When the California Medical Association removed its long-standing objection to assisted death in May, it seemed to clear a legislative path for Senate Bill 128, which would allow physicians to provide lethal drugs to patients with less than six months to live.

But the powerful doctors group’s neutral position has not quelled the controversy, either among lawmakers or in the medical community. After passing the state Senate last month, SB 128 could meet its end during a hearing Tuesday in the Assembly Health Committee, where it stalled two weeks ago over growing objections from Latino Democrats.

Nearly 18 years after Oregon enacted the country’s first assisted-death law, doctors also remain strongly divided over the ethics of the policy. Does it provide patients with a personal choice to end their suffering, or violate a physician’s oath to do no harm? The answer can be deeply personal.

Pro: ‘We treat our pets better than we treat our loved ones’

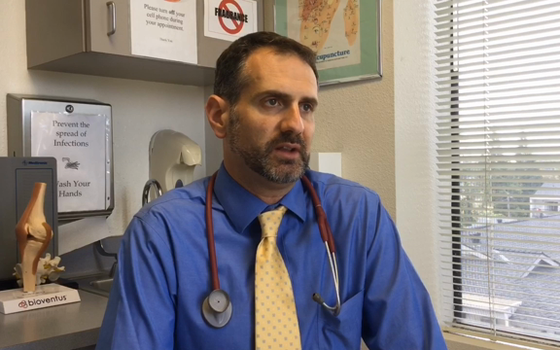

Dr. Michael Amster, a pain-management specialist in Fairfield, deals with dying patients every day.

But he was unfamiliar with assisted death before last year, when a college friend who lived in Oregon came to the end of a debilitating two-year battle with gynecological cancer. As his friend considered taking advantage of the state’s law, Amster said she found a “peace of mind knowing that she could end her suffering if it got too unbearable.”

“She shared that, because of that, she was able to live her life more fully in the present moment and not worry about the future and the unknowns,” Amster said. Though his friend died too quickly to use Oregon’s law, “watching what she went through woke me up to understanding the value of having this option available in the end-of-life process.”

Amster has since become an advocate for assisted death in California, urging lawmakers to pass SB 128. He sees it as an issue of personal choice and autonomy in health care, rather than as physicians assisting patients to commit suicide, as some opponents have framed it.

“All it does is hasten a natural process,” he said.

Opponents have pointed to existing palliative care and pain management options as better ways to help dying patients in their final days. But Amster said available medications don’t work for everyone or can provide a poor quality of life, leaving people delirious and sedated.

He draws a contrast between sick animals, who are put down when their suffering becomes too great, and people, who are left to ride out the natural course of their dying process until their bodies finally shut down.

“We treat our pets better than we treat our loved ones, is what it comes down to,” he said. “There needs to be another option for people that are really stuck and suffering greatly.”

If SB 128 becomes law, Amster would be open to prescribing the medication. He said he already has those conversations with patients who come to him seeking help in dying, but he has to be “clear with them the boundaries” about what is legal.

That hit home last year as another friend of Amster’s in Davis was dying of ovarian cancer. She explored the possibility of moving to Oregon, but didn’t have enough time left to establish residency, so she began to talk about ending her own life in a “ritual” surrounded by loved ones.

“I watched my friend and her husband horrified and scared about, you know, if she chose to take all of her hospice medication and overdose and die, like, could he be thrown in jail if he knew about this?” Amster said.

When his friend began consulting Amster about how she might overdose, he said he had to make the difficult decision to distance himself.

“As a friend and someone who loved her, I wanted to help her end her suffering,” he said. “But ethically and with my license and what I felt what was the right thing, there was nothing I could do to help her.”

Amster hopes that legalizing assisted death in California will bring those conversations about dying into the open, and get people thinking about their own wishes.

“What are our values? What do we consider humane treatment for someone who’s at the end of their life?” he said. “Is that really suicide, or is that compassion?”

