— Here’s What It’s Taught Her About Life

By Stacey Lindsay

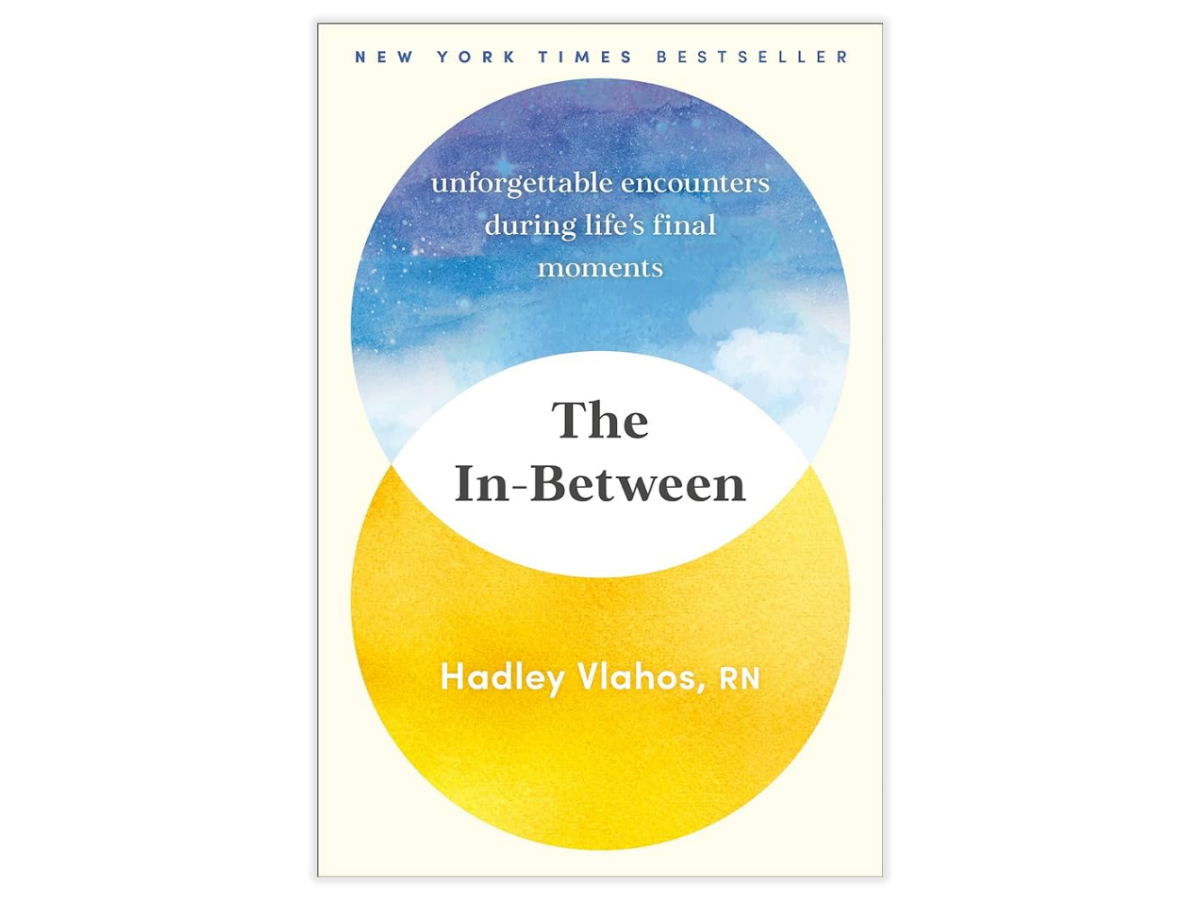

In her bestselling book The In-Between: Unforgettable Encounters during Life’s Final Moments, hospice nurse Hadley Vlahos writes the truth she sees in her job working with dying patients. “The one thing I can tell you for certain is that there are things that defy medical explanation and that in between here and whatever comes next, there is something powerful and peaceful.”

Alas, Vlahos still knows that “in between” and death are tricky topics. Death anxiety is real, she tells The Sunday Paper. But it is this angst that she hopes to dispel, both with her honest posts on social media (Vlahos has over 2 million followers on TikTok and Instagram combined) and in her book, in which she writes about all she’s witnessed and gained. As she says in a video post, “I found life again from caring for dying patients.”

