Tips on how to guide little hearts through their grief to help them deal with their loss and recover from it

By Jennifer Walker

[S]aying goodbye to a pet is an inevitable experience many families will experience.

And telling the truth to children and allowing them to grieve is crucial in helping them deal with their loss, as well as recover from it.

“I think it is important to tell children the truth but depending on their age and developmental level, the information you communicate will differ,” said Kyle Newstadt, individual and family therapist and director of Integrate Health Services. “Regardless, they should know the truth and if you know the pet is sick or death is on the horizon, it is important to communicate that with children.”

According to Ms. Newstadt, books can be helpful to introduce the topic to a child with the family without any other distractions. She said parents could explain to their children that the animal has been to the doctor for medicine and that they’re waiting to see if it helps the situation.

“Don’t hide the truth and say the animal is sleeping or he ran away; it’s abstract and kids wont understand that,” said Ms. Newstadt. “Stick to the truth and avoid unknown language, explain death but leave it up to the child and what they’re asking — children can surprise us.”

A toddler is unlikely to understand death but those words should be used, she added.

“Parents could explain that medicine was given to dog and it will help him close his eyes and he will die peacefully,” said Ms. Newstadt. “Wait for them to ask “what does death mean?’ and, depending on religious beliefs, that would be a good time to talk about that.”

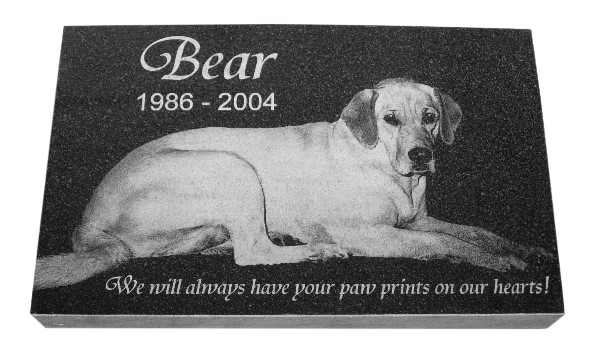

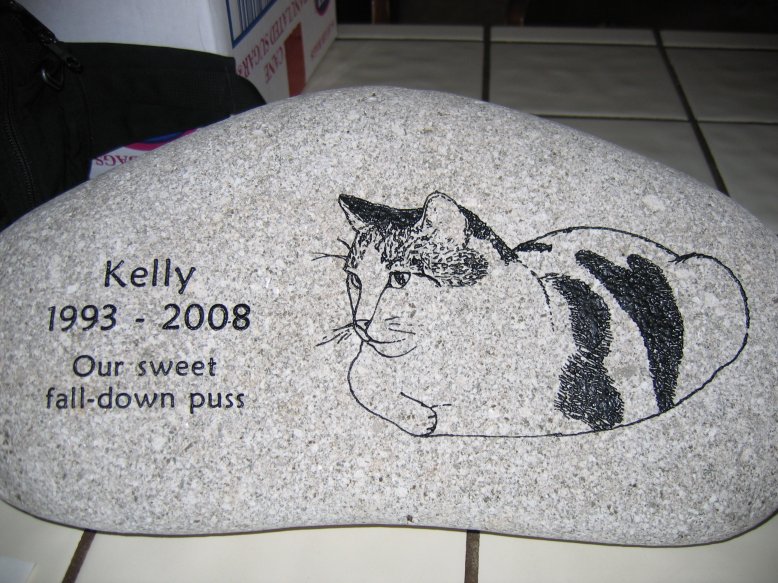

According to the local therapist, it is important to allow your child to express their feelings and deal with grief. A pet memorial would be a crucial part of the process for a child and the entire family, she said.

“Ask the child and give them choices in ways they would want to memorialize their pet and maybe each child can think of something they want to do; a burial outside, pictures in places around the house, creating a scrapbook, or a special ceremony to talk about the memories they had with their pet is important and helps them deal with grief,” she said. “This will open lines of communication which is so important when a child suffers from the death of a pet.”

According to Durham Region registered vet technician Sarah Macdonald, it is required of veterinarian clinics to dispose of a pet’s body once it passes away. A large majority of clinics also offer cremation, she said.

According to Ms. Macdonald and Ontario.ca, homeowners are permitted to bury their pets on their own property. For those living in an apartment, Ms. Macdonald recommends cremation.

The ashes can be kept in a special urn inside the pet owner’s home or be scattered in a special location for a ceremony or as part of a memorial, she said.

For those looking for more ways to memorialize their pets with keepsakes, funerals, cremation ceremonies, and more, Ms. Macdonald recommends Gateway Pet Memorial, specializing in pet aftercare throughout North America.

Parents should be focusing on positive coping strategies by modelling self-expression, letting the child know that it is OK and normal to have these feelings of sadness and that it is important to express, said Ms. Newstadt.

“Children experience grief in different ways from adults; there is no right or wrong way,” she added. “They may appear to be coping well and weeks later experience sadness. Meet the child where they’re at.”

According to Ms. Newstadt, parents shouldn’t approach the conversation until the child is expressing sadness.

“It’s OK if the child isn’t demonstrating that they’re sad, there is no right or wrong way to experience grief,” she said. “It is typical for a child to ask questions or to say they’re feeling sad and then engage in play, it’s a developmentally appropriate way of grieving.”

Complete Article HERE!