Study finds that seriously ill young people want to discuss their care, wishes — Barbara Brotman

It is the hardest conversation a parent can imagine: talking to a critically ill child about the possibility of death.

But Deb Fuller, of Woodstock, wishes she had done it sooner.

By the time she and her husband broached the subject with their nearly 13-year-old daughter, Hope, her brain cancer was so advanced that she could barely speak.

By the time she and her husband broached the subject with their nearly 13-year-old daughter, Hope, her brain cancer was so advanced that she could barely speak.

Fuller asked Hope if she was afraid; if she was worried about how her parents and brother would cope when she was gone; if she was ready to go anyway.

Hope answered by squeezing her mother’s hand: Yes. Yes. And yes.

“That ended up being one of the best nights we had,” Fuller said. “We all sat around together to the wee hours of the morning and talked.

“But I waited too long. I thought we had more time,” she said.

Hope died within days.

“I wish she could have spoken to me,” she said. “I hate the thought that perhaps she laid there … and worried about it, unable to talk to me about it.”

End-of-life experts say that children should have the opportunity to discuss death in a developmentally appropriate way with a parent or a knowledgeable adult, though such conversations should not be forced.

And a recent study shows that many seriously ill children want to have that talk, and that both they and their parents are relieved afterward.

But parents often don’t know how to begin an end-of-life conversation with their children, said Maureen Lyon, associate research professor in pediatrics at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington and principal investigator at its Children’s Research Institute.

They are often afraid that talking about death will be harmful to the child, Lyon said. And by the time teenagers enter hospice or palliative care programs, which are adept at such conversations, the youths may be too ill to be able to talk or not want to at all.

But it can be a crucial conversation, Lyon said. Important decisions may have to be made, like whether to discontinue aggressive medical treatment or whether they would want to die at home or in a hospital.

Too often, no one — not even doctors — asks these questions of seriously ill teenagers themselves, she said. Without knowing their children’s wishes, families can be torn apart by conflict. And though youths under 18 have no legal standing to direct their medical care, Lyon said, their opinions should be heard.

She and Linda Briggs, associate director of the Respecting Choices program at Gunderson Health System in La Crosse, Wis., designed a way they can be.

They conducted a study in which they used facilitators to guide seriously ill young people and their families through conversations about end-of-life care — the same kind of conversations Respecting Choices offers to adults. At the end, the teens filled out advance directives outlining their wishes.

The study, which Lyon and Briggs presented at the annual conference of the International Society of Advance Care Planning and End of Life Care held recently in Rosemont, found that the youths wanted to be consulted, parents wanted to know their children’s thoughts and both teenagers and their families found the experience worthwhile.

Moreover, the conversations did not cause harm. The young people — who were between 14 and 21 and had either HIV or cancer — were no more anxious and depressed after they talked.

“The assumption is that these conversations will take away hope and raise anxiety. The reality is the opposite,” Briggs said.

Not that the conversations were entirely pain-free.

“The study was much harder on the teens with cancer,” Lyon said. A small percentage of those youths said they had found the talks hurtful. However, they also found them worthwhile. Lyon hypothesized that because they were more ill than the HIV-positive youths, the possibility of death was more real.

But Jessica Gaines, 22, who participated in the study as an 18-year-old who had been treated for Hodgkin lymphoma, said she was glad to be finally asked her opinion.

“When I was going through treatment, I was never asked, ‘Well, what happens if you don’t make it through?'” said Gaines, who lives outside Washington.

Parents were appreciative of the talks too. “I feel like a load was lifted,” one commented in a survey.

Some teens and families declined to participate. Hospices, too, find that not everyone wants to have such talks.

Jeremy Campus, 13, of the Northwest Side, is battling cancer that has recurred a third time. A patient at Hospice and Palliative Care of Northeastern Illinois, Jeremy is well aware of the gravity of his condition. His mother, Annmarie, has let him know that she is available to talk about anything, and his palliative care team is similarly open.

But when it comes to addressing the worst possibility, the quiet-voiced boy sitting at his family’s dining room table is clear.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” he said.

