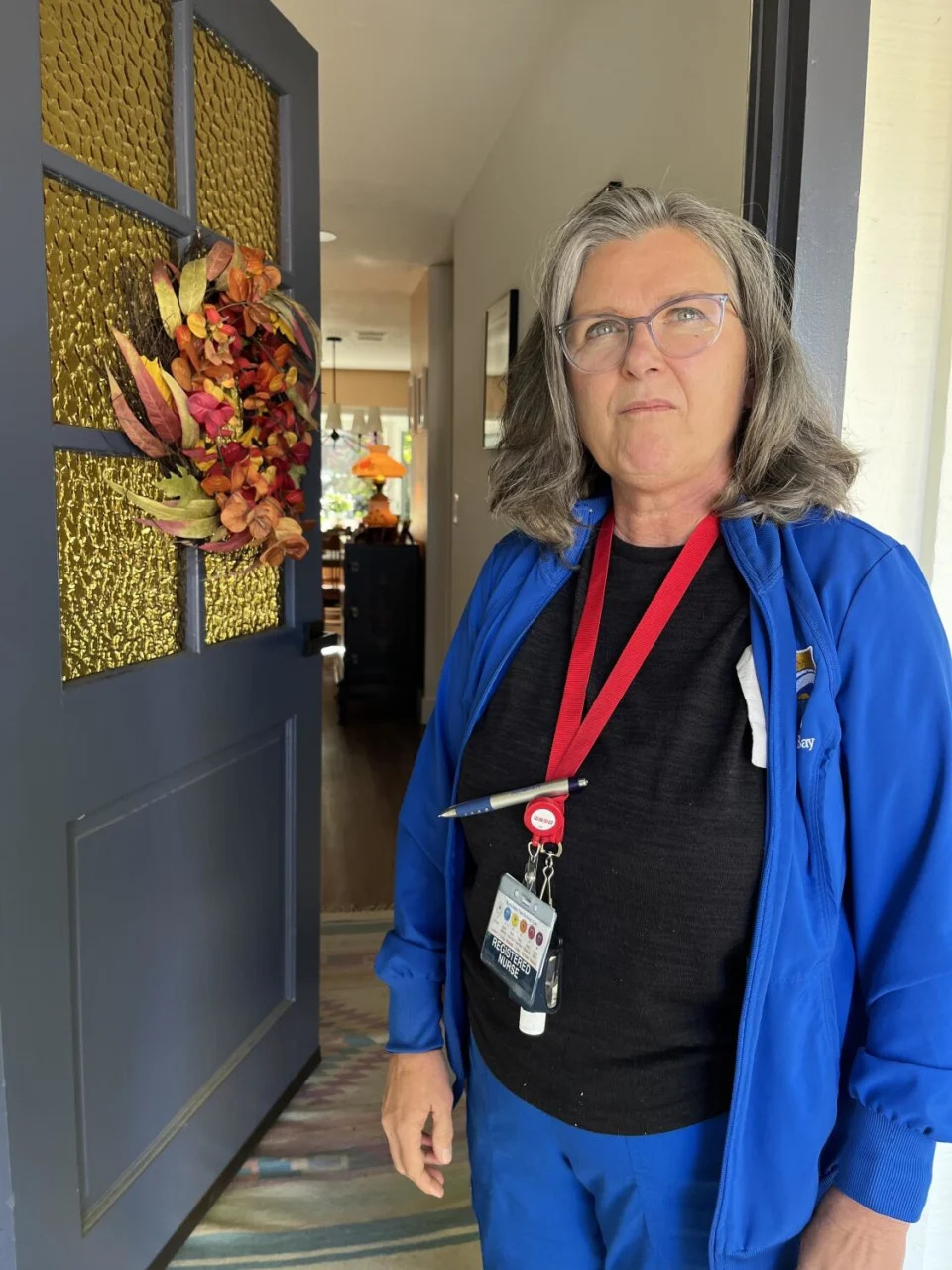

Karen Eshelman was the nurse who came to the rescue, calmly and quickly adjusting the pain medication and compassionately preparing us for the inevitable. Grace Lopez died peacefully a couple of days later, just shy of 90.

Eshelman showed up at my mother’s funeral to pay her respects, and recently, almost five years later, I dropped by her home in Concord to say thanks.

“For a lot of us in hospice care, something happened in life that made us want to give back,” Eshelman told me in her kitchen, wearing her blue uniform as she got ready for another shift. She said she lost her first husband when she was 30, and with their two kids to care for, she had to learn how to confront death and move past it.

“I know families will get through it,” said Eshelman, who remarried 25 years ago. “Grief isn’t easy, but you will come out on the other side and have good things happen in life.”

Demand for hospice care will grow dramatically as the population ages, but staff shortages, corporate profiteering and a rash of Medicare fraud and billing scandals have roiled the industry, with recent exposes in the L.A. Times and a joint ProPublica-New Yorker investigation. For a time, nonprofits resisted those trends, but Eshelman surprised me with a news flash.