Con: Focus on improving hospice care

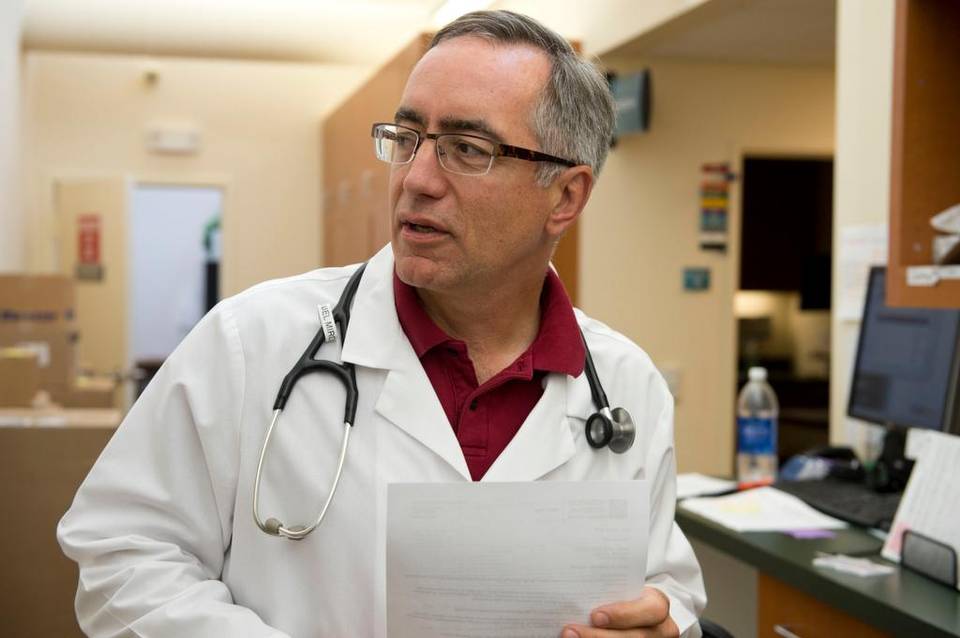

Dr. Daniel Mirda, a hematology and oncology specialist in Napa, tries to take the fear out of cancer treatment.

“I can’t tell you how many times a person comes to me and they’re very afraid of their illness and they’re facing a lot of possible disasters,” he said. “Yet oftentimes having a plan simplifies their life, helps them deal with it and better understand what to do.”

He takes the same approach with SB 128, which he has testified against as president of the Association of Northern California Oncologists.

While Mirda understands why someone facing a lethal and debilitating illness might want to “head it off at the pass,” he sees his role as providing patients with the best options possible for living their “most productive life” going forward.

“I don’t think in the same sitting I can tell you how to fight your cancer and this is how you end the fight,” he said.

Mirda shares some of the ethical concerns that other opponents of assisted death have expressed: Would the socioeconomically challenged be more likely to choose this option because medical therapies are too expensive? How much sway would a patient’s family have over their decision? Would it be overused?

He also objects to cutting short the process of dying, which he believes can be an important time for patients and their families.

“When you first find out you have an illness, the last thing you want to do is kill yourself,” Mirda said. Then as time goes on and people deal with the consequences, they can assess their quality of life and decide whether to keep seeking treatment.

“This idea of getting ready for death is sometimes as valuable to people as doing therapy to avoid it,” he said. “How are you going to spend that time that you have left?”

For loved ones, there’s a chance to say goodbye.

Mirda’s mother-in-law died from acute leukemia last month. At first, he said, the family wanted her to live longer. But as she developed various complications from the cancer, everyone was integrated into her struggle and eventually understood that she could no longer keep fighting it.

He compares it to his father’s sudden death many years ago, which left him in the lurch. When his mother-in-law finally died, the family was “kind of at peace.”

“You have done everything possible to help this individual,” he said. “There are no regrets at all.”

Mirda would rather that California focus on improving hospice care, which he regards as a “totally supportive environment” for both dying patients and those they are leaving behind.

“That to me is really where the real effort would have to be exerted – respecting the individual, but then respecting who this is going to affect that moves on,” he said.

If lawmakers pass SB 128, however, Mirda said he would at least make sure that his patients are informed of their options and free to choose for themselves. Whether he could prescribe the medication himself may depend on his relationship with the patient who asks.

“Could I do that if faced with it? We’ll have to see,” he said. “It would almost have to be as individual as the decision itself.”

Complete Article HERE!