Books on what those who are dying can teach us abound, and they share beautiful similarities in how we must grab the time we have and learn to embrace the beauty of passing on. Yet The In-Between is a book only Vlahos could write. In her captivating narrative, she layers between her accounts of people going to the other side, her own journey of facing poverty as a single mom, taking a chance in becoming a hospice nurse, and finding a Technicolor purpose—perhaps even more remarkable than she ever could have imagined.

I’ve been a hospice nurse for seven years now. And in the beginning, it was very hush, hush. You don’t talk about it. And I’ve noticed a huge cultural shift over the last two to three years since COVID, where people want to know. People realized how in the dark they were about what was going on, and they became hungry for knowledge. And it’s wonderful. Whenever you’re educated about something, it reduces the fear around it. I think everyone has that little bit of death anxiety, of course. Whenever we open up and talk about it, it makes it better.

You share these bone-chillingly incredible stories about things that happen to people as they are dying in hospice that, as you say, “defy medical explanation.” Many people connected with loved ones; in one story, Miss Glenda started talking to her deceased sister in the time leading up to her death. Tell us more about what you see.

We don’t learn in nursing school about people seeing deceased loved ones. So, whenever it first started happening, I thought it was a hallucination. Because that’s what I learned: People take medications, and then they hallucinate. And then I started talking to all my hospice coworkers and physicians, and I realized that they don’t believe that it is hallucinations. My first thought was maybe they’re all religious. But then I started being the one in control of my patients’ medication; I was the one who knew what they were taking and not taking. I would see the correlation between no change in medications, some patients not taking medications at all, and people with completely different religious backgrounds and diagnoses, and they were all having the exact same experience of their deceased loved ones coming to get them at the end. I started looking into it, wondering why this was happening and we don’t know why. There is no explanation as to why this happens and it is incredibly interesting to me.

There are a few different ones that happen. There is the seeing of deceased loved ones. There is also something called terminal lucidity, which is where people with dementia and Alzheimer’s will suddenly gain their memories at the end and be able to have conversations. I don’t witness it too much, but it is unbelievable to witness, and we don’t know why that happens either. The other one is what we call a surge of energy. That is where people at the end who have maybe been bed-bound for a while or have not been eating or talking much will suddenly be like, ‘I want to go into the living room and eat my ice cream and chat with my family.’ We don’t know why it happens, but it can sometimes give people a false sense of hope. And that is hard because loved ones will call me and say, ‘They’re doing so much better. I don’t even know if they need to be on hospice,’ when in reality, it usually means that they’re going to die very soon.

Going back to what we were talking about, whenever we educate people, they then know, oh, this could mean that my time is limited, and I need to enjoy this moment and take advantage of it.

This all sheds light on how we may force things on our loved ones who are dying, perhaps food or water, for instance, when they no longer need it. It is well-intentioned, but it speaks to a need for more understanding. What do you wish people who have a loved one who is dying knew?

I wish people knew that patients know that they’re dying. A lot of times, I watch this dance where someone is on hospice, or they’ve had terminal cancer for years, and no one wants to talk about it. Everyone wants to pretend that it’s not happening. What they think they’re doing is they are being kind by not saying, ‘I know you’re going to die one day,’ and not bringing up a difficult topic of conversation. But in reality, what I see with a lot of patients who confide in me is that they feel alone. They have all of these big feelings and thoughts and feel like they can’t talk to anyone about it because people change the subject. So I always tell family members, if your loved one brings it up, please talk to them and don’t try to change the subject. I know it’s uncomfortable. I know that the family members are trying to do the best thing, and they think they’re doing the right thing, but sometimes it leaves patients feeling alone.

You worked as a nurse in a traditional hospital setting before transitioning to hospice. How you speak of the hospice community paints a picture that it’s holistic and more harmonious. What things from the hospice world do you wish could be imbued in the medical world?