Some parents don’t want their children to talk about it.

“I was against, until the last breath of my son, for anybody to even to mention the word death to him,” said Alla Lyubyezny, of Buffalo Grove, whose son, Max Stine, died of brain cancer five years ago. He was 17 and a patient at Horizon Hospice and Palliative Care.

She didn’t want Max to lose hope, and considered it her duty to protect him from the pain of confronting death.

“Nobody needs to have this information, and to live their last, the month of time that is left to them, with that,” she said. “There are some subjects that are best left alone.”

But children generally know how sick they are, said Jennifer Misasi, head of Horizon’s pediatric program. They sometimes avoid talking about it to protect their parents, she said.

And there is no evidence that talking about impending death in a sensitive and appropriate way takes away children’s or parents’ hope or leaves them devastated, said Dr. David Steinhorn, medical director of the palliative care program at Chicago’s Lurie Children’s Hospital.

“Parents who have the opportunity to have frank conversations in a supportive, open way actually do much better and have fewer regrets when their child is dead than parents who do not talk about it,” he said.

“We’re not saying this should be imposed on anybody,” Lyon said. “But for those teens that want to have a voice, this works.”

“This isn’t about ‘Do you want CPR, yes or no,'” Briggs said. “It’s having them express their goals and values.

“How would you want your mom to make decisions for you? What would you want your mom to know about what kind of life makes sense to you, and what kind of life doesn’t make sense to you?”

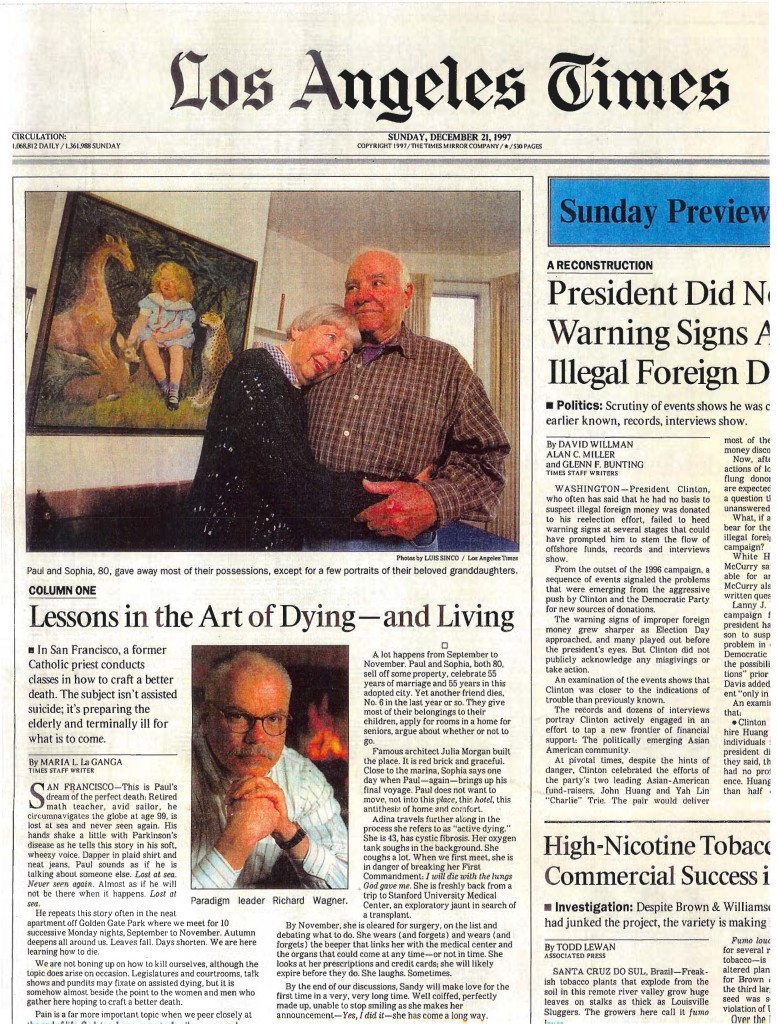

Complete Article HERE!