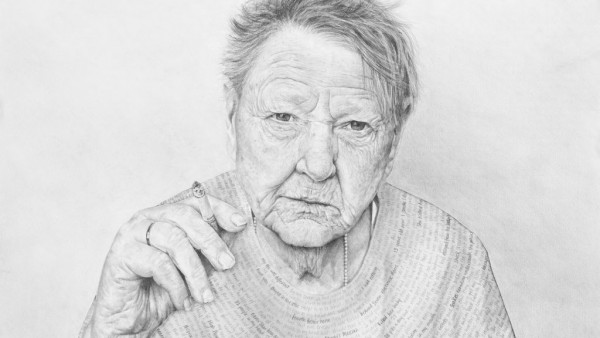

Hospice nurse Jen Moss admires the spirit of patient Jody Wooton

Jen, 41, did not set out to become a hospice nurse, but she feels compelled by a tragic past

Jody, 64, is one of a growing number choosing to die on their terms

BY ERIC ADLER

Jen Moss took to Jody Wooton from the first moment they met.

Jen, 41, the hospice nurse. Jody, her irreverent patient, all but spitting in the eyes of her doctors.

‘Refuse treatment and you won’t live two months,’ ” Jody remembers one doctor chiding her. Jody, 64 and with a wilting heart patched together with a quilt of 11 stents, glared back at him through rectangular glasses.

“Only two months? I usually get four, you know!”

Jen, whose own life has been touched by violent death in ways few have experienced, so wants to give Jody the good and peaceful death she deserves.

Jen admires her spunk, seeing behind what even Jody’s family recognizes is a sometimes cantankerous cover.

The way Jody sees it: hell if she is going to take more of that “crap,” as she puts it, from some pissant physician who felt it was his duty to pump her full of meds and IV fluids until her body bloated and her fingers swelled like blood sausage. It had happened before.

“Couldn’t wear my clothes,” Jody complains.

Three times over a decade, doctors said she might die from her bad heart. In March 2015, she actually did, but doctors jolted her back.

When she woke in recovery, oxygen and IV lines crisscrossing her body, she excoriated hospital workers.

“I said, ‘What the F are you doing?’ I had a DNR!” — a do-not-resuscitate order. But the hospital couldn’t find its copy, so the doctors brought her back to life.

After that, she was fed up.

“Wouldn’t back down for anything or anybody,” says Jody’s brother, John Kerby, 54 and a trooper with the Kansas Highway Patrol. “Everybody was a friend, unless you gave her reason not to be.”

So that was it. Call hospice, Jody told her sister. Jody was already widowed, terminally ill, no kids.

“I will be here as long as I’m supposed to be here,” she says now. “Nobody is going to tell me that I have to do this right now, or that right now.”

She will die on her terms.

“If I’m doing this,” Jody says, “I’m doing it my way.”

It’s a choice that ever more people are making in the United States. From a handful of nonprofit programs in the 1970s, hospice care has exploded to more than 6,100 programs, most of them for-profit today. Hospice now is a $15 billion a year industry.

Of the 2.6 million Americans each year who die, almost half, 1.2 million, die in hospice care. Their family members can take some semblance of peace knowing they died not alone in a hospital, but among loved ones in the place they saw as home.

Jen works at Kansas City Hospice & Palliative Care, which was one of the first hospices in the area when it opened in 1980 with two nurses and 13 patients.

Today the nonprofit employs 177 nurses, along with chaplains, social workers, counselors and nurse aides, who care for some 2,300 patients a year. There’s Jen’s “blue” team for home care, a “red” team for nursing homes, a “gold” team for both and a “carousel” team for terminally ill children.

The program is only one inside a crowded field of nearly 40 Kansas City area hospices. Elaine McIntosh, president of Kansas City Hospice, calls it “one of the most competitive areas in the country.”

Job chooses Jen

Neither Jody nor Jen anticipated the connection they’d find in hospice.

On a chilly morning in February, the nurse, just over 5 feet tall and with a tumble of shoulder-length black hair, rolls her silver Ford Fusion to a stop across the street from Jody’s home in the Overland Towers Apartments, an eight-story complex for senior citizens at 86th and Farley streets in Overland Park.

She gathers her belongings, grabs her stethoscope and checks her satchel, which contains a tablet computer with the names and medical records of Jen’s 13 patients: another woman, 64, dying of congestive heart failure; a 66-year-old man with Alzheimer’s; a father of three children, age 60, with bone cancer.

Among the patients she will see later: Al Jensen, a 90-year-old Navy veteran of the Normandy invasion who until recently has been as healthy as a war horse. His goal was to live 10 to 20 more years, but that was before doctors discovered more than a dozen cancerous tumors riddling his insides.

