Nina Riggs pens rhapsodic memoir about living with terminal cancer

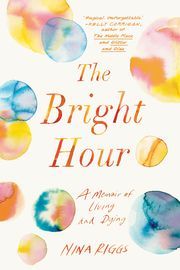

That a writer with only months to live could carve out the time and energy to chronicle her experience of terminal cancer is an impressive feat. That a writer could accomplish this with such exuberant prose as Nina Riggs does in her debut memoir, “The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying,” is revelatory. The book, birthed after Riggs’ 2016 essay, “A Couch is More Than a Couch,” which appeared in the New York Times column, Modern Love, captures vivid, dynamic moments, searing truths, bitter ironies and every delicate emotion in between.

Riggs’ great-great-great grandfather, Ralph Waldo Emerson, inspired the book’s title. “That is morning; to crease for a bright hour to be a prisoner of this, sickly body and to become as large as the World.” Riggs, who published a book of poetry in 2009 entitled “Lucky, Lucky,” was a great admirer of her literary ancestor. One particular phrase, “the universe is fluid and volatile,” in her favorite essay of his, “Circles,” helps her to wrap her mind around the parameters of her own mortality. “It allows for the idea that there are things that cannot be contained,” she writes.

Among her most referenced authors in “The Bright Hour,” though, is the 16th century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne, whose five out of six daughters, brother and best friend died prematurely. Montaigne ponders the weight of this kind of grief, and in him, Riggs finds a kind of kinship.

“I love about Montaigne that, despite roving bands of thieves and constant political upheaval, he reportedly never kept his castle guarded. He left all his doors unlocked. He acknowledged the terror that could come. But by considering it and allowing it in, he resolved to live with its presence.”

Riggs’ love of words was fervent, unbridled. She was a scrupulous linguist. The tones and the distinct sounds of syllables aroused in her a deep reflection.

“But the more I think about it, the more I’m struck by what a beautiful word it is – hospice,” she writes. “It is hushed, especially at the end. But it’s comfortable and competent sounding, too. A French word with Latin roots – very close to hospital but with so much more serenity due to those S sounds. (You see, I am growing increasingly fond of the letter S.)”

Her brief, melodic chapters, many only a page long, straddle the genres of prose and poetry, much like Emerson’s do.

Last year, Paul Kalanithi published “When Breath Becomes Air,” a memoir about living with terminal lung cancer. Kalanithi died at age 37, and like Riggs, lived for only approximately two years after his terminal diagnosis. Kalanithi’s book has been widely praised; Riggs herself deemed it “gorgeous.” “The Bright Hour” equals “Breath” in clarity, nuance and artistry. Like Kalanithi, Riggs makes acute examinations of the gradations of autonomy and agency while in treatment, and the ways in which relationships grow and reshape themselves in the face of a finite timeline.

“The Bright Hour” is also a precise study of how chronic and terminal illness affects members of the family. Early in the book, at a time when Riggs’ own cancer appears to be a relatively self-contained disease and her prognosis is good (“one small spot,” Riggs repeats like a comforting mantra), Riggs’ mother Jan is in treatment for terminal multiple myeloma. Riggs spends her time in between chemo infusions taking care of Jan. When Jan refuses further treatment, sorrow washes over Riggs. “See: She is dying,” she writes. “It is weird to write that – like I’m saying something bad about her behind her back. But it’s true. And no one knows it better than her. Eight years of cancer… My mom: my map, my Sistine Chapel, my ‘Lonely Planet,’ my beautiful ruin, my volcano.”

And it’s Riggs’ mother who, in many respects, models for her daughter the kind of perspective that Riggs later adapts when she learns that her own cancer is metastatic and incurable. “‘Dying isn’t the end of the world,’ my mother liked to joke after she was diagnosed as terminal…There are so many things that are worse than death: old grudges, a lack of self-awareness, severe constipation, no sense of humor, the grimace on your husband’s face as he empties your surgical drain into the measuring cup.”

Riggs was a wife and mother of two young sons, and as her illness progresses, she contemplates, keenly, the beauty and ferocity of the love she has for them. “When you fall in love with your kids, you fall in love forever. And that love forms the exact shape in the world of the cab of a beat-up pickup on the side of the dark highway – filled with safety and Stevie Wonder and okay-ness.” With her dear friend who is also parenting young children while living with terminal cancer, she exchanges hilarious texts about how they might monitor their children from the grave, as if “dying makes us more powerful parents than the living version of ourselves.”

Ultimately, this is Riggs’ magic. She has produced a work about dying that evokes whimsy and joy, one that sublimely affirms that the inevitability of death carries with it its own kind of light and grace. “We are breathless but we love the days,” she writes. “They are promises.”

Complete Article HERE!