She and her colleagues at Hospice East Bay had just voted to join the National Union of Healthcare Workers because they felt that industry pressures had begun to hit their agency. Eshelman said the big issue wasn’t money, but a belief that staffing shortages were impacting the quality of care.

“It leads to nurses being burned out, and not just nurses, but social workers and spiritual care counselors,” Eshelman said. “And it leads to more people calling in sick because they just need a break and they need a day off.”

Nearly 400 employees at five Bay Area nonprofit hospice agencies have joined the same union since May 2022, mirroring organizing efforts at hospice agencies in several other states.

Sal Rosselli, president of NUHW, said the corporatization of what had been primarily a faith-based, community-oriented, charitable industry has led to “an increasing drive to focus on the bottom line as opposed to providing adequate care or taking care of healthcare workers.”

When you’re holding the hand of a loved one who’s dying, you’ve got a lot on your mind, but it’s not the hospice agency’s bottom line you’re thinking about.

Some hospice employees “are being told they only have 30 minutes with a patient,” said Richard Draper, NHWU’s director of organizing, even though depending on the level of care needed, a patient might need far more attention. “The major issue for us is staffing,” Draper said, “and being able to have a voice in how the care is delivered.”

Jessica Williams is a registered nurse at the nonprofit Providence Hospice Sonoma County, where 131 employees organized in February. “I think ‘nonprofit’ is really only a name,” said Williams, who got into hospice care after her mother died in a car accident and she attended a grief support service at a hospice agency. She said a layoff and the scaling back of visits by home health aides “makes it more difficult for us to do a good job out there,” even as executives in the agency’s parent organization pocket millions in compensation.

The director of her hospice agency didn’t respond to my interview request, but I checked the ProPublica log of nonprofit tax records, in which the tax-exempt St. Joseph Providence Health — one of the nation’s largest nonprofit healthcare companies — listed its mission as being “steadfast in serving all, especially those who are poor and vulnerable.” For the 2021 tax year, according to the log, company Chief Executive Rod Hochman pocketed more than $10 million and was one of 11 executives at the company making above $1 million.

This is a nonprofit?

Claire Eustace, a spiritual care clinician at Hospice East Bay, said her job is made more difficult when the nursing team is understaffed and overworked, and there have been times when nurses had to work 10 straight days.

“It affects my work in that … loved ones are upset because they’re not getting the support they need,” Eustace said.

“We were being stretched too far and couldn’t provide good care and were getting burned out,” said her colleague Andrea Hurley, a social worker. Caseloads for social workers went from 26 to 30 and more, Hurley said, which can still be manageable except that shortages for other job categories were mounting.

“In previous years, I felt like the leadership would hear us and there could be some changes,” Hurley said.

Bill Musick, interim CEO of Hospice East Bay, said his staffing-per-patient levels are among the highest in the industry, but he conceded the agency is on the edge of a cliff financially. He’s down several nurses, he said, because it’s hard to fill positions given a healthcare labor shortage. So he’s been using contracted traveling nurses.

“Medicare reimbursement rates have increased slightly over the years, but they’ve not kept up with inflation and the increase in wages,” Musick said. “And so year after year, we’re trying to figure out what we can cut in order to stay in business.”

Holding onto legacy traditions like grief counseling isn’t easy, Musick said, and he predicts consolidation. But a recent plan to merge Hospice East Bay with another nonprofit fell through.

People can have good experiences in for-profit hospice care and bad ones in nonprofits, said Jennifer Moore Ballentine, chief executive of the advocacy and policy group Coalition for Compassionate Care of California. In general, she said, “nonprofits have better quality metrics and are doing a better job,” but they are struggling to stay afloat.

“Frankly, it’s a mess,” Ballentine said. “I weep every day for the industry that was hospice because I think it really is in trouble.”

In the hospice industry, and in the nursing home field as well, the provider network became inundated by equity and real estate investors, among other opportunists without a shred of experience in healthcare. Given the inevitability of chronic illness and end-of-life care, they flocked like vultures, eager to cash in.

California has cracked down on hospice agency proliferation following The Times expose, but greater regulation and oversight at the federal level is imperative. Dr. Joan Teno, a Brown University authority on the industry, called for a raft of reforms in a JAMA article published in May.

“The need for change is urgent to ensure that frail, older people receive high-quality care and that fraudulent care is rooted out of the system,” Teno wrote. “Quality measures are important, but there is a need to improve integrity oversight. The time is now.”

Ballentine said anyone shopping for a hospice agency should take a look at the national hospice locator, which compiles data on agency quality. When I checked Bay Area listings, Hospice East Bay was at the top.

It’s worth noting that when I spoke to my mother’s nurse and her colleagues, they told me that despite their grievances, they want to stick with their employer.

“I moved here because I love this agency and think it’s really good,” said Eshelman, who’s from the Midwest. Unionizing, she said, was a way for employees to have a bigger voice in upholding the traditions of the nonprofit model.

The ultimate goal, she said, “is to provide even better patient care.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!