“Morning,” Jen says cheerily as she enters the Overland Towers lobby. A smattering of residents with canes or walkers smile and wave from their chairs.

Truth be known, as a self-described optimist and mother of three lively sons, Jen never in her wildest imaginings thought she’d be doing this job.

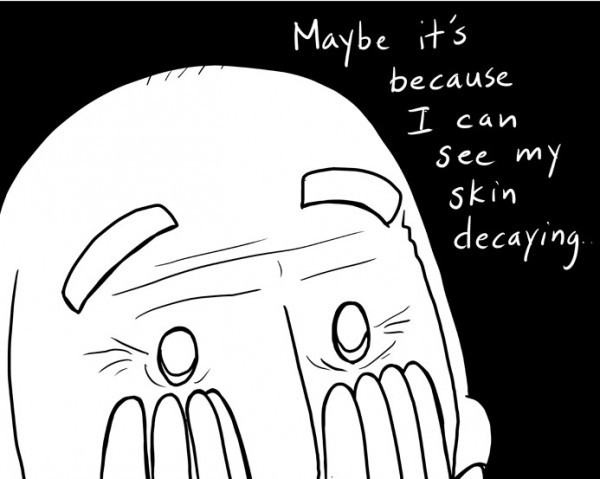

When she started her nursing career, it was in a hospital’s orthopedic/neurological unit, followed by neonatal intensive care. She moved to a dermatology practice and had a friend who’d become a hospice nurse. Jen recalled thinking, “Who in their right mind would choose to be surrounded by dying people every day?”

At Rockhurst University, one of Jen’s nursing professors spoke glowingly about it.

“My God,” Jen remembers thinking, “that sounds awful.”

But after two years with Kansas City Hospice & Palliative Care, she has come to experience the job’s grace, along with the deep, even spiritual satisfaction that accompanies her connection to patients and their families at one of the most difficult moments in their lives.

More, Jen wonders whether this is what her grandmother was talking about when she assured Jen, especially in her darkest moments, that “God has a plan for you.”

“Sometimes you don’t choose a job,” Jen says. “It chooses you.”

Who better to choose than someone like Jen, with a tragic past few could fathom?

“My sister says I should have been on the Oprah show,” she says. “My whole life has been dramatic, surrounded by death. My life has led me up to this job.”

Living around death

If divine or cosmic plans exist, Jen would argue that hers was set in motion months before she was born. That’s when her biological father, at age 23, died in a car wreck. Her mother, married at age 18, was just 19 and three months pregnant with Jen. Now she was a teenage widow.

Years later, as Jen herself was turning 19 — a year after her graduation from Park Hill High School — she also became pregnant and in 1994 had Neil, the first of her sons. Becoming a nurse had been a lifelong goal, “but college went by the wayside,” Jen says.

Instead, as a single mom, she worked for years as a waitress and bartender on the County Club Plaza, where she fell in love with Eduardo Gonzalez, a handsome dishwasher from Mexico.

They married in Las Vegas. They had a son, Frankie, in 2000. The family of four was happy.

Until, on a September night in 2002, Eduardo went out with his brother. Jen had an ill feeling.

“That night I knew. I just knew,” she says. “I’m like, ‘Don’t go. Don’t go.’ He’s saying, ‘Why not?’ ”

The call later broke the night’s silence: Come quickly to St. Luke’s Hospital. There had been a fight and, as Eduardo ran to protect his brother, a gunshot. Jen burst through the emergency room doors and was given word.

“I heard screaming,” Jen recalls. It filled her head but seemed far off. The voice was hers, echoing in her ears as she disassociated from the tragedy. “The next thing I know, I’m against the wall on the floor.”

Jen was 28, widowed with two children. Family and friends gathered around her, including her cousin, Tony Rios, who was Jen’s age, and Olivia Raya, Tony’s 26-year-old girlfriend, who was soon to graduate from Rockhurst University. It was Olivia who had been urging Jen to fulfill her dream: Go back to college. Become a nurse.

Then, three months later and days before Christmas, Jen had a dream. It was beautiful.

“I’m sleeping,” Jen says. “It’s like a white light, and we’re like spinning in a circle: me, Tony and Olivia. And they’re telling me that they’re OK, everything is going to be OK. It was just this overwhelming calm. I was like, ‘Oh my God, I have to call him.’ ”

The next morning, a call came her way.

Tony and Olivia were dead, slain in their Kansas City home in a robbery/drug deal. Olivia, who had just graduated from Rockhurst, had been writing thank-you notes when it happened.