I have been what is called a case manager. If you’re in hospice, you have a registered nurse case manager. That means that I had patients assigned to me that were my responsibility. So, if a physician wanted something, the doctor had to come through me. If the chaplain wanted something, he had to come through me. If anyone wanted anything, they would have to come through me. I know not only what medications my patients take but also what prayers they’re saying with the chaplain and what conversations they’re having with the social workers. That kept things very cohesive.

A lot of patients tell me, and I’ve seen this from my own experiences, that it can feel like your cardiologist is telling you to do one thing and another doctor is telling you to do the opposite. No one in there’s saying ‘Okay, the cardiologist said this, let me call them.” Because so often, patients don’t know how to have the medical conversations that need to be had. There needs to be that one person. Right now, the only case managers we have in the hospital-type setting work for insurance companies, and that can be a gray area, as they’re usually on the phone and not caring for the patient and laying hands on the patient. So, I think other areas of medicine could learn from that approach, making it holistic.

You’ve said many times how positive of an experience death has been for so many of your patients. What can that teach us about life?

It can really teach us how to live a good life. Truly. I think that whenever we recognize that our life is short, and that’s such a cliche statement, but whenever we realize that, Okay, one day, I’m going to be on my deathbed. I see my patients, and I think, ‘That’s going to be me one day.’ So am I doing what I want to do every day so that when I’m in this position one day, I don’t have regrets? Or I can look back and do my life review with my own nurse and be like, ‘Yeah, I really went for it. Maybe I failed a little bit, but I really went for it. I really lived life.’ I think that that’s a really beautiful thing to be able to do.

When it comes to life wisdom, regrets, and looking back, what are some things you’ve heard from people as they pass on?

They tell me a lot! ‘Eat the cake,’ which I put in my book, is one of my favorites. I think about it all the time. But one thing that people have told me a lot, which I surmised from all of them, is that they lived for other people instead of themselves. That can mean a bunch of different things. That could be buying a new car because the person on the street has a new car. That could be choosing a career because that’s what your parents or society expected of you. Those are the regrets I’ll hear: They wish they would have just lived for themselves instead of others. Whenever I first heard ‘Don’t try to keep up with the Joneses,’ as someone said to me, I first thought the best way to live is to have no possessions and live a very low-key lifestyle. But as I started talking to more people, I realized it was more about: If you buy this house, is it because you love the house and you love coming home to this house every day? Does it make you happy? Or if you’re really into cars, does that car bring you joy? So I’ve realized that ‘Keeping Up with the Joneses’ means buying stuff for other people, not yourself.

What is the “in-between”?

It has a few different meanings. The main one is that I feel I’m with patients in between this world and whatever comes next. We get that little window of patients between worlds, and they seem to go back and forth. It’s my favorite period of time. I love being part of it.

On a more personal life side, the in-between for me was getting comfortable in the uncomfortable and being able to say, ‘Maybe I don’t have the answers, or maybe my life isn’t exactly how I want it to be, but I’m still finding happiness in this in-between phase.

Your book has been wildly successful. What did you hope people would take away as you wrote it? And what has surprised you now that it’s in so many people’s hands and ears?

I hoped that people would have less death anxiety. Whenever we turn on the TV, we see this tragedy—all the time. There was just a study that came out about how 80 percent of what we’re shown is just traumatic deaths. And I’m aware that that is not the reality for the majority of people. So, I was hoping that people would understand that you’re likely going to die in a slower way. And I think that that helps with people’s death anxiety. That was always my goal.

I was very shocked just how much people loved it. And I was very shocked at how much people related to me on a personal level. I was nervous. I quite literally wrote whatever my thought was. I put myself back in that moment in time, and whatever my thought was, whatever I was thinking, I just wrote. It was extremely honest, and I was a little bit nervous about it. I have been shocked by the messages, handwritten letters, and people just saying, ‘Thank you. I’m really glad to see someone else go through these things.’

And then how many ‘Eat the Cake’ tattoos! I think I’m up to 17 tattoos that I’ve seen. I love them so much!

Hadley Vlahos is a registered nurse specializing in hospice and pallative care. She is known as “Nurse Hadley” to her over two million followers online. Her first book, The In-Between: Unforgettable Encounters During Life’s Final Moments, is a New York Times bestseller. Learn more at nursehadley.com.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!