Jen loved her wayward cousin deeply. She had been aware that he dabbled in drugs but had no idea how seriously deep it had become.

Still grieving after the murders, she entered nursing school, where she would hear the professor talk about hospice. Married again in 2009 — to Micky Moss, a Sprint engineer, and after having a third son, Everett — she thought she had something to give.

Jen knew grief and the complications of families. Having experienced violence in life, having seen how impersonal and undignified death could be, she thought maybe she could turn it into something more graceful.

Stories of intimate connections with death are hardly uncommon among those who choose to become hospice workers. Nurse Julie Griggs, 59, who trained Jen, came to hospice 12 years ago after spending 12 years treating patients in hospitals, where she thought so much of care, including death, had turned too clinically rote and impersonal.

Like Jen, colleague and social worker Crispian Paul, 37, had also experienced tragedy, the death of her 16-year-old sister in a wreck when Crispian was 12. Her mother later died of domestic violence. Crispian wanted to help others, possessing what she calls “a comfort level” with dying.

So it is with Jen.

“I do feel like because I have had a lot of loss and have lost a spouse — I don’t know exactly what all families are going through — but I know I can offer them some empathy, and some support and just” — Jen pauses before continuing — “some kindness.

“I mean, I get so much out of it as well. I meet all these families. You know, they’re trusting me with this, this such special, horrible time in their lives. I feel like I can help support them.”

Caring, not curing

At Overland Towers, the elevator carries Jen to the seventh floor. She turns right to Room 707, with the name JODY spelled out in purple, Jody’s favorite color. Black and white stickers of puppy paw prints run up and down the door.

“Jody loves animals,” Jen says.

Cats. Dogs. A ferret. Years back, Jody volunteered for a pet rescue group. Sometimes she had six or seven dogs, plus cats, before she moved to the towers.

Jen, to be sure, can’t precisely predict how much time Jody has to live.

“I’ve see her declining quite a bit in the last three months,” Jen says. “She possibly had a heart attack, a mild one, three weeks or a month ago.”

But there is no going to the hospital. That’s not how hospice works.

“I treat her pain,” Jen says.

As common as hospice has become, workers, indeed, still find it necessary to educate people on exactly how it works.

A common mistake is to link hospice care to euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide. The notion that hospice workers give patients medications to hasten their deaths is utterly wrong.

Instead, the essence of hospice is caring for patients as they move toward the end of life, in peace and with minimal pain. As the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization puts it, hospice is about “caring” for one on the journey toward death, as opposed to “curing.”

To be eligible for hospice care, a person must be judged by a physician to be terminally ill and — making the choice to no longer seek curative treatments — likely to die in the next six months. Ninety percent do. Half of hospice patients in 2014 died within two weeks.

Jody is rare. She has been on hospice for a year, which is allowed if regular medical evaluations find the patient’s health has continued to decline in a way that makes death likely, and soon.

Once someone is on hospice, Medicare, Medicaid or private health insurance picks up the tab. Hospice patients receive a host of services including regular nursing care, prescriptions for pain and comfort, a hospital bed, a wheelchair, oxygen, help with bathing, social work and chaplaincy services.

In general, there’s no rushing to an emergency room for curative care.

“Medicare won’t cover any hospitalization,” Jen says. “They won’t cover any treatments. No diagnostics. If you’re on hospice, they’re paying for hospice.”

You can change your mind. People do revoke hospice. Some even rally and improve enough to go off hospice, then come back if they again decline. Some people on hospice choose to be resuscitated, wanting to eke out every minute of life possible, even when they are terminal.

“It’s their choice. We respect it,” Jen says.

But Jody, with her DNR order, does not want that. She is not getting better. She and Jen feel lucky that the year they’ve shared has allowed them to bond.

Similarly, Suzanne Fuller, 41, has bonded with Jody as her bath aide.

One of Jody’s problems, diabetes, caused her to lose the bottom half of her left leg. Sometimes Suzanne accidentally will step on her prosthetic foot.

“Ouch!” Jody will yelp, then, “just kidding.”

Big heart, big personality, no complaints. They laugh and laugh. Jen feels the same.

“I’m really going to miss her when she goes,” Jen says.

She knocks on the apartment door and calls out.

“Jody? It’s Jen.”

No answer.

“Jody?” she repeats, her voice a bit more concerned.

Silence still. Jen turns the knob. The door, unlocked, opens.

No sound from the other side, and Jen calls once more.

“Hello?”

Monday: For her own dignity and peace, Jody prays her death will be quick, no bother to anyone.

Complete Article HERE!